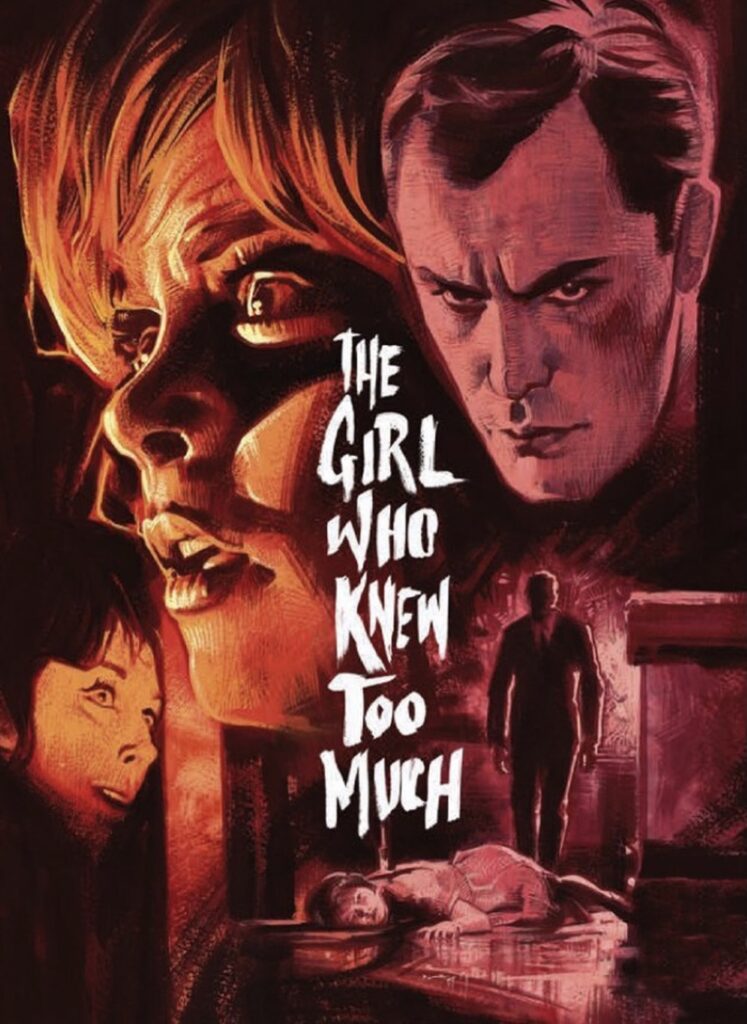

1- The Girl Who Knew Too Much (Directed by Mario Bava, 1963)

Nora Davis (Letícia Román), an American tourist visiting Rome is viciously mugged and knocked unconscious, upon awakening she witnesses a brutal murder. Nora reports this to the local authorities, but no one believes her. After a cryptic phone call she fears she’ll be the killer’s next victim and sets out on a frenzied mission to find the murderer.

Bava’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much is largely considered to be the first giallo film, this full-bodied tale extracts archetypal horror elements such as threat, an illusory killer, and brazen imagery. Bava furthered these already established cinematic elements through exercising an accelerating level of suspense that will be seen across future giallo cinema. The film also creates an ever rising tension through employing a stark cinematography that basks in chiaroscuro shadows and transports the viewer into a dream-like world where the visuals completely take over. It can be said that The Girl Who Knew Too Much was inspired by the master of suspense himself, Alfred Hitchcock. Films such as Psycho thrive on this mentioned mystery and the whole thrill of the ‘whodunnit’ story. Throughout the film we are taken on this journey of discovery with Nora, the viewer plays a part in her involvement with the case. Future giallo films continued to use this

aspect of witnesses aiding investigations in retaliation to their fears of being the next ‘victim’. Thus establishing the authorities to be a secondary character whose importance is noted, but never fully deserving of any credibility as the protagonist typically solves the case on their own.

As it was early days not every key essence of the sub-genre was featured in The Girl Who Knew Too Much, but what was established is the essence of what makes giallo cinema so recognisable, the element of judicial interference and stark visuals.

