To say that The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) helped shape the horror genre as we know and love it today would be an understatement. The film essentially tore through the screen and cascaded its way into the veins of genre cinema and aided in its stellar, magnetising and polarising reputation. Although its 50th anniversary is on the horizon, its reputation as a solid classic has never been more significant.

The man behind the camera, Tobe Hooper, first conceived the idea for the film in the early seventies whilst he was working as an assistant director at the University of Texas at Austin. Enchanted by the mystery of rural isolation, darkened woods and the macabre nature of the human condition, Hooper took to sketching out film plots. His narrative would mould into shape over the years, but one focus that he kept true throughout was the aspect of real horror. One essence of storied evil came from the crimes by serial killer Ed Gein, whose reign of mutilation and murder gripped the nation since his attacks began in 1950s Wisconsin.

With a rough idea in mind, Hooper enlisted his friend and fellow film creator Kim Henkel to flesh out what would soon be a titular force in the world of horror. Upon the trials and tribulations of funding, eventually, the pair eventually produced the film for around $140,000. Due to the scope of the project and the somewhat limited budget, the film developed an all-hands-on-deck mentality where the cast and crew gave themselves to a gruelling filming schedule and journey. With a dream of developing a contentious project for the time, the relatively unknown cast was deployed to Texas where they took over a farmhouse and its land where the southern humidity reached temperatures of 43°C; keep in mind that the shooting schedule consisted of 16 hour days, 7 days a week!

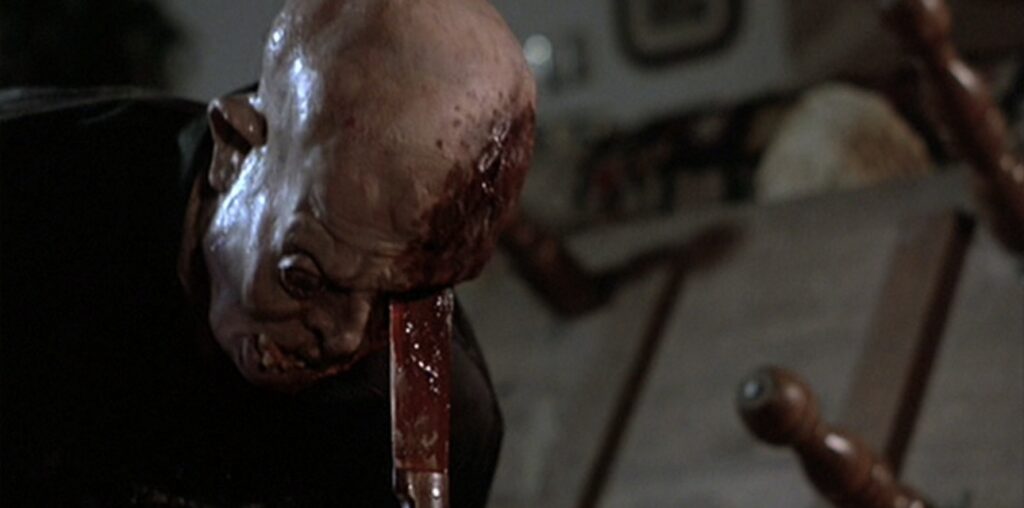

In keeping with the authenticity of it all, the various horror paraphernalia seen throughout the film such as the copious amounts of blood, bones and gore were more often than not real. The blood seen splashed up against the walls in the dreaded farmhouse was real animal blood obtained from slaughterhouses. To further aid in the genuity of it all, the crew would often traverse the local gravel ways of the area to scour and collect the decomposing remains of roadkill and dumped cattle carcases to decorate the set. As if that wasn’t enough, a few scenes refrained from practical effects and opted for unstimulated violence, for example, during one scene a tube was supposed to secrete blood, however, due to technical malfunctions the tube failed, therefore, the lead actress, Marilyn Burns, and Hooper decided it would be best to instead slice her finger open with a razor blade to achieve the desired finish.

