2025 Horror Anniversaries

The Witch (Directed by Robert Eggers, 2015)

Robert Eggers has become a prodigy in contemporary gothic horror, creating films that ooze a rich, dramatic aura that presents historical, period-based tales of folklore and mythology. One film in particular that kickstarted his now cemented reputation as a historical-fiction director is The Witch (stylised as The VVitch). This 1630’s set horror follows a Puritan, New England family whose quiet life is turned upside down after being banished from a commune after a religious upset.

Even to the history experts, The Witch is said to be rather accurate, with Eggers ensuring that every detail was written with consultation from specialists on 17th-century agribusiness, ensuring that the film is as authentic to the subject material as possible, therefore aiding the integral presence that the film so flawlessly achieved. Every inch of screen time has this otherworldliness about it; a ghostliness that speaks to disturbed pastimes and the horrors that still haunt to the present day. Although The Witch is only celebrating its tenth birthday this year, its striking effect is set to tread the genre for a long time to come.

Hostel (Directed by Eli Roth, 2005)

Although it has been a whopping twenty years since its release, Hostel still stirs quite a contentious reaction to this day. This Slavic-set film follows the brutal fates of three backpackers who are unknowingly lured into an underground organisation where members pay to torture unsuspecting victims. Upon its release, many audiences were shocked at the film’s graphic displays of violence and appalled that this is what mainstream horror had evolved into.

Indeed, there were a good handful of viewers who got stuck in with the mountains of bloodied gore, creating a boom of the ‘torture-porn’ subgenre that rocked the horror scene in the mid-2000, yet much of the public opinion was that Hostel was essentially heavy-violenced smut. Hostel thrives in its own griminess, whether that be the gritty storyline or the extensively grungy, brutalist vibe of the film’s various torture lairs. By today’s standards, Hostel is tame, but its rude arrival on the scene propels the film to be a contemporary classic.

Seven (Directed by David Fincher, 1995)

Seven might not be marketed as a horror film, yet the David Fincher directed ‘thriller’ is certainly horrific and based on a terrifying concept. Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman star as the detective duo ‘Mills and Somerset’, desperately trying to solve a series of murders committed in a pattern following the seven deadly sins. As the film goes through the deaths conducted under the guise of the sins, ‘gluttony’, ‘greed’, ‘sloth’, ‘lust’ and ‘pride’, the viewers undergo a viciously cruel string of emotions, as we experience disgust and fright at the hands of the film’s evil killer ‘John Doe’ (Kevin Spacey).

However, nothing could prepare you for the final act, where the last two sins ‘envy’ and ‘wrath’ are acted out. Elevating the daunting narrative is the film’s sharp aesthetic which is just as visually dark and morbid as the film’s content. Fincher is said to have wanted to make Seven appear as a black and white film, but in colour; recreating the sleek shadowing of noir thrillers, with the added electric jolt that colour films can create. To say that Seven is entirely cruel and boldly immoral is an understatement, with this film still being as wickedly brilliant even thirty years later.

Fright Night (Directed by Tom Holland, 1985)

Tom Holland’s extensive career in the horror scene, directing the likes of Child’s Play (1988) and Thinner (1996) started forty years ago when he made his directorial debut with Fright Night, a film that follows a horror fanatic teen, Charley (William Ragsdale) who discovers that his neighbour, Jerry (Chris Sarandon) is a vampire in disguise. Determined to put a stop to the creature, Charley convinces TV vampire hunter Peter (Roddy McDowall) to join forces and destroy the blood-sucker once and for all. Fright Night has the nostalgic, charged energy of 1980s horror, where off-kilter humour mixes with a vibrant sense of terror, in turn forging an unforgettable viewing experience that makes for an excellent watch time after time. Essentially, it is a film that epitomises the offbeat, monstrous mayhem of classic horror, swinging a plethora of hooks and jabs of vampiric madness into the essence of the story, prompting a finished result that is still as electric today as it was forty years ago.