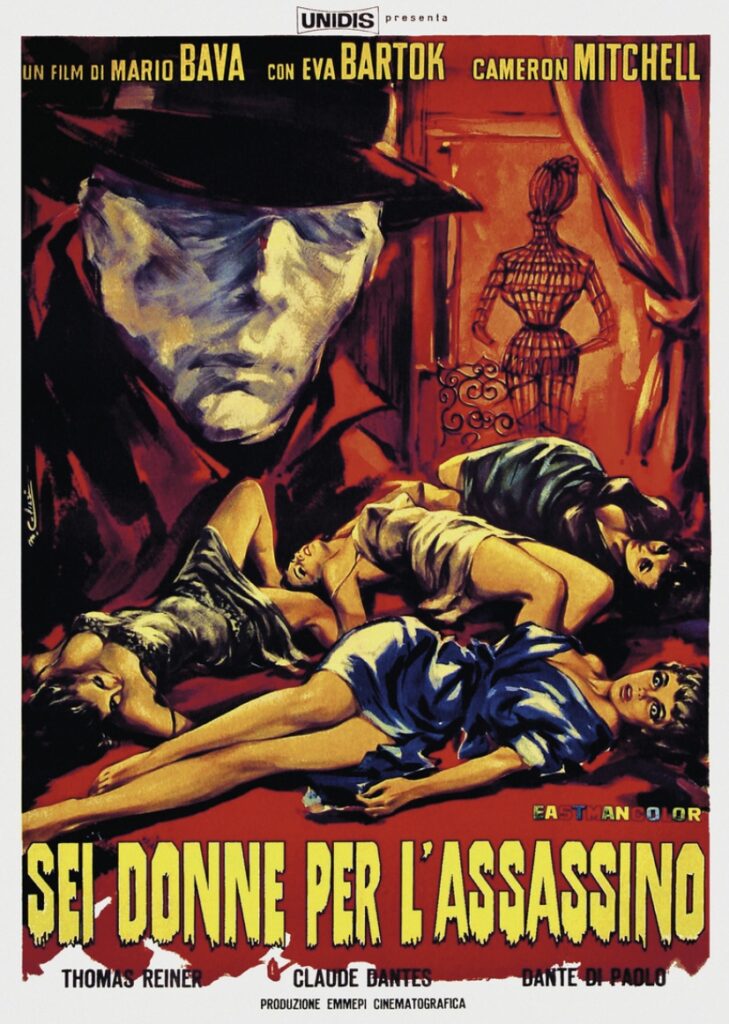

2- Blood and Black Lace (Directed by Mario Bava, 1964)

Model’s at a fashion house in Rome are killed off one by one by a mysterious faceless killer with metal clawed gloves.

It seems that The Girl Who Knew Too Much left a mark on Bava’s cinematic inspirations as Blood and Black Lace was made soon after his 1963 breakthrough. The film hones in on everything that defines giallo. There is not an element that isn’t ticked off from the genres checklist, with a vivacious colour palette, a covertly dressed killer (trench coat and gloves), and sensualised murder scenes. The film pushes the boundaries that were creatively established during 1960s filmmaking, such as clear plots and a linear narrative. Each scene is treated delicately, there isn’t a single moment that hasn’t been carefully curated. For example, each death is warmed with a rich, elegant lighting that dares you to carry on watching and embrace the beauty amongst harrowing images. The film is set in a fashion house, meaning that couture and chic stylisation are at the core of the mise-en-scene. Plenty of lavish silks and velvets feature in several kill scenes, prominently forcing this contrast between harm and sensuality.

At the time the implementation of eroticised gore was definitely a sight for sore eyes, little did Bava know that this would be a key factor in giallo’s progression.

