The consumption of festive horror has rapidly increased over the years, with every season bringing about a brand new handful of not-so-jolly frights. And whilst many of these entries make for a perfect movie night next to a decorated tree, no other holiday horror has captured the same level of utter dread and catastrophe as Bob Clark’s Black Christmas (1974). The film chronicles the fear of a group of sorority sisters after they receive obscene phone calls from a strange man over the landline. Despite their flustered response, they soon shake the calls off. That is until a series of strange disappearances unveil the dark nature of the mysterious assailant.

Wading through the film’s expansive depths is the overarching ambiguous nature that employs the whodunit storytelling arc, along with a personalised and closed narrative that creates a strange composition of being both vague to deter predictability, with a dose of emotional intimacy to forge a bond to the protagonists. As unbalanced as this may seem, Clark wholeheartedly knows how to juggle juxtaposed themes to create a distinctive result. The phone calls act as an instigator for terror to ensue, and like a ticking time bomb, the more phone calls received, the more vulgar and abhorrent they become. In fact, the profanities uttered are said in such a gravelly and inhumane tone that it almost creates the assumption that surely the caller cannot be a real person.

Making the viciousness all the more threatening is the aforementioned personable quality. The viewer has a string of characters to follow, particularly the feisty Barb (Margot Kidder), who you cannot help but be drawn to (despite the lude humour), and then Jess (Olivia Hussey), the ‘girl next door’ who is fighting a losing battle with her forceful boyfriend, Peter (Keir Dullea).

This nuanced duplicity of Black Christmas managing to be subtle but extreme, and quiet but loud is a strong component in its successful makeup and gives credence to the film’s ability to conjure a multidimensional response. The proclivity to forecast such tonality is always a goal for filmmakers, yet it is a rather difficult aspect to achieve, making Black Christmas an achievement in all reigns.

The hedonistic gravitas that pushes the horror to the forefront is at heart connected to the laborious production where Clark meticulously worked to achieve a multifaceted study. Screenwriter Roy Moore developed the script with urban legends in mind, particularly the story surrounding a babysitter who receives repeated calls asking her to check the children. Quite eerie indeed. After a remodelling by producers where the background was changed to a university setting, the script made its way to Clark. However, he believed it to be too typical and added his own flare, including a touch of dark comedy, alterations to the dialogue, and a sense of prudence and capability to the sorority sisters. The zeitgeist of the time flourished in painting college students as being devoid of common sense, and with Clark wanting to create a piece that was more than gore-bait, he gave the final girl, Jess, a strong sensibility with difficult issues at hand.

With the formidable tension, thoroughly explored dispositions, and tenacious ploy of dread the original Black Christmas is a nirvana of yuletide terror and festive alarm. What comes with this status is an inevitable track record for a lasting legacy…and remakes.

There is no hate intended towards remakes, in fact, they can be just as, if not better than the original. When it comes to Black Christmas it can be difficult to hold it up next to such a classic. It has its strengths and a few weaknesses, but it does come from a well-intended place. Director Glen Morgan caught the attention of Dimension Films, who wanted to collaborate in recreating Clark’s 1970s hit. For Morgan, the aim from the very beginning was to recognise the significance of the original and not simply retell the already cemented work, but to re-flourish elements that stood out within a modern infrastructure. This is the primary thesis that allows Black Christmas (2006) to be a fan favourite and cult classic for many today. It understands its limitations of being a remake, yet it stands tall and works within its boundaries.

The consequence of these developments included a deeper dive into the killer at the end of the phone line, and what made him a monster. Comparisons between Rob Zombie’s Halloween (2007) and Morgan’s insistent fleshing out of the backstory have been rightfully made. It could be said that the film’s main backbone is compiled by a complex backstory that has all the ingredients to create an analogical and somewhat more frightful result. However, from a critical perspective, this is the film’s primary undoing.

In the original, the killer (now known as Billy) was not given an identity, let alone a history. The most information obtained comes from Billy’s dialogue, suggesting some sort of forbidden bond between himself and an unknown person simply referred to as Agnes. As with any popular film, over time audiences created their own folklore for characters and their possible backgrounds. The apex of Billy’s personality revolves around the perverse nature of his actions, with his dialogue and murders divulging gritty content. Morgan dives straight into the fables of Billy’s background and elaborates on who this ‘Agnes’ is and why Billy is a monster in the first place.