Demons (Directed by Lamberto Bava, 1985)

Equipped with a form of strangeness, a slightly odd narrative flow that combines moments of outlandish gore with an almost sci-fi-like alien/zombie/demon creature arc is Lamberto Bava’s Demons. Bava, being the son of famed horror director Mario Bava (‘Black Sabbath’, ‘A Bay of Blood’), most definitely has the horror gene pumping through his veins, with Demons being a prime example of a horror film created out of a passion for the genre. The eclectic film takes place in a theatre, where a group of people are mysteriously invited to a screening, only to end up trapped in a true nightmare as green-drooling demons take over. The metafictional qualities are glaringly obvious; the cinema room becoming a literal labyrinth, the ‘film-within-a-film’ premise, the over-the-top, parody-like gore effects and so forth. This unique texture breaks the figurative fourth wall and infests the film with a punchy, refreshing tone that stands out and leaves a lasting impression.

Jaws (Directed by Steven Spielberg, 1975)

Jaws is synonymous with the descriptions of a ‘classic’ film. Quotes are plentiful, the theme tune is an integral jingle to this day which is more than likely already being hummed in reader’s minds, and most importantly Jaws is still as much scary fun now as it was half a century ago. Bar his work on TV movies and The Sugarland Express (1974), Jaws is what kickstarted Steven Spielberg’s household name status, with the film at one point even being the highest-grossing movie of all time.

Whilst it is worth discussing how the film has been infinitely cited as one of the greats and how the United States Library of Congress elected Jaws as being selected for preservation due to its landmark status and appeal, what is a more pressing matter is exactly how and why Jaws achieved its infamy. The film delivers some outwardly funny quips and pockets of dialogue, adding a flush dimensionality to the scares, and putting a bit of flesh on the film’s bones. More so than that, Jaws has genuine suspense attached to the horror. No matter the quantity of watches, the looming threat of chaos and destruction still has an almighty bite to it, entirely absorbing attention and captivating audiences at a seriously impressive rate.