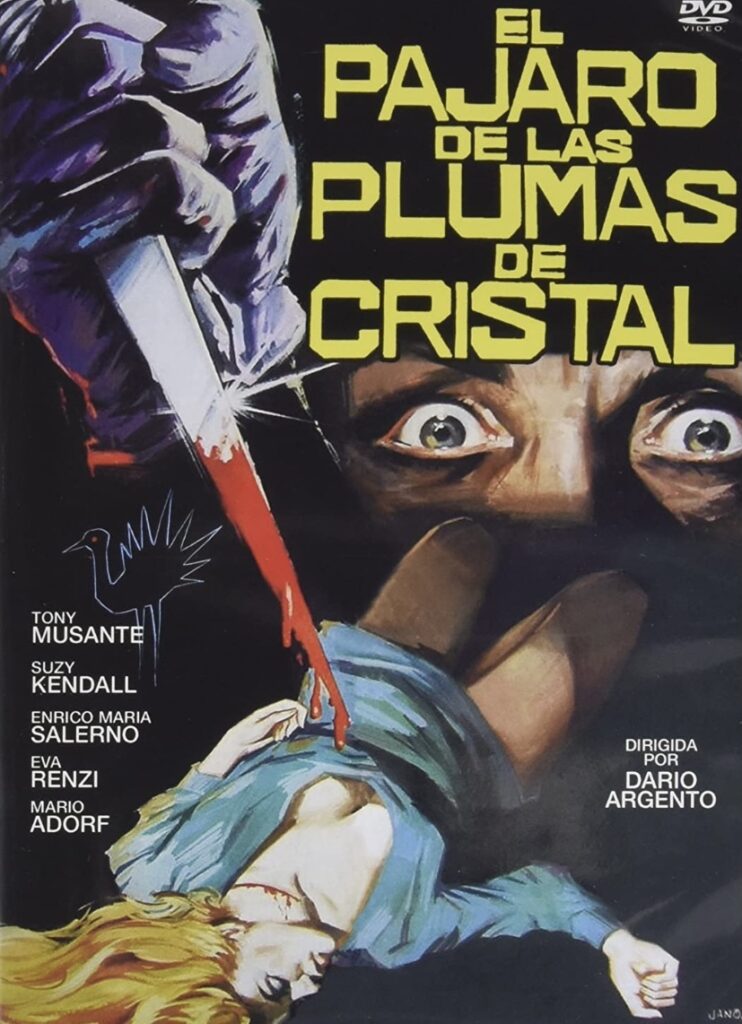

3- The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (Directed by Dario Argento, 1972)

American writer Sam Dalmas (Tony Musante) witnesses a murder attempt by a black gloved assailant in an art gallery. The killer is suspected to be a serial murder who is killing young women across the entire city. As a key witness Sam must help the police in their ongoing investigation before he becomes the next victim.

Argento and giallo is a match made in heaven. There’s a reason as to why Argento is heavily tied to Italian horror, it’s his melodic combination of textured conventions and stylised symbolism that melts the barrier between horror and art. His early work of The Bird with the Crystal Plumage gets majorly overlooked within his filmography, but it is one of the richest films lurking within the entire genre. Bava may have given giallo its first lease of life, but Argento’s early work thickened one of the most important essences that would be seen in future giallo classics. This film revels in its own ludicrousness, the incoherent why’s, when’s and where’s of the murders are almost comically hazy, it wouldn’t be surprising if audiences even became irate at the films ‘big reveal’. Despite the ill-defined conclusion, it somehow works as a consequence of Argento’s fever dream bravado that takes the wheel throughout the film. The story (as does most giallo’s) works on coincidences and deceptions, moulding bizarre worlds that are supposed to take place in reality, but always seem disorienting.

