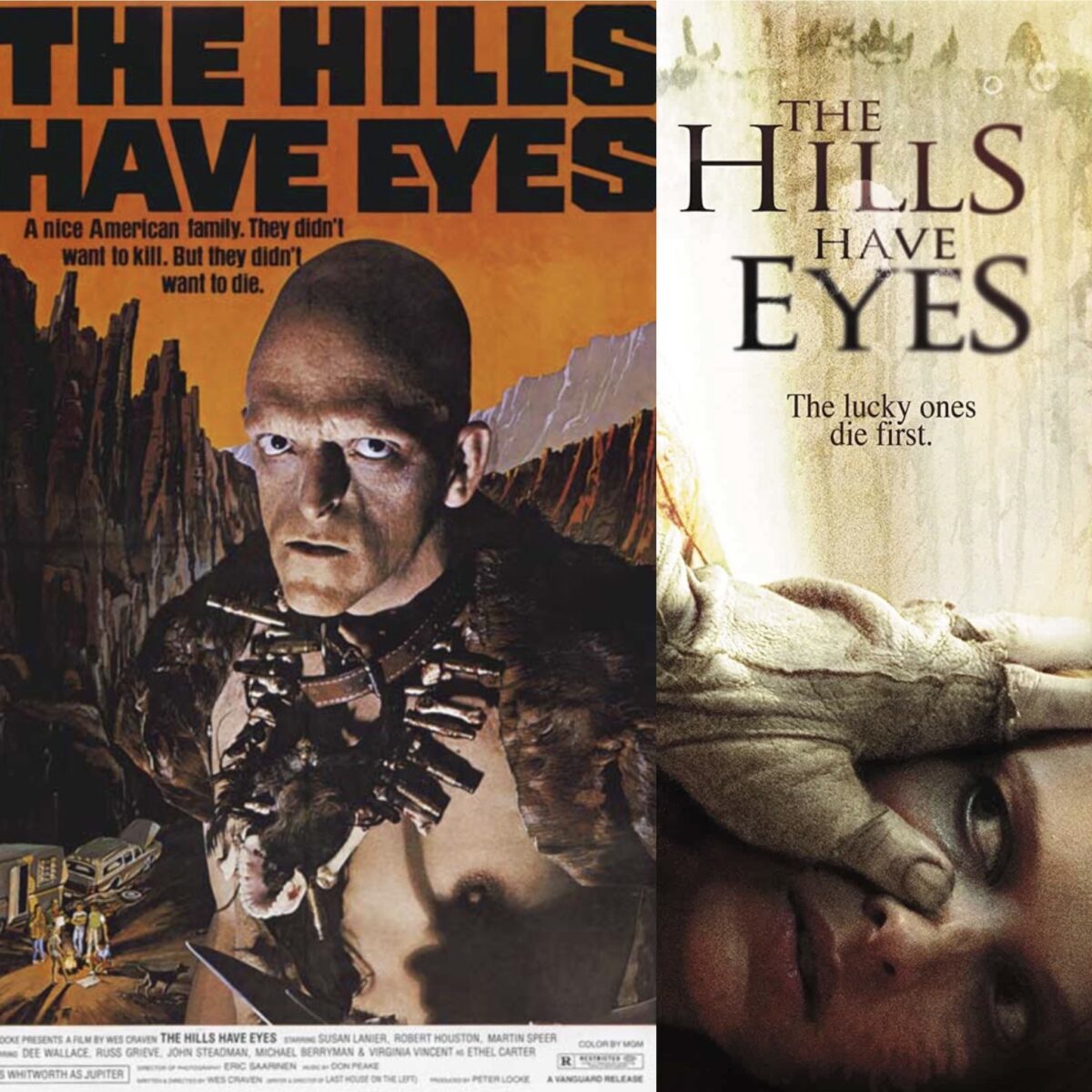

Within the current cinema climate lies a deeply debated sub section that has been seeding itself into horror for quite some time now. If you weren’t aware of it already, the interception operation of remakes has been turning every classic on its head and injecting the old with some new. Although some of the re-envisioning’s have been lacking that certain magic that allowed their predecessor to shine, many of these modern takes are rightly renowned. A prime example of this being The Hills Have Eyes.