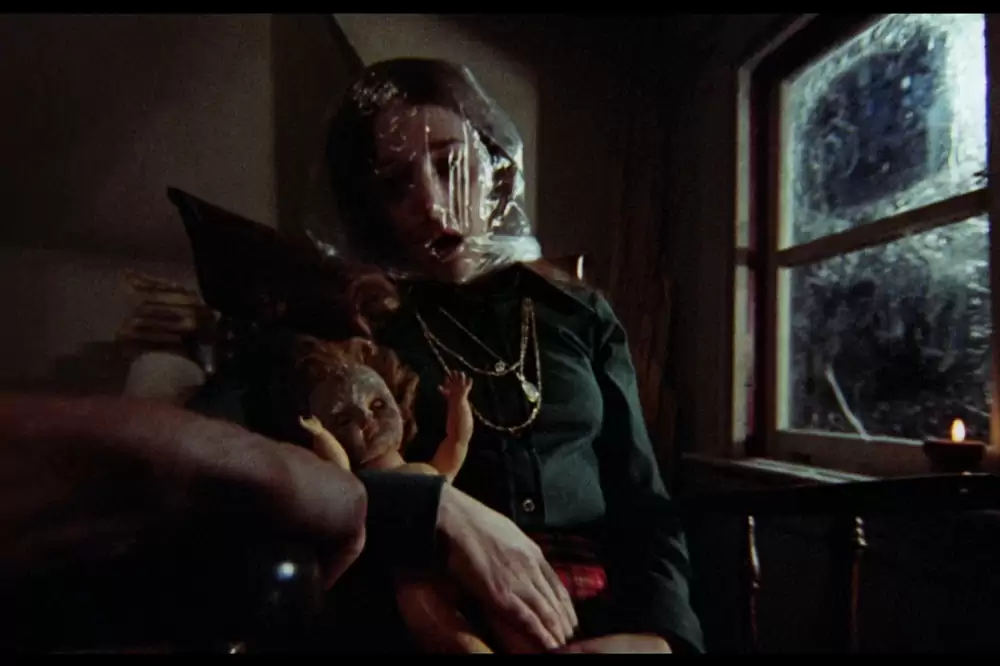

The remake establishes (in heavy flashback-based detail) that Billy’s (Robert Mann) mother, Constance (Karin Konoval), kills his father on Christmas Eve, burying the corpse in the house’s crawl space. After years pass Billy’s abuse worsens as Constance rapes him, resulting in an interbred child named Agnes (Dean Friss) and Billy later killing his mother, as well as disfiguring Agnes with a Christmas tree topper.

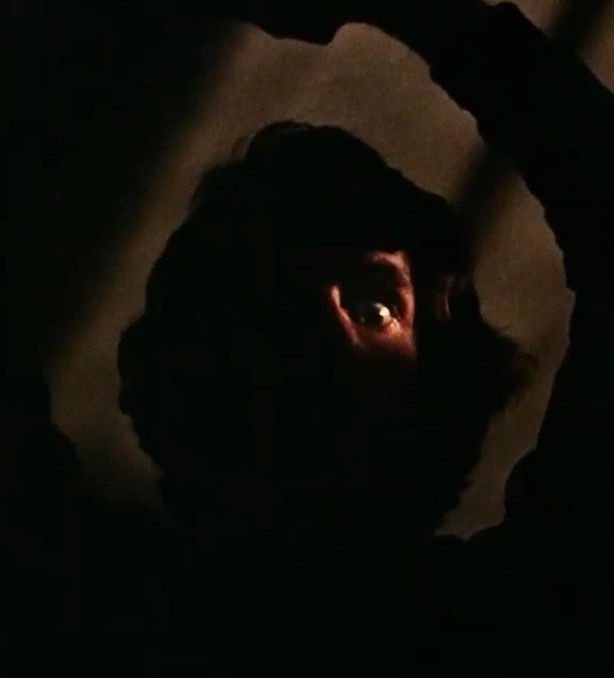

The rather dicey background is honestly quite out there for a widely released piece of cinema. Morgan’s plump retelling is impressive and makes for a ghastly and entertaining watch. Yet, the chance of suspense is completely lost amidst the packed surroundings. The original kept every little morsel of information tightly wrapped up for the entire film, even the ending is a double edged sword with the killer not being caught. There was no mask donned by Billy to create a spectacle, the absence of his presence felt in the kill scenes (with a focus on pov instead) tied in with his impenetrable demeanour, and most importantly the lack of answers made him even less human, and more beastly.

Clark’s Billy was an unstoppable force who the audience couldn’t pinpoint why he is such a sadistic person. It opened the opportunity for our minds to go absolutely berserk in working out the mystery. We were forced to project our own fears and anxieties onto Billy, making him everyone’s tailored nightmare. Whilst Morgan’s bravery is commendable and works as a standalone feat, the cruelty of Clark’s omnipotent villain is sorely missed when comparing the two films.