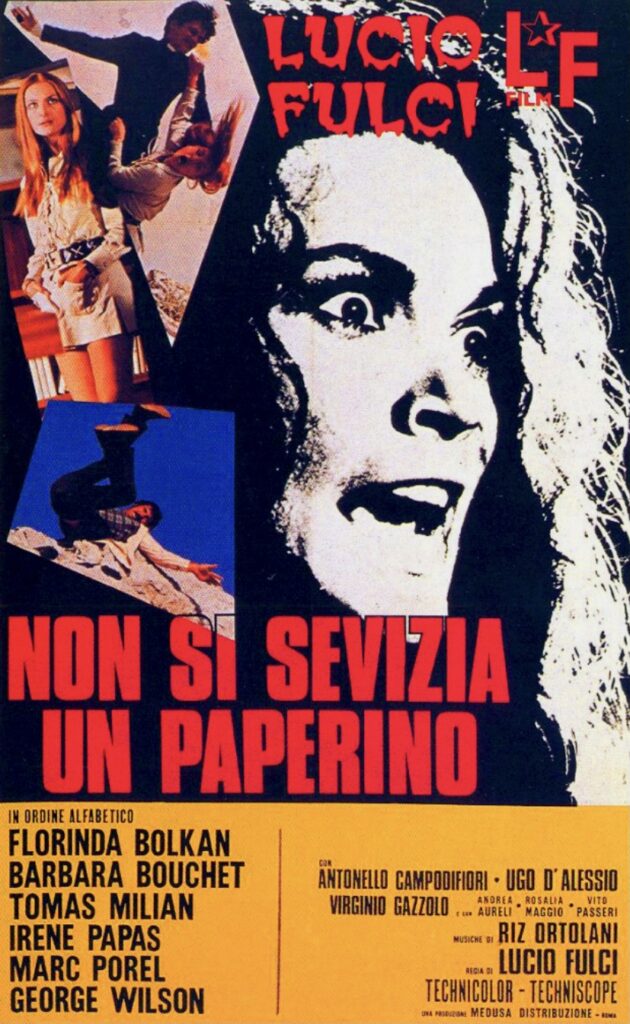

4- Dont Torture a Duckling (Directed by Lucio Fulci, 1972)

Chaos erupts within a small Italian town when it becomes clear that a child killer is on the loose. A reporter and the police must band together to find the culprit before it’s too late.

Fulci within his own right is very much a key player within giallo cinema, Don’t Torture a Duckling is actually known to be an introductory film for many wanting to get into the genre.

This film aided the bleakness and alienation of society that the genre thrives upon. The picturesque village may be pleasing to the eye, but beneath the surface is a corrupt town overflowing with perversion, paranoia, threatening attitudes, and simple-minded ignorance.

Fucli dares the viewer not to applaud the braveness of the film’s themes. Sins, guilt, and repression are at the heart of the killer’s motives, which is primarily implanted through the heart of religion. This expression of sexuality within the village’s church is openly scrutinised by Fulci, in fact the town’s church is almost a central character, an antagonist. The notion of utilising religion as an ironic storytelling piece continues throughout 1970s giallo films, particularly in What Have You Done to Solange?

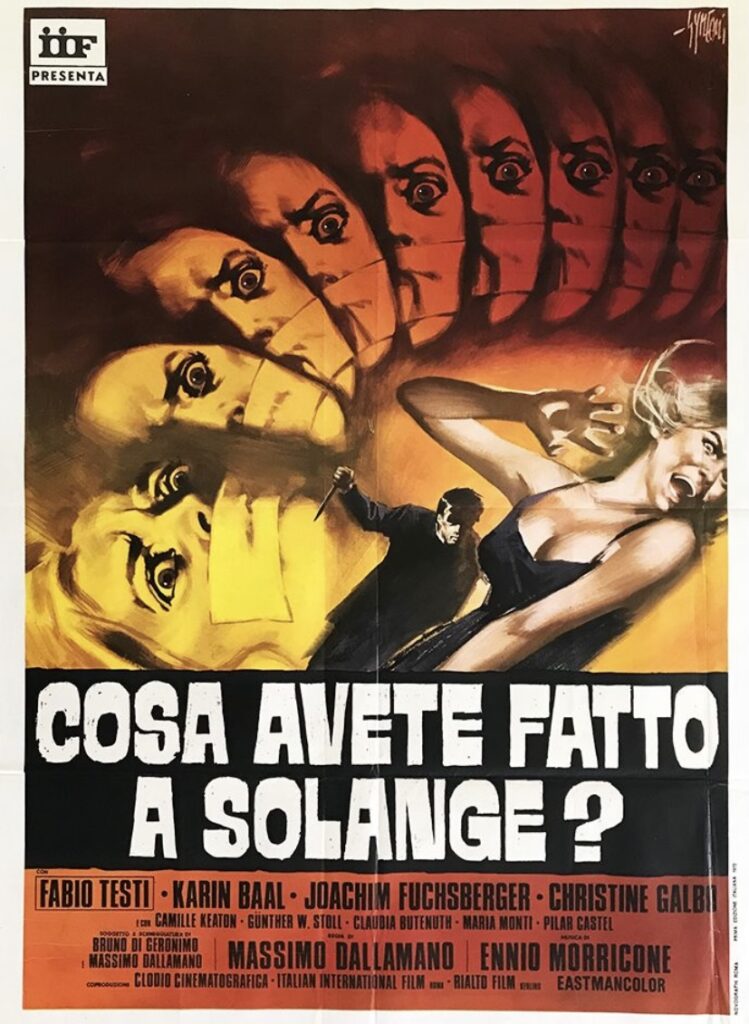

5- What Have You Done to Solange? (Directed by Massimo Dallamano, 1972)

Students at St. Mary’s Catholic School become the target of a sadistic serial killer. A teacher at the school becomes a suspect after his suspicious behaviour with the students arises, but the dots are not connecting, leaving the killer out on the loose.

