- The Lawnmower – Sinister (Scott Derrickson, 2012)

Sinister has a brilliant and justifiable setup for many jumpscares to ensue, with Ethan Hawke’s character discovering a box of Super 8 films revealing a plethora of families’ grisly deaths. Many of these evil tapes are shown, showcasing drownings, hangings, and a string of other cruel fates. However, one tape, in particular, is still wedged in the back of many viewers’ minds twelve years on. The lawnmower tape displays an unknown person (later revealed to be a child!) grabbing a red lawnmower from a dark shed before mowing over grass in the pitch-black night, with the only morsel of light coming from the glow of the recording flash. Sounds of white-noise-like fuzziness play ominously over the confusing scene before the camera’s warm glow shows a person bound to the ground as the mower lashes over them with a fierce suddenness accompanied by an ear-drum bursting screech. The scene is an exercise of the classic jumpscare, brimming with brutally loud sounds and a terrifying image, yet it does not feel archetypal and expected; instead, the setup combined with the payoff is exactly how a quick jumpscare should be done.

2- Clown mask – Hell House LLC (Stephen Cognetti, 2015)

Is Hell House LLC one of the best horror films of the last decade? It might be a bold statement considering all of the fantastic films to come from this period. Yet, many a contemporary horror fan would state that Stephen Cognetti’s contributions are undeniably superb, mainly thanks to his filmography’s ability to turn every morsel of screentime into a bone-chilling expedition of great extremes. A scene in testament to this is the ‘What’re you looking at?’ scare, where a member of the haunted house comes across a demonic figure, believing it to be his friend dressed up in an eerily creepy clown suit. The true horror of the scene comes from the audience’s knowledge that this figure is not a friendly familiar but a hellish being donned in a black and white fairground suit and mask. We feel the tension bloom as the cast member comfortably stands beside his supposed friend and casually talks to it. It is not a scene where loud screams blare, or a monster leaps out. It is a simple setup with an excellent culmination to the terrifying film.

3- Camera closeup – Gonjiam: Haunted Asylum (Jung Bum-shik, 2018)

The South Korean footage horror entered screens with immediate success, coming in first at the box office on the same day of its release. Its ‘must-see’ reputation grows yearly, with the film now being one of the highest-grossing films in the country, just behind the classic A Tale of Two Sisters (2003). Gonjiam: Haunted Asylum is somewhat of a slow burn, taking its time to build trepidation before unleashing its ferocious force onto the unsuspecting viewer. There are countless incidences where you will find yourself watching the screen between peaked fingers over the eyes, but the one scene that continuously creeps up on jumpscare compilations is the ‘ultra-close up shot’. In traditional found footage fashion, the firsthand camera, in this instance, comes from the fisheye lens on a GoPro, which is mounted to the head of its user. The user in question experiences possession by a malicious spirit, turning her mouth into a menacing grim, complete with black irises and an air of pure wickedness. The intensity of the fright primarily originates from the twisted complexion that the fisheye lens provides; it’s an image straight from the uncanny valley, especially when paired with the unhuman odd squealing noise that the character makes.

4- The first appearance – I Am a Ghost (H.P. Mendoza, 2012)

I Am a Ghost remains criminally underrated despite its truly nightmarish conclusion. Describing the film can come across as a disservice. Nothing happens for the majority of the film. There are no grand acts of terror, and a monotonous routine takes precedence for the most part. However, this stagnantness is where the horror excellence shines. I Am a Ghost follows a woman from an indeterminable era in a large Victorian house, all by herself, as she goes about her daily routine of waking up, making breakfast, walking around the house, and so forth. However, something is off, a stringent atmosphere become apparent, but the force of strain is revealed ever so delicately and subtley. Yet, when the clock strikes and the realisation hits, we are met with an ungodly reign of terror in the form of a chilling creature-like demon whose appearance is a psychical shock in terms of its sheer spectacle but also an emotional jolt due to the sudden interruption into the banal, mundane tone that was at play for the majority of the film.