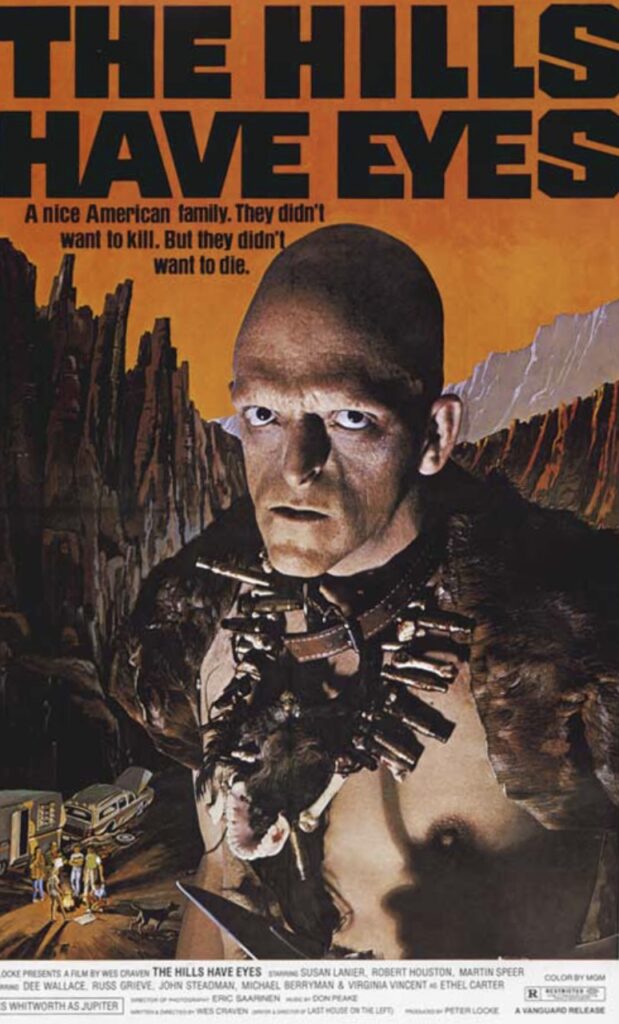

The Carter family, comprising of mother and father Bob (Russ Grieve), and Ethel (Virginia Vincent), and their three children Brenda (Susan Lanier), Bobby (Robert Houston), and Lynne (Dee Wallace), and Lynne’s Husband, Doug (Martin Speer), and their baby Katy (Brenda Marinoff) all gather for a group road trip holiday to see the sights of Los Angeles. Whilst enroute they stop in Nevada at a dingy gas station, where Fred (John Steadman) warns them to explicitly stay on the main road, but Bob knows best and detours, resulting in them being stranded after a crash. As night falls, a sickening group of teetering cannibals take advantage of the Carter’s isolation, and assault, kill, and torture several members of the family.

When we look back on exploitation cinema of the 1970s, the immediate highlights include The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974), I Spit on Your Grave (Meir Zarchi, 1978), and another entry from Craven, The Last House on the Left (1972). These films all have a soaring reputation, and understandably so. I cannot compare idolised films such as Texas Chainsaw with The Hills Have Eyes, but I can comment upon the film as having exceptionally dark tones that keep it in the horror hall of fame. The basic premise of a suburban family stranded in the blazing desert is one that is now a trope, but that current cliché once was fresh and energising, particularly when Craven used the picturesque view to juxtapose the violent imagery.

This daytime approach was eerie. There were no haunted mansions, masked killers, knife wielding escapists, or ghostly spirits, instead it was an equally discontented bunch of folk, ruthless and ready for blood. Craven’s approach of an open bright setting is relentlessly daunting, with the sandy hills seeming endless. There is no hope of someone coming by to rescue them, there is no chance of the scorching sun cooling, and even worse, there is no one there to save them if anything goes awry…

Craven took inspiration from the story of the Sawney Bean tribe who would hunt and eat their victims. Once the tribe had been arrested they were tortured, burnt and hanged by so-called ‘civilised’ vigilantes. The synchronization of the cruel acts from the deranged, and the vicious acts from the ‘normal’ provides a mischievously deep commentary on the barbarism of human nature. Relating to this is the notion of ‘urbanoia’ developed by Carol Clover.

Here the archetypes of normality are abandoned once the city is left behind, as societal rules no longer exist, including hygiene expectations, sexual boundaries, social cues, and an understanding of clear thought. The overall ecological constraints of the world are obsolete, and it’s through this that the chaos ensues in the film between the Carter’s and their depraved counterparts.

Within this division of right and wrong lies the moral question of who is worse. Yes, the cannibals committed savage acts, yet so did the Carter’s as a means of revenge. If pen was on paper both groups are morally wrong. However, Craven carefully creates a strong character arc for the primary members of the dynasty, particularly Ruby (Janus Blythe) and Pluto (Michael Berryman), which in turn creates a slight form of fan gratitude towards their presence.

Similarly to how we fight for Jason, feel sorrow for Michael, and are cheer Freddy, it can be said that we somehow root for the fighter, no matter their actions due to the reputation that has been garnered over time. Of course the acts are horrendous, but the fight between good and evil is what we’re watching the film for in the first place.

