Dead Northern takes a look at the big horror film anniversaries of 2023, which films will be on on your re-watch list?

1- Night of the Living Dead (Directed by George A. Romero, 1968) – 55th Anniversary

It can easily be said that without Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, the well-exercised zombie era would not be the same as it is today. This socially conscious story ignited a spark for the genre that would inspire many influential future filmmakers, including Edgar Wright and James Gunn. Romero’s classic will be celebrating its 55th birthday this year. Despite the time that had passed, this zombie extravaganza very much lives on to this day, with the film offering key paraphernalia that is paramount in any modern zombie feature.

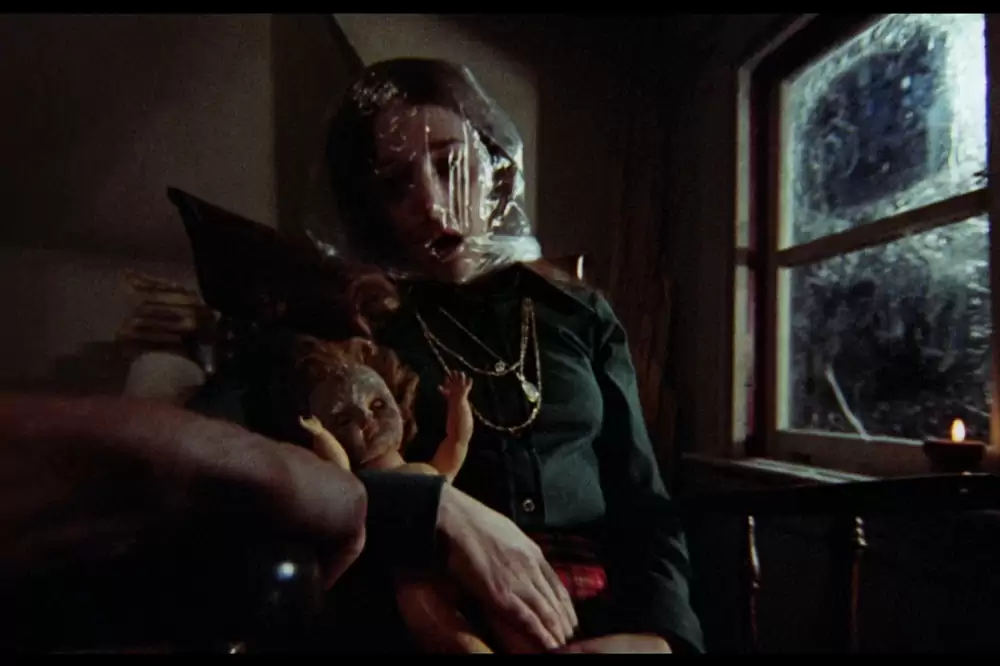

2- The Wicker Man (Directed by Robin Hardy, 1973) – 50th Anniversary

The Wicker Man belongs to the Unholy Trinity of folk horror, along with Witchfinder General (1968) and The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) depicting rural picturesque scenes amongst utterly sinister crowds. The Wicker Man has captivated audiences for 50 years now. Not that this figure is easily believed considering how timeless Hardy’s countryside horror is. Perhaps it’s the performances by Edward Woodward, Christopher Lee, and Britt Ekland that make The Wicker Man the iconic film that it is. Or maybe it’s the endless displays of brooding tensions that culminate in an unforgettable finale that keep the film’s acclaimed flame lit. Either way, The Wicker Man is far from being forgotten, and it’s highly doubtful that it ever will be.

3- The Exorcist (Directed by William Friedkin, 1973) – 50th Anniversary

The Exorcist is one of the most colloquially known horror films across the globe and one of the few frightening features that garnered admiration from the Academy Awards. Friedkin’s tale of possession, demons and a genre-defining depiction of evils have granted The Exorcist a beloved place within cinema. However, this firm favourite was not without its controversy. During its initial release, there had been countless reports of fainting and nausea, ensuring the film’s banning in the UK for 11 years.

4- Sleepaway Camp (Directed by Robert Hiltzik, 1983) – 40th Anniversary.

Summer slashers are known for their camp (both figurative and literal) splatter-fests, with films such as Sleepaway Camp dominating this bloody, sunny, and very much ‘forward’ subgenre of horror. Sleepaway Camp delivers an impeccably entertaining storyline of a whodunit amidst a summer campsite, with plenty of extremely gnarly kills featuring along the way. However, if there is one thing that makes this 40-year-old film a classic, it is the iconic ending that will leave your jaw on the floor for a very, very long time.

