1. Shaun of the Dead (Directed by Edgar Wright (2004)

The lives of aimless salesman Shaun (Simon Pegg) and his do-nothing roommate Ed (Nick Frost) are turned upside down when a zombie apocalypse hits the streets of London.

Burrowing itself as one of Britain’s most iconic films is Edgar Wright’s Shaun of the Dead, a gory zombie mashup with a classic sentiment and enough one-liners to get even stone-faced viewers a right belly laugh. The world Wright establishes from the get go is dull and monotonous, giving Shaun and Ed’s habits a paint-by-numbers feel. Even after the first zombie appearance nothing much changes, they ‘keep mum’ about the severity of the literal apocalypse. Although the humour thrives in the humdrum moments, what keeps the script fresh is the continuous trajectories that Wright throws in the mix.

The original strategy for Shaun’s zombie action plan is to go to his mum’s (Penelope Wilton), kill his snobby step-father (Bill Nighy), grab his disgruntled girlfriend Liz (Kate Ashfield), then “go to The Winchester, have a nice cold pint, and wait for all of this to blow over”- if that doesn’t ring true to the good ole’ British spirit then I don’t know what does! Overtime Shaun of the Dead has done nothing but continue to defy everyone’s expectations for both British cinema and horror, with the film even featuring in the likes of Stephen King and Quentin Tarantino’s top film’s lists, and that’s not to mention the fact that the Zombie Godfather himself George A. Romero was so impressed that he gave Wright and Pegg a cameo role in Land of the Dead (2005).

2.The Wicker Man (Directed by Robin Hardy, 1973)

Sergeant Howie (Edward Woodward) lands on the grounds of Summerisle, a small Scottish island, to investigate the disappearance of a child. Howie’s puritan ways are tested after being shocked at the Islander’s worship of pagan Celtic gods and behaving in an open frivolous manner, leading Howie to suspect that something suspicious lurks around the corner.

British folk horror has seeded its way through the roots of classic cinema with the assistance from The Unholy Trinity- Witchfinder General (1968), Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971), and The Wicker Man (1973) with the latter being a distinctly respected piece of British cinema. In the early 1970s, writer Anthony Shaffer read the novel Ritual (David Pinner), detailing the events of a Christian police officer investigating a supposed ritualistic murder in a small village. Shaffer and Robin Hardy decided to use the novel as a source to create a horror focused upon old religion to contrast against the flow of Hammer horrors being released; lead Christopher Lee was also keen on breaking away from his archetypal Hammer roles.

Over the production course, it was decided that the film would stay away from graphic violence and gore as a focus on visceral material was not the method they wanted to adopt as their fear provoker. Hardy wanted a slow burning sense of doom to gradually unveil itself within the viewer, bubbling up an atmosphere of complete dread where we know that something terrible is going to happen, but are unaware of the when and where’s. And that’s precisely what was achieved. The Wicker Man has an earthy quality, one whose quiet tension is sown from the first scene, brewing a disconcerting air of trepidation and awe over the alarming exposition and dark landscapes.

3. Eden Lake (Directed by James Watkins, 2008)

School teacher Jenny (Kelly Reilly), and her boyfriend Steve (Michael Fassbender), take a trip to a remote lake in the English countryside to spend a romantic weekend together. However, a group of delinquent teens takes their chaos a step too far, resulting in a bloody fight for survival.

Eden Lake is a rough and gritty story that uses contemporary moral panics against a muddy backdrop to expel a level of savageness that rings back to classics such as Straw Dogs (1971) and Deliverance (1972). James Watkins works at a fast pace to immediately portray Jenny and Steve to be wholesome and soppy, far from the violent criminals they’ll be running from. Whilst the plot is being thickened we are lulled into siding with the couple. During this Watkin subtly plants in elements that foreshadow their fates. For example, instead of enjoying a chill evening in a beer garden, they are surrounded by screaming kids who are way up past their bedtime, followed by angered parents slapping the littluns. It may not be much, but from the getgo, a divide is created.