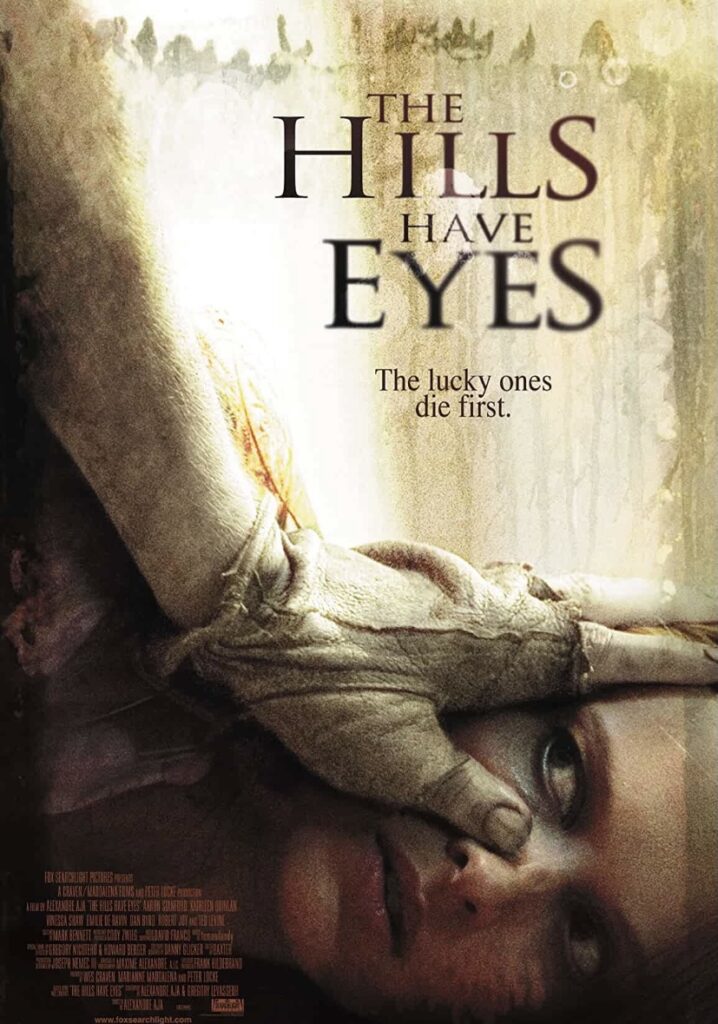

Contrasting against this is the 2006 remake that follows closely to the original but has a stronger focus on villainising the antagonists, and refining the gritty aesthetics to create a discourse drenched in blood, dripping in backstory, and focusing on the brutality of the debilitatingly vile tyrants. The homage to the original is clear, with Craven himself conjuring the idea of a remake in the first place. Upon seeing the success of other adaptations he scoured for a director with that certain aptness for creating the absurd, which soon led him to Alexandre Aja who had recently directed the French extremism horror, High Tension (2003). Craven and Aja made an outstanding duo, with dare I say it the remake surpassing the original.

This brave statement needs backing, and although the original was not cluttered with flaws it has suffered with brittle bones as time had slightly aged it. Through no fault of the film the characters on reflection do suffer slightly from genericness, and the cannibal appearances in consideration of today’s visuals were lacking a particular ferociousness. What the remake did was hone in on what makes the 1977 film such a classic, with the financial and cult success of Aja’s vision being almost entirely thanks to Craven’s original innovation. For example, the idea of a neglected family left to become beastial is terrifying, but what if their feral nature was the result of something much more contrived?

Aja sets this tone by opening the film with a scene showing scientists testing the desert ground for radiation levels as Pluto interrupts and kills them with a pickaxe. Later on it is implied that Pluto and his clan’s deformities were caused by nuclear radiation experiments performed by the government. Across the film we are graced with multiple appearances from the deformed deviants. Their monstrous appearances are greatly effective, with bulbous foreheads and skin mutations daring us to not turn away at the hideousness of it all.

Any form of connection that was established in the original is abandoned as there is literally no way that we can relate to them. And it’s not only their physical features that catalyse detest, it’s their harsh actions that go above and beyond the remorseless activity that occurred in the original. The infamous torture scene where the Carter’s are attacked in the trailer is massively amplified as we are forced to witness a jarring scene where Doug and Lynn’s baby has a weapon raised to its infant head. Lets just say that the level of inhumanity that Aja dares to show is potent.

Furthering the peaks of malevolence is the fine detail that is sharpened through Aja’s modernisation. The defined camerawork is a far cry from the shaky pans that featured heavily in Craven’s piece (albeit it added to the exploitation). Through the tuned cinematography we are treated with stunning chiaroscuro effects during the night scenes, particularly that distressing scene where Bob meets his fatal end. The vivid visuals allow for a visceral impact that lingers long after watching.

My praise for this remake is owed entirely to the original works. Aja writes a clear love letter to Craven’s stellar execution of familial chaos. It is this clear combination of stigmatising themes and gut wrenching exhibitions that casts a carefully constructed ode to what was Craven’s jumping start to his genre defining career.