1960s and early 1970s cinema was rife with cult sub-genres melting with each other to form hybrid films such as What Have You Done to Solange?, gaining extra profit and merging various stylisations. The film masterfully creates surreal landscapes swarming with nightmarish thrills, jolting the viewer. Dallamano’s 1972 horror combines German Krimi cinema (City settings, cop thrillers, and revenge plots) with giallo to create one of the most underrated horrors to come from the 1970s. The catholic girls school setting delights itself in crude stereotypes, particularly that of exploitation amongst women. Whilst it’s not perfect, it is rivetingly entertaining by recruiting a shamelessly sexualised narrative, consisting of vicious kill scenes that Freud would have a field day analysing. Amongst all the hurrah of utilising taboo’s as a provoking tool, Dallamano does not forget the importance of the film’s visual flare. Each scene is painted with a quaint background of mundane terrains, but the dose of gruesome terror leaves a burning mark on the viewer, forcing an unforgettable reputation.

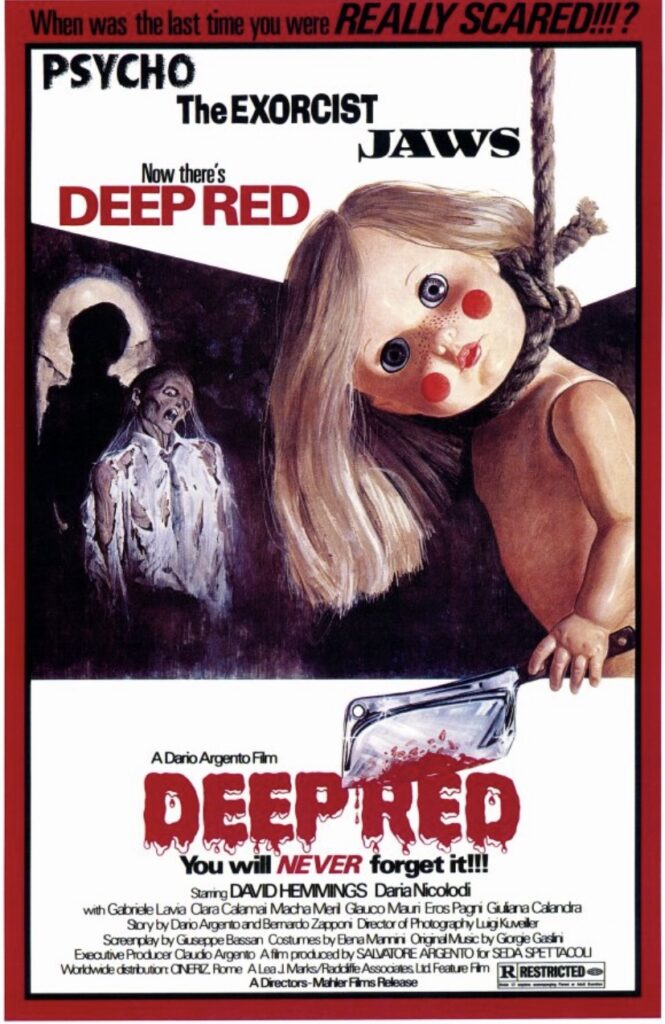

6- Deep Red (Directed by Dario Argento, 1975)

Musician Marcus Daly (David Hemmings) discovers the body of a murdered psychic medium. Leading Marcus and reporter Gianna Brezzi (Daria Nicolodi) to take it upon themselves to solve the case.