During the mid to late 2000s, every news channel and paper would have a feature on rising violence amongst adolescents, raising the alarm over the knife crime epidemic, but rather than give admittance over how these problems are created due to social and generational issues, the blame would be placed on ‘hoodies’ and grime music. Filmmakers such as Watkins employ the worries of Broken Britain to create a film that makes you feel morally conflicted and worrisome. Collaborating with the commentary is the film’s genuinely frightful nature. The woods have birthed an incredible setup for horror to thrive, with the dark trees casting haunting shadows and exuding a sense of isolation. Eden Lake tactically positions us alongside Jenny and Steve in the hardened wilderness, knowing that like them we are all alone amongst the terror.

4. 28 Days Later (Directed by Danny Boyle, 2002)

A team of animal rights activists clumsily free a chimpanzee infected with the Rage virus which causes its host to go into a zombified uncontrollable rage. Four weeks later, Jim (Cillian Murphy) awakes from a coma, not knowing that civilization has come to an end. Whilst hastily discovering what’s happened he runs into a group of survivors and travels with them to a supposed safe haven.

The scene is the early 2000s, slow brooding zombies have held the spotlight for long enough, it’s time for rapid, furious, rabid zombies to rule the platform. By nature zombies are abject, their entire basis repulses, what with their drooling mouths and mangled decaying skin. When combined with the fact that the infected can climb and race, a terrifying recipe for fear is created. Danny Boyle knows how to alert our darkest anxieties, and 28 Days Later rivets and rolls to sharply hone in on that white-knuckle terror from the very first scene.

The setting avails use of the desolate grounds of the skeletal London town and dispiriting countryside as a terror provoking instrument that contrasts against the quick-paced camerawork and of course the zooming undead themselves. Adding to the intense pandemonium created in 28 Days Later is the panic-inducing score composed by John Murphy. The soundtrack continuously blasts synthesised electric drones that faintly mimic the air raid signals which would have gone off within those 28 days of the apocalypse. All of these elements, from the widescaped cinematography and booming score, to the heated performances and crazed zombies all meld together to create an unmissable showstopper.

5. The Devils (Directed by Ken Russell, 1971)

In 17th-century France, Father Grandier (Oliver Reed) attempts to protect the city of Loudun from the corruption-fueled establishment run by Cardinal Richelieu (Christopher Logue).

Ken Russell was a known agitator of the BBFC, igniting feuds amongst movie-goers over the graphic content of many of his films, and The Devils really take the honours for being not only one of his most controversial films but also a conqueror in 1970s banned British cinema. A large part of the contention resides with the themes of promiscuity painted upon a religious foreground, highlighting hierarchical abuse structures within worship and Rusell’s conscious wielding of distasteful, excess debaucheries. The Devils lewd principles take centre stage and become entirely inescapable, luckily enough the horror aspects are not covered up by the excess vulgarity. Plague-infested bodies being dumped into a limb pit, self-mutilation, and maggots sliming out of skull sockets are just some of the ghastly imagery that audiences are subjected to, thrusting the film into a dark territory that drives out a panicked and tense reaction.

6. Dog Soldiers (Directed by Neil Marshall, 2002)

A small squad of soldiers attend a mission in the Scottish highlands against a Special Air Service unit. Morning comes and they come across the unit’s sprawled apart remains, pushing the conclusion that someone or more like something is after them.

Neil Marshall forgoes a cosmopolitan setting and characters in favour of occupying the screen with rural land and pragmatic characters that waft an essence of realist brutalism throughout a fantastical storyline. Furthering the tough as nails exhibition is the apt lack of dramatics surrounding the werewolf’s existence. Marshall has stated that the werewolves purposefully do not have a lore background or curse-infused reasoning for their being.