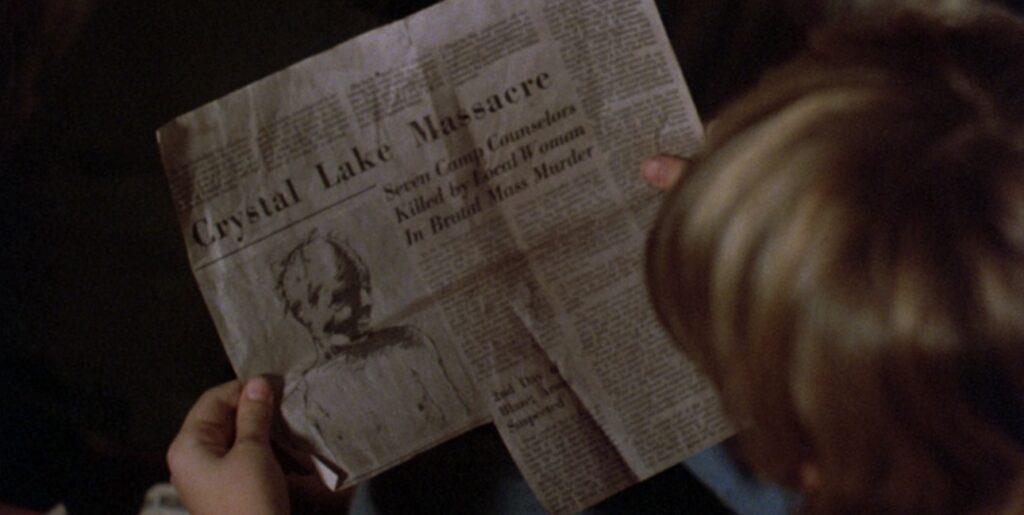

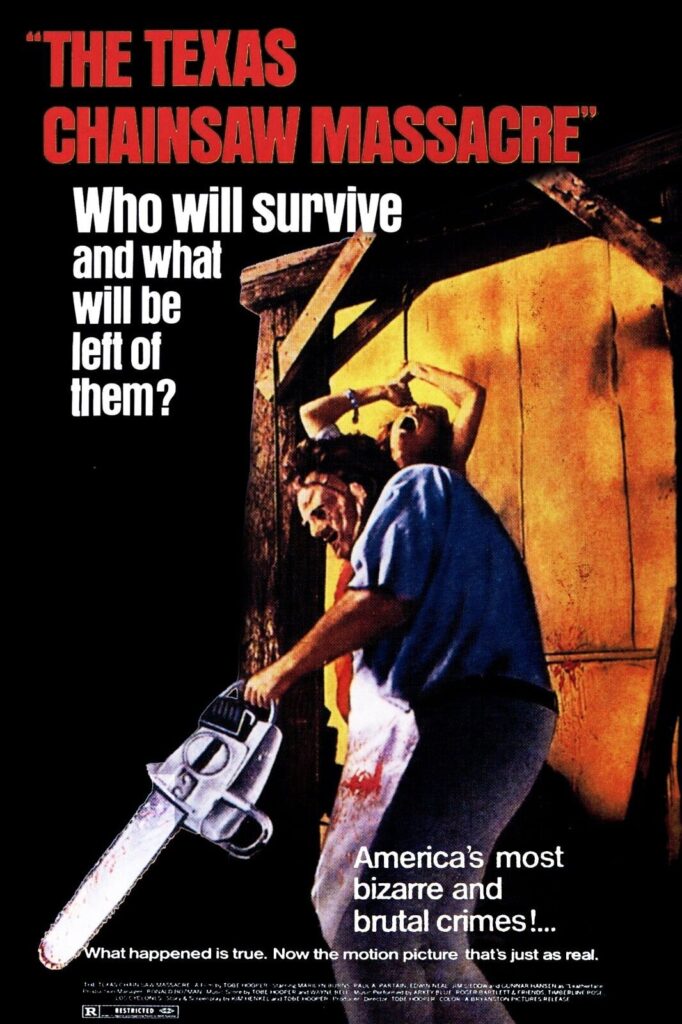

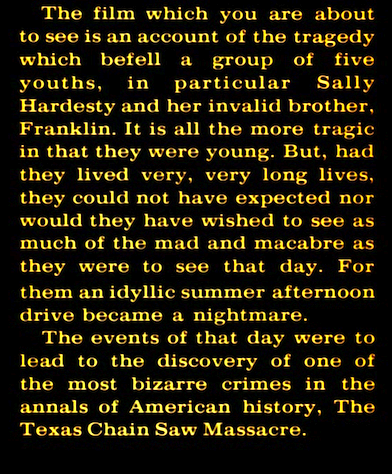

Despite all the antics and devilment that ensued onscreen, the film managed to pull in a successful run at theatres, becoming the twelfth highest-grossing film of 1974. It has been reported that a large part of the film’s success and consequential issues with censorship regimes were owed to its misconception of factuality. The opening title crawl recounts that the film is a real account, based on a ‘true story’, leading to plenty of lore regarding its origins amongst cinemagoers. Eventually, the UK’s classification board, the BBFC, banned the film, citing that it advocated for “abnormal psychology”. It was not until the early 1980s that the film was released on video, however, due to the 1984 video nasties panic, the film was once again removed from public access.

As the years rolled on and the censorship on horror loosened, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre became one of the most iconic pieces of cinema to exist. Featuring on nearly every ‘best film of all time’ list and garnering a protected and beloved status amongst all, Hooper’s once sordid feature has become a renowned classic. Many readings have circulated about the film, particularly surrounding the final girl philosophy, ‘urbanoia’ hysteria, and how the film spoke to the socio-political landscape at the time. Traversing back to the film’s title crawl – “the film you are about to see is true”, serves great significance in its diegesis. Hooper cites that the falsified warning was reminiscent of the misinformation of truth being spread to civilisation during the 1960s/1970s.

Hooper commented on how the news surrounding the Watergate scandal and the Vietnam War led to many believing whatever agenda the press wanted one to believe, with society often overlooking the hidden atrocities at the time. In a similar vein, he also took to explaining how the horror in the film was of man’s creations, not a make-believe creature, again, taking aim at humanity’s own deadliness. As it stands today, fifty years on, this undertone of commentary still remains potent, with the film’s explorations of the transgressive speaking to many of the world’s events as of now.

