An individual’s predisposition to fear is mainly connected to sound. The sudden appearance of a horror film’s threat, whether it’s a demonic creature or a knife-wielding boogeyman, their presence is always going to stir a reaction. However, it’s the audio cues that first unleash the terror and sheer panic amongst the viewer. Before Freddy Kruger makes an appearance in his victim’s dreams the faint scratching sounds of his bladed fingers arise to our attention, followed by the recurring twisted nursery rhyme of “One, Two, Freddy’s Coming For You”; the basis of reaction can all be traced back to the power of music within the film.

The 1990s were a time when horror films thrived in maximalism, ensuring that no theatrical stone was left unturned. The costumes were always exaggerative of the storyline, the background and setting were beyond dramatic, and the music was crucial in setting the tone, with an emphasis on curating a soundtrack that would be as impactful as the dynamic seen on screen.

The character of Dracula has gone through leaps and bounds of representations. The Count has been parodied and trivialized (e.g. The Monster Squad [1987] and Waxwork [1988]), and he’s also been made darker and almost feral (e.g. Dracula [1931]). Out of the countless adaptions, one film that is timelessly recalled is Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992). Coppola eroticises and sensualises the entire plot by granting a god-like capacity to Dracula where his power transcends beyond blood-sucking, instead his grandness is all-encompassing to the film’s entire environment as if Dracula surpasses the barrier of the screen and has a hold on the viewer. The deliberate hazing is accented by composer Wojciech Kilar’s enigmatic score that fuses large orchestral structures to be both melodically gentle but still ostentatious and lord-like as if the music was formulated by an immortal being, Dracula himself, a character both charming and deadly.

The boastful score takes over the screen and demands nothing but full attention. In what can be considered a bold move by creating a dominating score, a sense of might is pushed towards the horror movie soundtrack, allowing for future films to spiritually feed from Coppola’s and Kilar’s forcefulness in fashioning powerful music for further films to come.

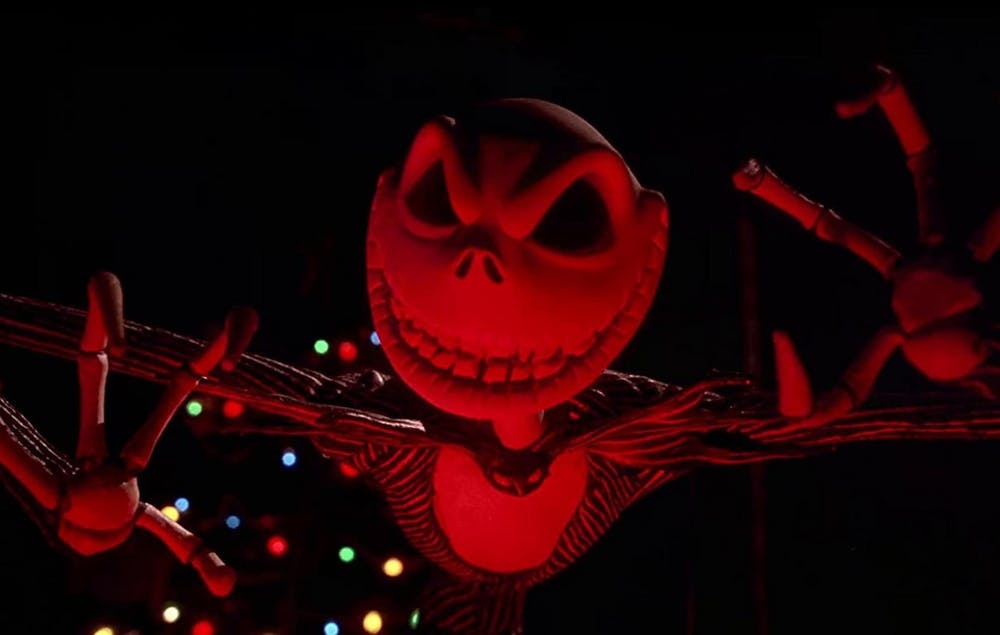

Horror as a subject can be pliable, what works for some might not work for others, however, one factor that runs throughout is the means to jolt a fright, whether that be a playful fright or a deeply souring fear is totally individualised. As the early 1990s were shaping there was an influx in ‘family horror’, films where mature audiences would feel nostalgia for their discovery days of the genre, and younger viewers would be excited to be introduced to the world of horror. Films such as Hocus Pocus (1993) and The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) saw phenomenal amounts of success across the board that still lasts to this day. Both of these films’ signature relies heavily upon the music featured. Hocus Pocus saw Bette Midler performing the Halloween classic “I Put a Spell on You” (Jalacy “Screamin’ Jay” Hawkins), which remains a spooky season staple for many. Alongside Hocus Pocus was Danny Elfman’s composition for The Nightmare Before Christmas which was awarded a Golden Globe for Best Original Score (1993) and also featured on the US Billboard charts at No. 64.