The werewolves’ tall, gangly stature is enough to be absolutely nerve-wracking, especially when they bare their protruding fangs ready to sink into their prey’s unlucky flesh. The maximization of terror actually comes from an unexpected place, the humorous dialogue. Witty quips such as “We are now up against live, hostile targets. So, if Little Red Riding Hood should show up with a bazooka and a bad attitude, I expect you to chin the bitch” have the audience cracking up, but rather than linger in the comedy Marshall exploits the fact that our guard is down and uses the settled mood to throw in unexpected lashes of gore and frights, shaking the expectations of the audience. Dog Soldiers both mopped the floor with many creature features and created the blueprints for many werewolf films to come.

7. Kill List (Directed by Ben Wheatley, 2011)

Jay (Neil Maskell) and Gal (Michael Smiley) served together in the forces, creating a strong bond. Eight months have passed since they left an unspecified disastrous assignment, leaving Jay mentally scarred, making him unable to work. After an argument between Jay and his wife Shel (MyAnna Buring) over money worries he joins Gal in a contracted job to kill a list of people.

Ben Wheatley over the years has created some true standout British horror’s including Sightseers (2012) and A Field in England (2013), and most recently In the Earth (2021). Kill List unveils Wheatley’s naturalistic filmmaking methods in a remarkably raw manner that inflames a deep level of disturbance amongst the viewer, guaranteeing a hold over them for long after watching. Joining his fervent displays of provocation are the award worthy performances from Michael Smiley, MyAnna Buring, and Neil Maskell who all bring such ferocity and realness to their characters that it’s nearly impossible to tell that they’re actors and not the actual people they are portraying.

Kill List somehow goes both full throttle and gentle within its storytelling, with the subtle elements of something darker lurking amidst the surface, whilst also pushing frenzied chaos into the frame. This perplexing balance is even more advanced by the unpredictability of Jay and Gal’s actions, pronouncing the ambiguous nature of events and the slight art-house style that Wheatley adopts.

8. Prevenge (Directed by Alice Lowe, 2016)

Pregnant widow Ruth (Alice Lowe) loses her partner in an unfortunate climbing accident, leaving her alone. Shortly after, she begins to hear her baby talking, convincing Ruth to exact revenge on anyone involved in his death.

Alice Lowe’s directorial debut is an absolute shocker of a film. Prevenge is literal proof that budget constraints and the brackets of independent cinema are not blockades in creating a potent piece as Lowe hatches an audaciously somber and fruitfully macabre vision of a woman unhinged. There is not a single moment where we don’t align with Ruth. We have to listen to her and follow her every step, encouraging us to see the world through her damned perspective.

This creates an off-kilter atmosphere that fashions a normal-looking world, but with a surreal and untrustworthy ambiance, similar to British TV shows such as Green Wing and The IT Crowd. Prevenge is entirely impressive as it is, but what pushes the film’s intrinsic likeability even further into the atmosphere is the personable energy that the film emits. Lowe wrote, directed, and stars in this one-woman show, all whilst she was actually pregnant in real life. The level of dedication and the film’s success has to be owed entirely to her.

9. The Ritual (Directed by David Bruckner, 2017)

A tragedy strikes in a group of friends, leaving the bond disabonded. To rekindle their friendship the four of them set out on a hike through the rural Scandinavian wilderness, however, when a wrong turn ends them into ominous land, they must fight for survival.

The Ritual remains efficient, rich, and menacing– heeding onto the complexities of trauma and the threat of expelling one’s grief inwards, rather than seeking the comfort of shared loss. Boasting The Ritual’s emotional rhythm is David Bruckner’s ability to take elements of the source material (Adam Nevill’s 2011 novel of the same name) and manifest a story that alludes to Nevill’s rural atmospheric strengths, but with a surreal edge that transcends the barriers between the mind and the psychical body.

Due to this constant escalation of illusory texturization, the viewer can never decipher what the fates of the four will be. Immediately, when an isolated forest setting is disclosed an air of the ‘other’ forebodes the script, with many recalling the likes of The Blair Witch Project (1999) or The VVitch (2015) as an archetypal framework for The Ritual to base itself around. However, Bruckner dismisses the urge to be predictable or imitate previous works, opting for unfamiliar occurrences that have you questioning whether the sinister happenings are held within the fragile group’s mind or if something very real and very evil is actually at play.