The remake is not solely steeped in pessimism, alternatively, there are many fantastic qualities that the film obtains. One aspect that truly amps up the fear factor and puts an impressive stamp on Black Christmas is the brutal killings. 2006 was a bloody time for horror thanks to the rise in ‘torture-porn’ works such as Saw (2004) and Hostel (2005) dominating the field with their ‘go hard or go home attitude. The fight to appease gory appetites was a rising issue, with studios resulting in painting every slasher with as much blood as possible. Black Christmas was no exception to this rule.

Arguably, with a fairly violent predecessor, the basis of every spectacle in the remake may not have been a complete shocker as some kills followed a similar path to Clark’s original splatter scenes. Still, somehow Morgan manages to take the inspiration in his stride and forge some extremely unique sequences that deserve a round of applause. The classic opening kill of Black Christmas (in both entries) involves an unlucky sorority sister being suffocated by a plastic bag, before being left to rot whilst the rest of the house goes about their merry way.

The cruel beginnings of both films are a perfect example of the difference between Clark and Morgan’s paths. Clark lengthens the scene by intercutting the full kill with scenes of Billy climbing up into the house and creeping around like a lurch (all shown from his eyes), before also showing the college tenants’ reaction to the obscene phone calls. As Billy wraps the plastic bag around Clare’s (Lynne Griffin) head, we watch as the sheet takes away any breath left, before showing her lifeless corpse in a swinging rocking chair in the attic as Billy mumbles nursery rhymes in the background.

In Morgan’s adaption, the kill occurs within a fracture of the time as Clair (Leela Savasta) is swiftly suffocated by a plastic bag and stabbed in the eye with a pen all within two minutes of the title card’s appearance. It’s a gnarly death and certainly more visually visceral, with the rapid frames taking the audience by dire surprise and showing them that this remake is not here to mess around. However, whilst this fun fire of gory madness makes for an entertaining popcorn movie, its missing that certain magic that Clark captured.

As the remake moves along, Morgan is given the chance to shine with his throwback essentialities that allow the film to have a reminiscent quality that rings back to camp 1980s slashers. The vibrant characters who take Barb’s witty euphemisms and dial them up to the max are what make the film glow with a warm, easy-going vibe that makes viewers come back to watch the gore-fest every holiday season. And whilst there were some excellent examples of eighties slashers that went above and beyond in making their characters more than kill currency, Black Christmas (2006) goes full throttle in creating over-the-top deaths that have the opportunity to introduce contemporary audiences to a slew of similarly minded films such as The Slumber Party Massacre (1982) and The House on Sorority Row (1982).