Deep Red is known as one of Argento’s finest films, with the dizzying aesthetics, kaleidoscopic colour palettes, hazy perspectives, and impressive score securing a flourishing acclaim. Every scene creates an unfamiliar world where the tension grips onto the viewer and won’t let go, encouraging the audience to dismantle their expectations. Giallo continuously aims to startle, and Deep Red is one of the best examples for showing how and why horror is more than just quick scares and gore. Argento employs intricate camerawork that gives the result of a finely choreographed production. Rather than keep the camera still throughout the film, like a fly on the wall, Argento dances the lens around, emulating hectic and frenzied auras that make the panic of the kill scenes even more erratic and disturbing. Furthering this avoidance of stillness is the abrupt and shocking ending. Giallo may be known for its big reveals and double twists, but most of the time these revelations are so illogical and blasé that the viewer is left with more questions than answers, but Deep Red uses the infamous ‘red herring’ trope as a significant plot point in the investigation. Deep down the audience have known who the killer is all along and are told very much early on within the film. Sometimes the true horror doesn’t come from the unexpected, but what we already know.

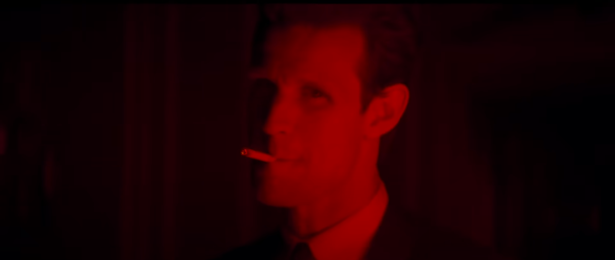

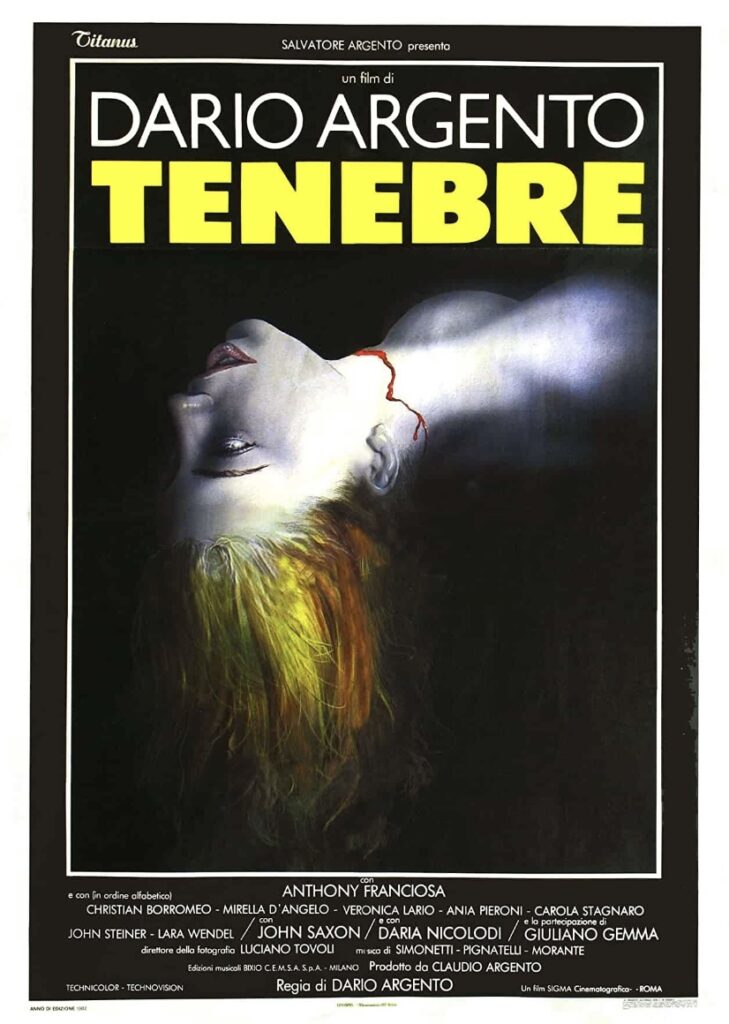

7-Tenebrae (Directed by Dario Argento, 1982)

Successful author Peter Neal (Anthony Franciosa) receives a letter from a suspected serial killer claiming that Neal’s books have inspired them to go on a killing spree. Soon after Neal becomes involved in the investigation to catch the killer before it’s too late.