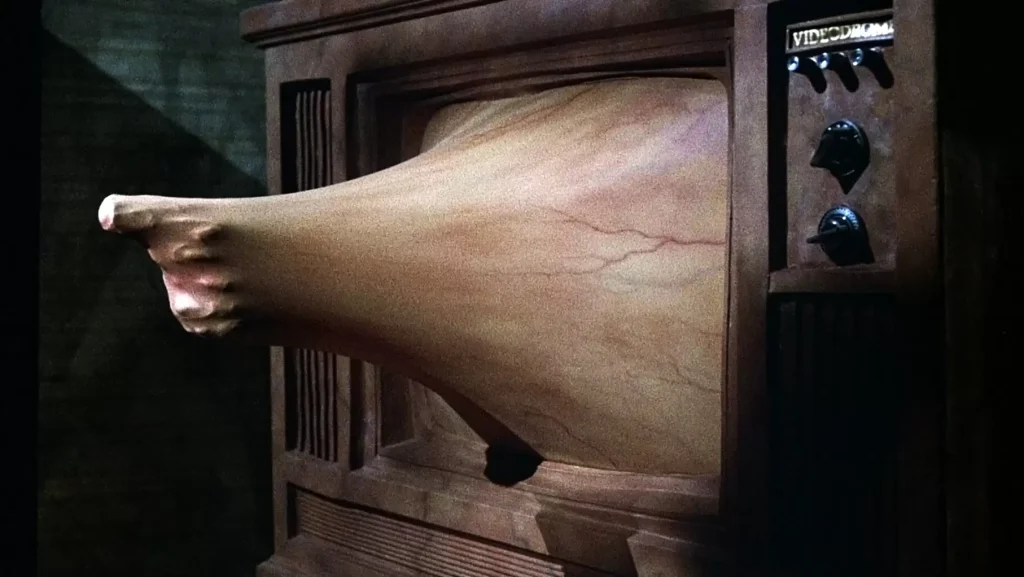

5- Videodrome (Directed by David Cronenberg, 1983) – 40th Anniversary

If there is one thing Cronenberg is known for, it’s his exuberantly horrifying filmography that refuses to shy the camera away, instead directing the frame to be as visceral and infringing as possible. An excellent example of a pure Cronenberg gem that has stood the test of time (for 40 years now) is Videodrome, which is very much a body horror through to the bone. Working alongside the icky displays of gratuitous practical effects is the science fiction plot that transports the viewer into another dimension where morals are tested and the terrifying illusions of surreality are left to run riot.

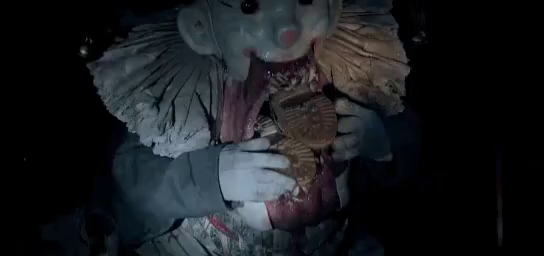

6- Killer Klowns from Outer Space (Directed by Stephen Chiodo, 1988) – 35th Anniversary

On paper, the story of extraterrestrial creatures with clown-like appearances invading a small town should not work. However, there is something so hilarious and entertaining about watching alien clowns wielding popcorn guns, going absolutely berzerk on screen. Killer Klowns rivets in the absurd, which is wholeheartedly aided by the impressive practical effects that are an absolute testament to the creativity seen within 1980s horror.

7- Ringu (Directed by Hideo Nakata, 1998) – 25th Anniversary

Ringu is responsible for the nightmares of pretty much every audience member ever since its release 25 years ago. This timeless classic belongs to the long line of technology-based terrors, which is seeing a resurgence in the current horror domain. Ringu revels in the brooding terror of slow-burn horror that takes its time in building up to a horrifying conclusion, as well as introducing one of the genre’s most chilling creatures to ever meet the screen.

8- House of 1000 Corpses (Directed by Rob Zombie, 2003) – 20th Anniversary

Rob Zombie has garnered a slightly unbalanced reputation in the horror scene, with many believing his music to be better than his filmography. However, one film from his wide selection that many can agree on being an utter bonanza of cruel fun is House of 1000 Corpses. Not only is this the feature where Captain Spaudling (Sid Haig) made his mark, but it is also where Zombie showed off his extravagant style, with the film revelling in grindhouse cinema aesthetics. This now 20-year-old film is still as hyped today as it was upon its initial release, with its fanbase securing the film as a cult classic.

9- Wrong Turn (Directed by Rob Schmidt, 2003) – 20th Anniversary

During the early 2000s, a ‘new-ish’ type of horror film dominated the genre – a neo-slasher/ cabin in the woods-esque style of feature. It is difficult to determine a definitive answer, but many will refer to these films simply as the ‘early 2000s’. A Kickstarter and iconic entry into this market was Wrong Turn, which reaches its 20th anniversary this year. Wrong Turn thrives in the sheer gravitas of the Appalachian Mountains to display gruesome scenes of cannibalism, dismemberments, and the usual graphic debaucheries seen in teen horror.

10- Martyrs (Directed by Pascal Laugier, 2008) – 15th Anniversary

Many only watch Martyrs once as this gritty gem exudes such graphic levels of torture and violence that most deem it ‘sick and twisted’. This mainstream-extreme horror is a significant player within the New French Extremity paradigm that aims to shock and startle every step along the way. As Martyrs reaches its 15th year of disturbing audiences, its connotations remain stringent, with the film’s visceral displays of exploitations aiming to comment upon the wider discourse of immortality and pain.

Looking for more top horror lists and reviews? Check out our blog here..