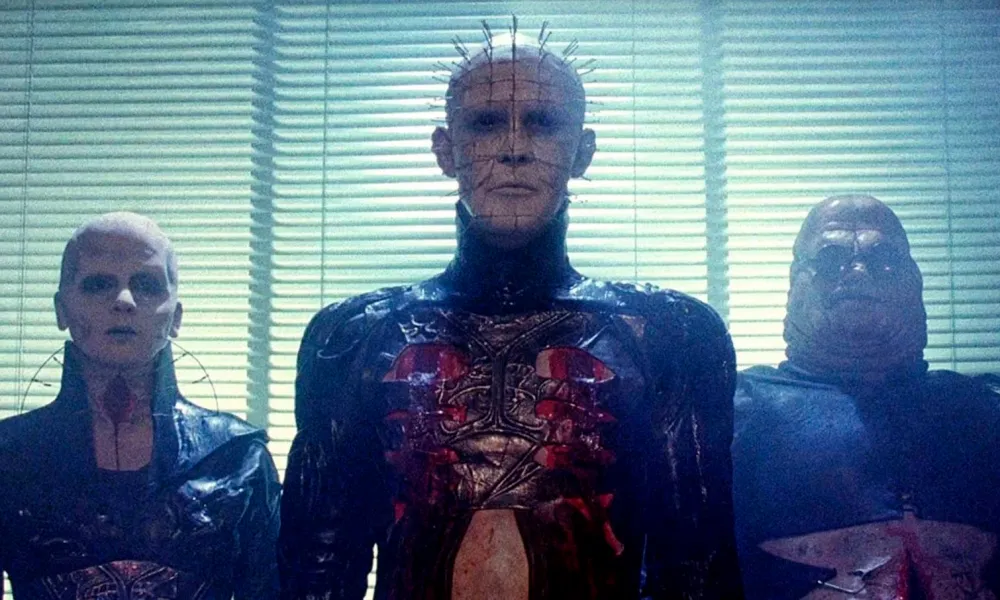

10. Hellraiser ( Directed by Clive Barker, 1987)

Frank Cotton (Sean Chapman) opens a portal to hell after solving a puzzle box, unleashing sadomasochistic beings called Cenobites, led by their leader Pinhead (Doug Bradley) who tears Frank’s body to shreds. Frank’s brother Larry (Andrew Robinson) and his wife Julia (Clare Higgins) have a strained relationship, which led to Julia having a secret affair with Frank before his death. To rekindle their estranged relationship the pair move into Frank’s old house, where a skinless Frank is accidentally resurrected, who convinces Julia to lure men back to the house for him to drain.

Director Clive Barker originally was a writer, having written the screenplays for Underworld (1985) and Rawhead Rex (1986), however, he was rather unhappy with the final execution of his developed work, leading him to direct the film adaptation of his novella The Hellbound Heart (1986). Immediately, Barker knew that he wanted to create a piece dosed in creative eccentricity and a horror betrothed to the atmosphere and cutting edge originality. Considering the fact that the film developed into an entire franchise, it’s assured that Barker’s goal of a successful adaptation was achieved.

Hellraiser’s moral compass is enriched with a dreamlike quality, resulting in dark sequences of death and destruction, and whilst the overall effect is beyond alluring, the primary source of the film’s seduction is due to the cruel unearthly creatures donning sharp exteriors and bondage-like clothing. The genealogy of the Cenobites has been diagnosed as ‘religious based’, with them deriving from a religious sect in the underworld known as the ‘Order of the Gash’ where their evolution has made them unable to differentiate pleasure and pain. Pinhead and his followers’ existence transport the film into a higher level of transgressiveness, allowing for the viewer to become blinded and lost within the utter absurd nature of Barker’s vision.

Looking for more top horror lists and reviews? Check out our blog here..