As the 1980s began giallo cinema progressed and became fairly popular amongst mainstream audiences. The unholy trinity -Argento, Bava, and Fulci- had solidified a decent name for themselves as giallo masters, and with this popularity came a shift within the genre. There was a growing demand for slashers resulting in films such as Tenebrae becoming more operatic and less confined within small Italian landscapes as an attempt at branching out. Tenebrae is a key film in both eighties horror and giallo cinema thanks to the packed narrative that manifests into a convoluted extravaganza, encouraging the viewer to become lost within the mad world created. In fact the narrative is mostly of secondary importance, the story beats serves only a progression-based purpose for the kill scenes to shine, forgoing typical cause and effect.

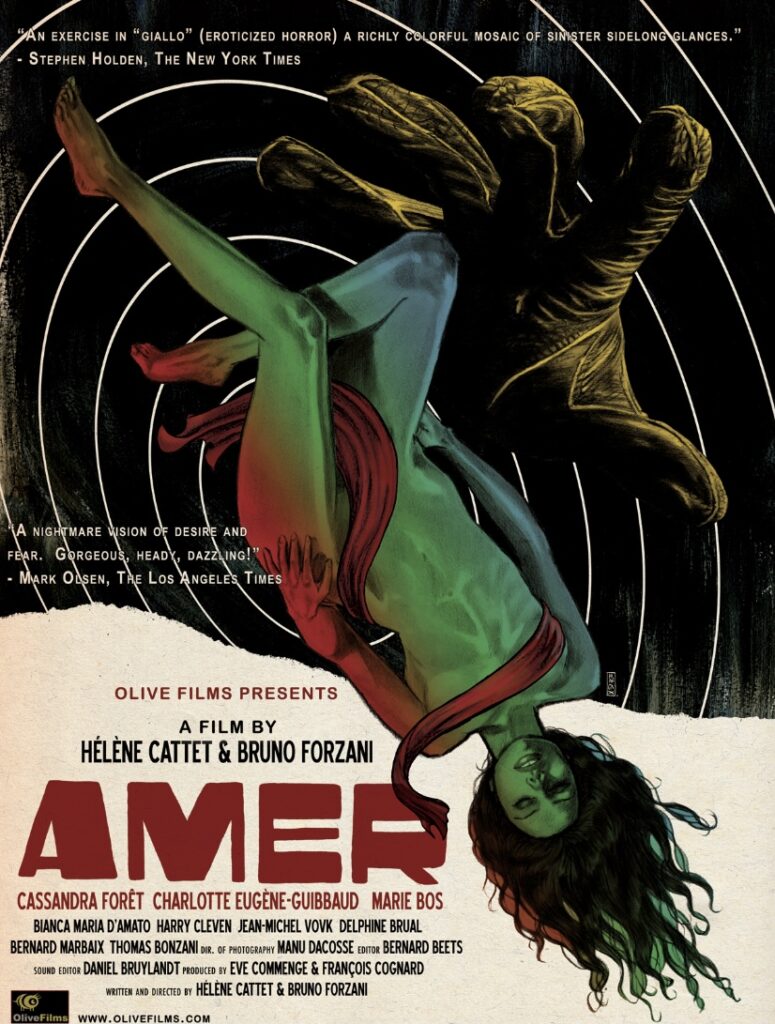

8- Amer (Directed by Hélène Cattet & Bruno Forzani, 2009)

Amer follows Ana throughout her childhood, adolescence and womanhood.

Amer is a haunting and mystifying neo-giallo told in three parts as we witness three key moments throughout various stages of Ana’s life. Amer acts as both a retelling and a homage to great giallo cinema. The visual format in which the film is told reads exactly like Suspiria and Tenebrae, with the film’s nods towards neon lighting and duality (both metaphorically and technically via the continuous use of split screen). But rather than copy directly, Cattet and Forzani use giallo films as a creative vessel for their own highly original work to pour through. The displaced narrative never meets a clear conclusion, in fact the film plays out in almost an entirely surrealistic tone, drowning any chance at linearity.