Skipping back a few years, no matter the genre cinema was thriving on big powerful movie ballads seen in the likes of Dirty Dancing (1986), Mannequin (1987), and The Bodyguard (1992). Amidst all these love songs came a rising popularity for creating movies that revolved around its sound. That isn’t to say that other cinematic elements were being surpassed, it just meant that a strong focus was also placed upon the soundtrack.

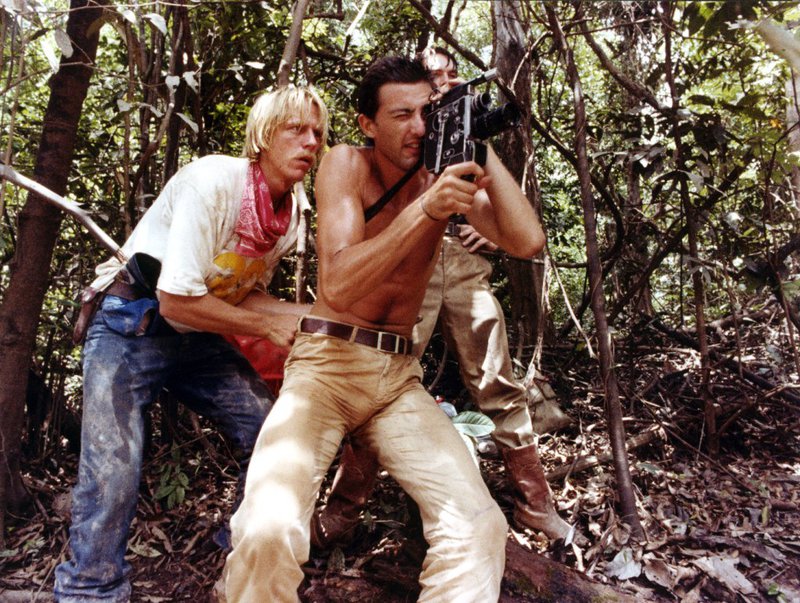

Quentin Tarintino is the perfect example of a filmmaker who uses music as a character. And when it came to his and director Robert Rodriguez’s From Dusk Till Dawn (1996), the music played one of the largest roles in the film. The irreverently charged horror is known for its chaotic characters, purposefully sleazy setting, plasmic-coloured green blood and gore, and a killer soundtrack. The dark southern score is laden with rock and blues anthems that keep the film from seeming like a peep show. The range of musical numbers features bands including ZZ Top, Tito & Tarantula, and The Mavericks. But the most quintessential tune that is synonymous with the film is “After Dark” (Tito & Tarantula), also known as the song that plays during Santanico Pandemonium’s (Salma Hayek) dance scene with an Albino Python. After Dark encapsulates the film’s entire ambiance, where the moody tones are spiked with velvety vocals and deadly lyrics that tell the story of forbidden wants and bumps in the night.

From Dusk Till Dawn is so engrained with the idea of music that even the scenes themselves are heavily based on the importance of music as a filmmaking tool. Particularly during the scene where the on-stage band (also played by Tito & Tarantula) start using a human torso as a guitar during a mass brawl at the infamous bar ‘The Titty Twister’.

Mary Harron’s American Psycho (2000) helped redefine and recontextualize the use of music in horror in the early 2000s. The film follows Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale), a murderous city swindler who has an odd penchant for music, especially whilst he is committing his deadly deeds. Artists including David Bowie, The Cure, Phil Collins, and New Order amongst many others appear on the bold and ambitious soundtrack that to this day is still used as a cultural reference. The film toys with the omnipotent power of Bateman who somehow carries out wildly violent acts in an open manner without much of a guise, with the film’s most fluorescent and upbeat songs (including Huey Lewis and the News’s “Hip To Be Square”) playing over his psychopathic killing/monologue scenes. To nicely meld the theme of desensitisation into the plot, the pop and New Wave music is strategically and continuously peppered throughout the film, making the surrealness of his dark actions being committed in a well-lit and mainly open environment seem even more dreamlike.

A couple of years down the line from American Psycho was 28 Days Later (2002), a rattling zombie movie that dials up the bloodcurdling terror to a ten from the very first scene. Director Danny Boyle leaves no room for air as the lightning-fast flesh-eaters are constantly on the hunt, and always capture their prey with ease. To go with such a heart-pounding, exhilarating narrative is the post-rock soundtrack that also combines orchestral swells to fill in the gaps. 28 Days Later’s setting ranges from a desolate London town to empty motorways and army barracks abandoned thanks to the ‘rage virus’ sweeping the country. The silence and stillness of the apocalyptic landscape are filled by the loud and ferocious songs composed by John Murphy consisting of electric guitars and bleak, depressive droning sounds, particularly “In the House, In a Heartbeat” which begins with deadly slow riffs before erupting into a stirring melody.