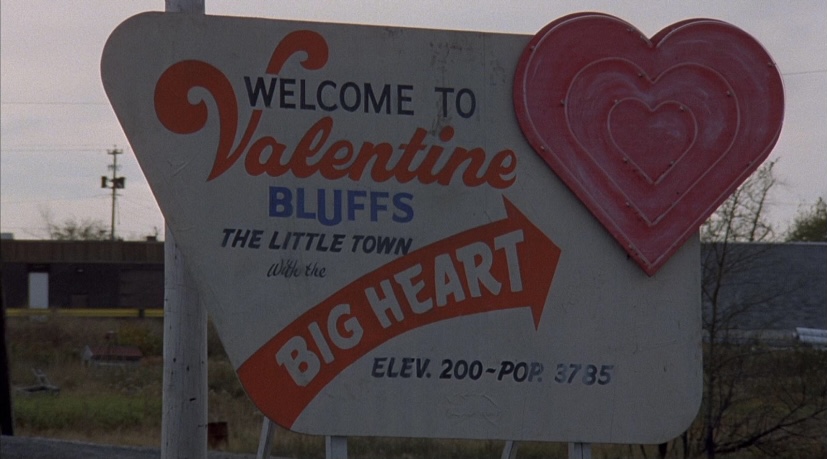

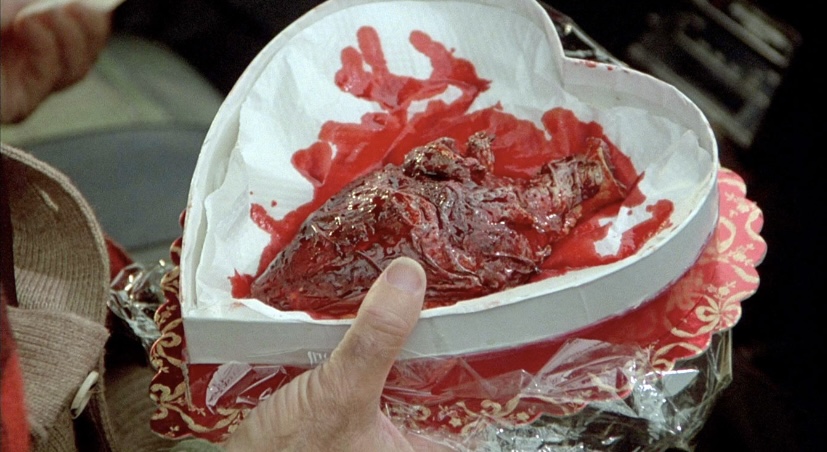

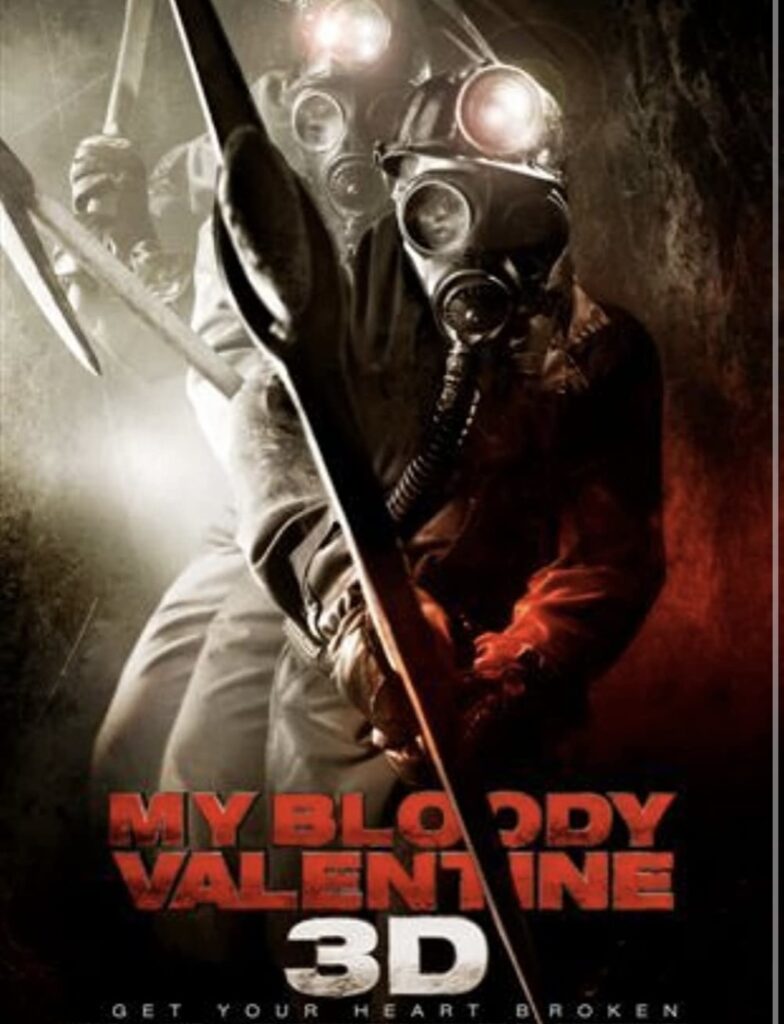

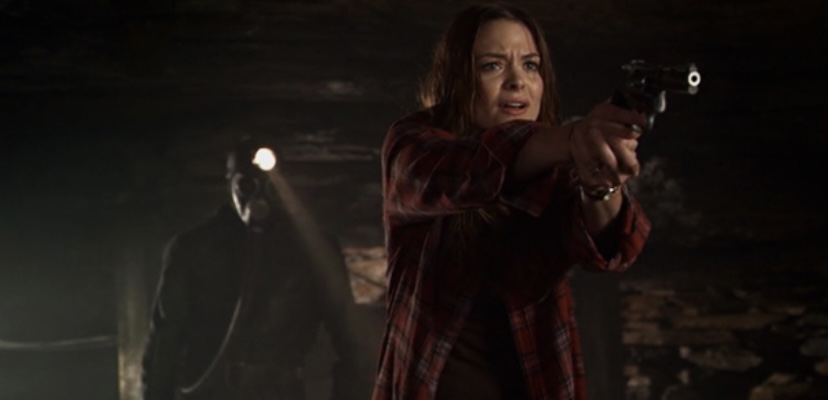

The sheer awareness that Morgan obtained throughout the filming process is an exemplary mold that other successful remakes embraced including The Hills Have Eyes (2006) and My Bloody Valentine (2009). Fashioning a remake with a spine that acknowledges its predecessor and creates a similarly-minded film but with updated aesthetics is what allows Black Christmas to be a gory Christmastime classic.

The slasher genre is forever in debt to Black Christmas and Clark’s visionary delights that wielded an archetypal sorority narrative with festive darkness to garner an everlastingly appealing horror. And with the consistent regenerative nature of horror and the churning out of remakes, Black Christmas (2006) is certainly not the worst recreation floating about. Instead, it’s a grand effort in keeping the memory of the original alive and bring forth attention to the original from audiences who might have missed out on Clark’s genre-defining staple.

Looking for more top horror lists and reviews? Check out our blog here..