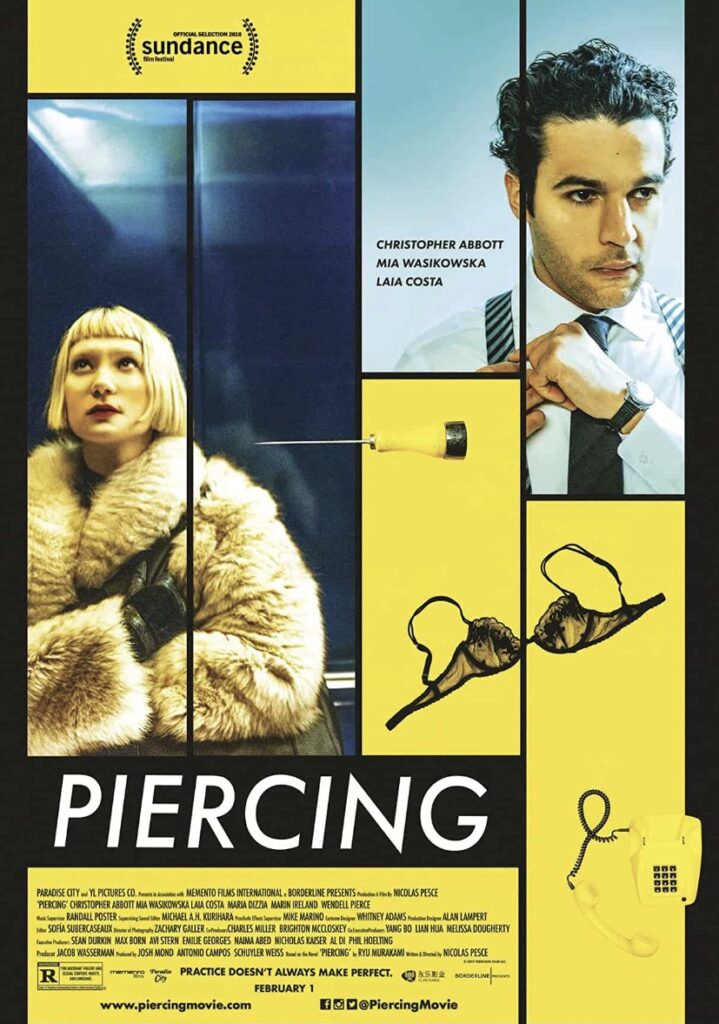

9- Piercing (Directed by Nicolas Pesce, 2018)

Reed (Christopher Abbot), comes across as a normal family man with a loving wife and newborn baby waiting at home, but this is all a facade. Underneath the disguise he hides a dark desire to kill.

Piercing is one of those films where the simple plot premise spirals out of control action by action. The enigmatic whirlwind of events do not allow the viewer to breathe at all, instead you are stuck on this disastrous rollercoaster alongside Reed as his night shifts from one mishap to the next. It is difficult to line this film up alongside notable giallo films as Piercing is entirely individualistic, but the spine of the film comes from the complex relationship between psychology, sex, and violence. Pesce aligns these three devices to interweave a tale ridden with interesting politics reminiscent of Argento and Bava’s work.

10- Knife + Heart (Directed by Yann Gonzalez, 2018)

Anne (Vanessa Paradis), is a filmmaker who specialises in gay pornography. Her life begins to crumble when her editor and partner Loïs breaks up with her. To win her back Anne hatches a plan to make one of the most riskiest film’s yet, but when a string of horrid murders occurs both the production and Anne’s life is threatened.

Knife+Heart erupted onto the horror scene with a unique magnetism that dedicates itself to honouring giallo cinema. The overall tone is electrifying without being distractingly flamboyant, most of the film’s allure is actually drawn from the characters lack of satire. The viewer sympathises with Anne and her film crew, and although the giallo elements ensure that boredom does not become an issue, the film grounds itself through the cultural connotations.

Throughout giallo films the police are seen as rather incompetent, with the outsider being the one to solve the crime (à la The Girl Who Knew Too Much), Knife+Heart continues with this tradition but in a new light. The police appear to dismiss the murders and refuse to raise alarm in response to the victims being gay men, forcing Anne and her friend Archibald (Nicholas Maury) to hunt down the killer themselves. Pesce regenerates the giallo movement in a modern perspective through exploring an exploitative based storyline but through a rare melancholic disposition.

Love Giallo? Check out our new merch here.