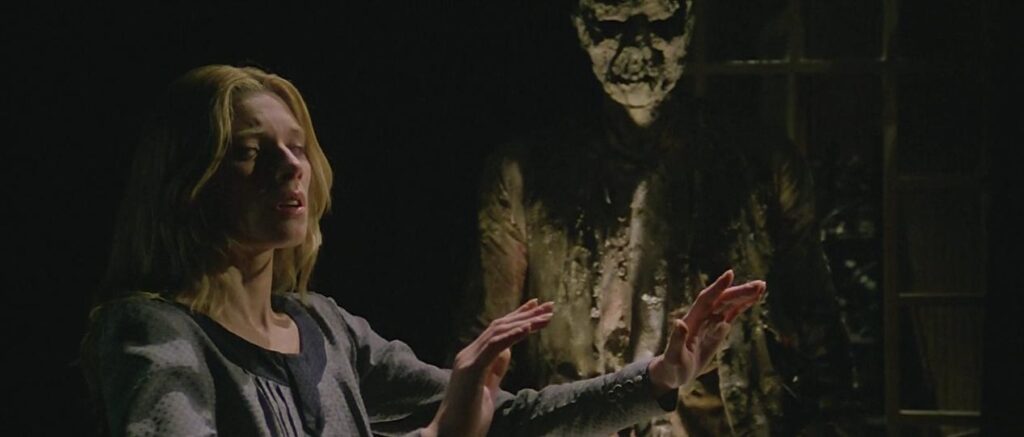

Moving onto a more creative framing, the film has served as a baseboard for the slasher genre. Many filmmakers have explicitly stated their inspirational admiration of Texas Chainsaw’, such as Rob Zombie’s Firefly trilogy. One rather obvious locus of devotion to Hooper’s classic is the film’s franchise expansion. The franchise boasts a whopping nine films, along with a successful video game spin-off, comics and books, leading to the series joining the likes of cinematic universes such as Halloween and Friday the 13th. Although some entries remain more successful than others, such as the brilliant Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986), the original remains the undefeated champion.

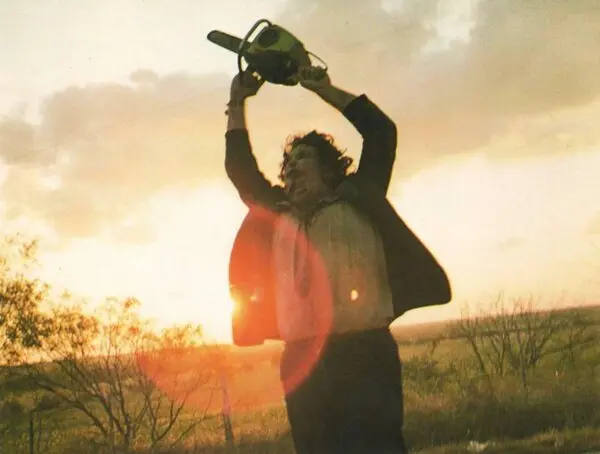

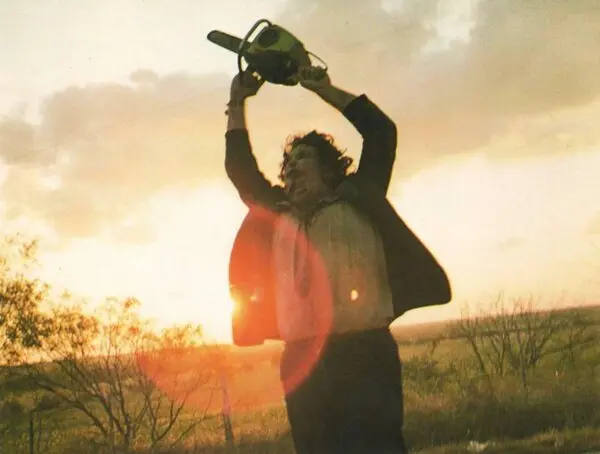

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’s contemporary reception is living proof of its indefinitely popular reception, with the film even being admitted into the Horror Hall of Fame (1990), serving as a recognised exemplary piece of filmmaking. Even aspects that seem elemental in the film still hold great traction after all this time. Think of the iconic character of Leatherface, the great force of antagonism. His character has been under the spotlight for years, with his psyche being analysed and relayed multiple times. Many see his villainy as being a product of his environment, where his actions do not necessarily come from a place of banality, but from a place of misunderstanding. Regardless of his ethos, what stands for many is how he is at the root of much of the film’s stunning aesthetic.

The film’s concluding scene shows Burn’s character, Sally, fleeing from the farmhouse, escaping on the back of a truck whilst Leatherface breaks chase with his chainsaw flinging in the air. There is something so intriguing about the sunset tones and his gruesome mask made out of flesh, along with the understanding that although Sally has escaped, Leatherface and everything he stands for still goes on thriving.