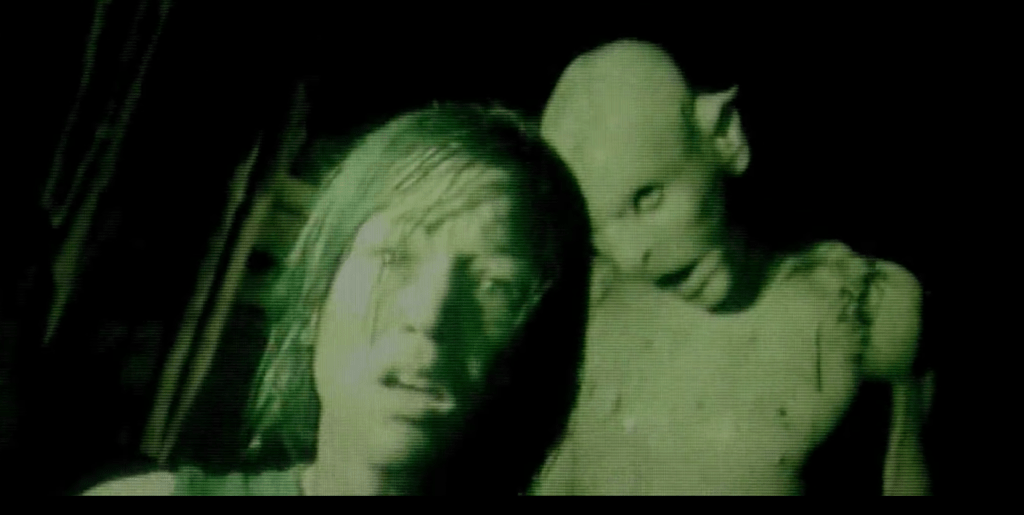

5- Night vision – The Descent (Neil Marshall, 2005)

The Descent’s unbreakable reputation still stands today due to Neil Marshall’s impeccable timing of frights, scares and gore galore. The night vision scene occurs deep under an unknown cave system amidst columns of sharp, pointed stalactites and hundreds of animal bones. Darkness prevails, and panic sets in for the spelunking group, who are becoming increasingly aware of their entrapment. Their access to night vision only provides a feeble attempt of sight, but what it does pick up is a daunting image of the humanoid creature known as a ‘Crawler’ standing over them, waiting to catch their prey. Upon discovery, all hell breaks loose, and the group’s tortuous journey to their gruesome deaths begins. It’s everything one could wish for in a jumpscare – disquieting tension, limited vision, an almighty scream and a powerful scare.

6- Car window – Smile (Parker Finn, 2022)

A common conception about contemporary horror cinema is that they are predictable with one too many jumpscares. And whilst that sentiment may ring slightly true, there are plenty of films which exercise an abundance of jumpscares with brilliance—an example of this being Smile. Parker Finn’s feature debut’s standout scene, which took many by surprise, is the ‘car window’ snippet. The jolting clip shows a woman running to a car window, only for her torso to fill the car window, and her neck to seemingly contort and hang low, pushing her twisted expression into the glass and showcasing an awfully horrid smile.

7- ‘The Mother’ – Barbarian (Zach Cregger, 2022)

The payoff from Barbarian’s ‘big’ jumpscare is all in the buildup, which takes up the majority of the first half of the film. Whilst details will be kept sparse, throughout Barbarian we are unsure as to who or what will go wrong, who to trust and when the horror will unfold. Meaning that the grand reveal of the mysterious titular creature behind all the terror is all the more effective. What also propels this particular Barbarian scare to gold status is how it changes the film’s method of horror. The likes of Smile and Sinister use quick scares to retrieve a response. Meanwhile, Barbarian and I Am a Ghost utilise a general sense of devilment to entice a reaction. Barbarian often employs atmospheric dread to create fear, making this unforeseen monstrous appearance all the more frantic.

8- I Saw Her Face – The Ring (Gore Verbinski, 2002)

Gore Verbinski’s adaption of the Japanese classic Ringu (1998) is an example of a remake done right. There are countless instances where the film takes us on a frightening ride, but there is one scene that stands out amongst them all – the infamous ‘I Saw Her Face’ extract. During a somber funeral service for a young girl hit by the tragedy of The Ring’s lore, the victim’s mother tells of her heartbreak and sudden death of her daughter. The scene is one of solemn and tenderness, mourning the sadness of a life lost, however, in an attack of complete sporadicalness the camera cuts to the girl hunched dead inside a closet, mouth gaping open, eyes drooped and bruised skin. Brutal, bold and beyond bone-chilling.

9- The Haunting of Hill House (Mike Flanagan, 2018)

Mike Flanagan is the ultimate horror connisseur, what with being a known avid horror fan, which continuously shows through his extensive filmography. Although The Haunting of Hill House is not a film but mini-series, it truly is a cinematic masterpiece. The show as a collective nails the art of a jumpscare. It features scenes of brief, sudden thwacks with booming sounds providing plenty of nerve jolting attacks to the senses. On the flip side, there is an equal amount of long, dreary, shocks that unnerve as much as they panic. Whilst there are too many scenes to pin the precise focal point, a few masterly frights include every appearance of the Bent Neck Lady and the ‘car scare’.

10- Hide and Clap – The Conjuring (James Wan, 2013)

To set the scene, a mother and child are playing the hide and clap game, which is akin to a Marco-Polo, hide and seek activity. In an attempt to locate the hider, the seeker (the mother) follows the claps, leading her to the entryway of the basement. Now in complete darkness with only a small glow lighting up her face, she waits for the next clap, only for the silence to be broken by a clap from right behind her. Loud screams and panic ensues, but the real reaction comes from the slow buildup, shivering in anticipation waiting for a clap to appear out from knowhere and cut the unbeliviably thick tension.

Want more top horror lists and reviews? Check out our blog here..