Although the following trend has been around for a while, it wasn’t until Insidious (2010) that the creepy remix of child-like songs became a popular sensation for horror marketing. Tiny Tim’s cover of the 1929 song “Tiptoe Through the Tulips” features in James Wan’s Insidious as the titular theme, playing during one of the most alarming scenes from the film, showing a mysterious ghost boy dancing to the ominous song before vanishing in thin air. The distorted wave of vocals in an oddly high pitched yet masculine timbre is genuinely haunting, like something that you would hear playing in your worst nightmare. Since social media has become a playground for dance and audio trends to thrive, “Tiptoe Through the Tulips” has seen a ressuragnce in popularity, particularly featuring on abandoned tour videos and paranormal excursion clips. The intense and petrifying song is rather ironically frigthening as it was originally intended to be a family friendly hit with no shadow of darkness intended. However, it just goes to show you that horror cinema really does have a power in deceiving the atmosphere with music alone.

Disasterpiece may not be a name familiar to the masses, but their scoring for David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows (2014) is a tranxfixing feat pushing the boundaries between screen and viewer. The film takes on a figuratively and literal attachment story where a curse is placed upon victims after acts of intimacy, akin to a ghostly STD. Naturally, the horror of the narrative remains closely fixated to the protagonists, keeping the terror close to home at all times, almost suffocating the audience. To meet the deep personable elements, the scoring too brings a sense of erratic tension to the forefront, where the ticking sounds reminiscent of clock chimes, combined with industrialised synth melodies mimic the overtly present themes of entrapment, doom, and unavoidable mortality.

It Follows avoids the traditionalised use of common soundscapes in favour of upsetting any sense of familiarity the viewer may have had. In a similar line to this is Jóhann Jóhannsson’s melodramatic score for Mandy (2018), which delivers a feast for the ears with every fibre of its being. The presentation seen in Mandy is on its own enough to be fully controlling and visually arresting; when the elements of music are incorporated, any means of affect are amplified to the extreme, with the tinny, industrial tones working alongside psychedelic chargings to create a phantasmagorical palette for the senses.

Powerful contemporparty soundtracks do have one goal in common, which is to stay true to classic genre scoring elements whilst employing a new flavour that is foreign to the listener’s personal soundscape. In a way, this consideration has always been the case. Take for example Fabio Frizzi’s work, the Italian composer and frequent collaborator of Lucio Fulci would consistently marry two polar opposite musical genres (band and orchestra) to birth a theme song so enriched in chaos and commotion that its impossible to break away from the horror unfolding on screen. Frizzi’s scoring for City of the Living Dead (1980) and The Beyond (1981) truly immerses cinema as an audiovisual medium, all in an ode to break away from traditionality and opting for refreshingly original scoring.

Within recent years the use of music within horror has reached a new means where the contextualisation of sound itself is a key plotpoint. This element has always been popular, with films such as The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) thriving in the notion of music. Essentially the subject of sound has always been an integral part of horror.

Additions from modern autuers including Gaspar Noé and Edgar Wright have always relied on the impactfullness of scores to survey the depths of terror, with Noé’s dance studio based extravangaza Climax (2018) using hypnotic numbers playing over extensively long movement shots, and Wright’s nostalgic score for Last Night in Soho (2021) enlisting the help of 1950s-1960s hits to convey a twisted narrative rife with equal amounts of terror and sentimentality.

This idea of reusing hit songs in a new light has been repeated throughout cinema for decades, but when it’s done correctly the effect can be significantly influential over a film’s finished result. One horror that utilises this aspect with flawless execution is Jordan Peele’s Us (2019). Us’s composer Michael Abels remixes the 1995 song “I Got 5 on It” (Luniz), quickly becoming the film’s official theme song. Abels flawlessly highlights the hard-hitting beat and rhythmic structure at the film’s most tense moments, including the heavy home invasion scenes, almost using the beat as a siren or pounding drum that emotively and psychically jolts even the most stern-faced of viewers.

The power of music in horror can be asphyxiating, it can be deliberately troublesome, and it can completely make or break a film. For decades music has been a contraption to manipulate and assemble whatever emotion the film demands.

Looking for more top horror lists and reviews? Check out our blog here..

![An American Werewolf in London' and Its Iconic Transformation [It Came From the '80s] - Bloody Disgusting](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/american-werewolf-london-e1585840708232.jpg)