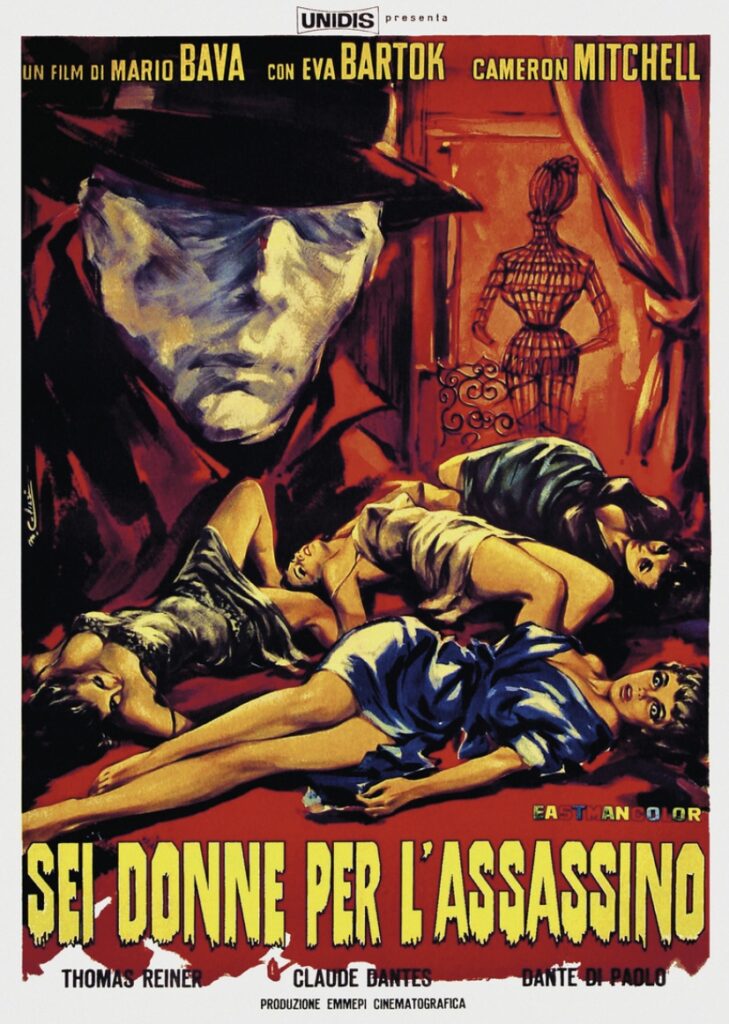

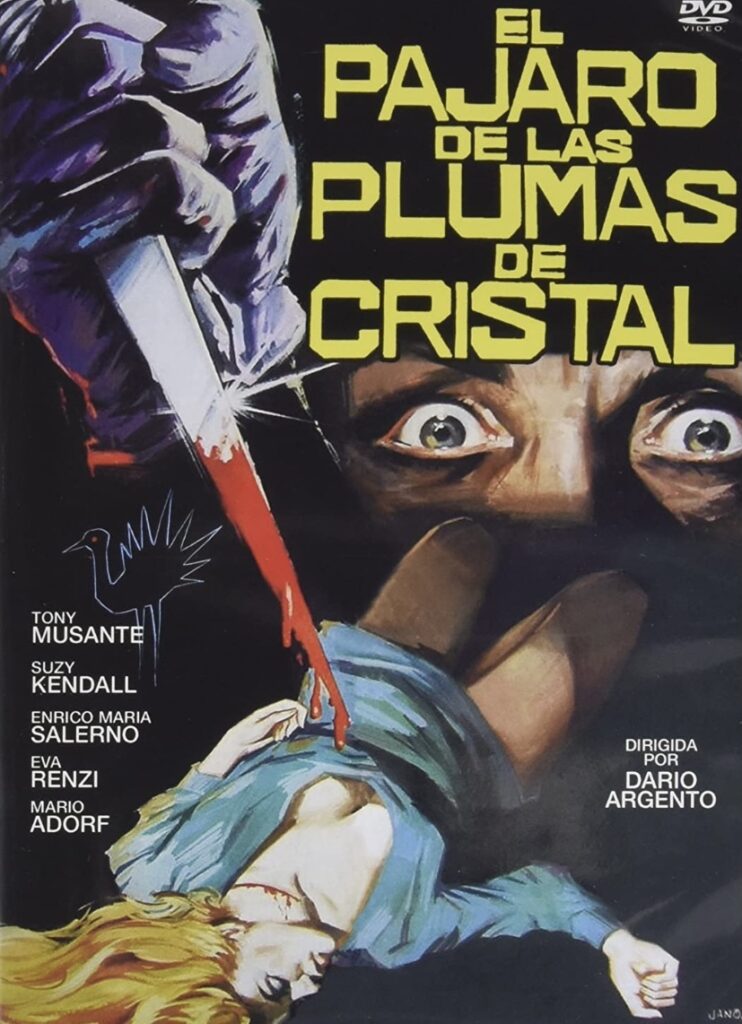

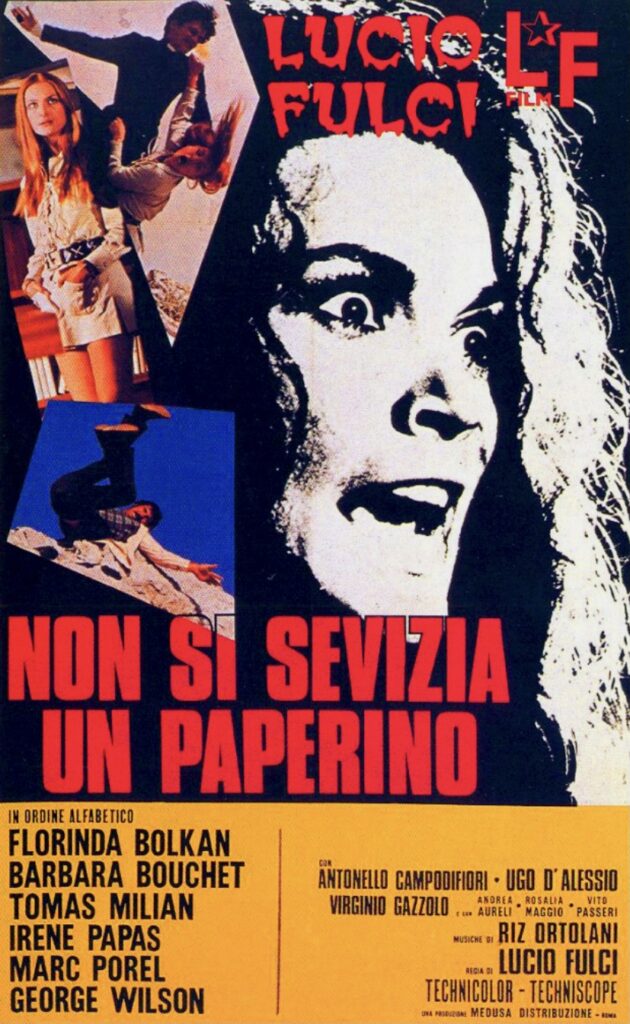

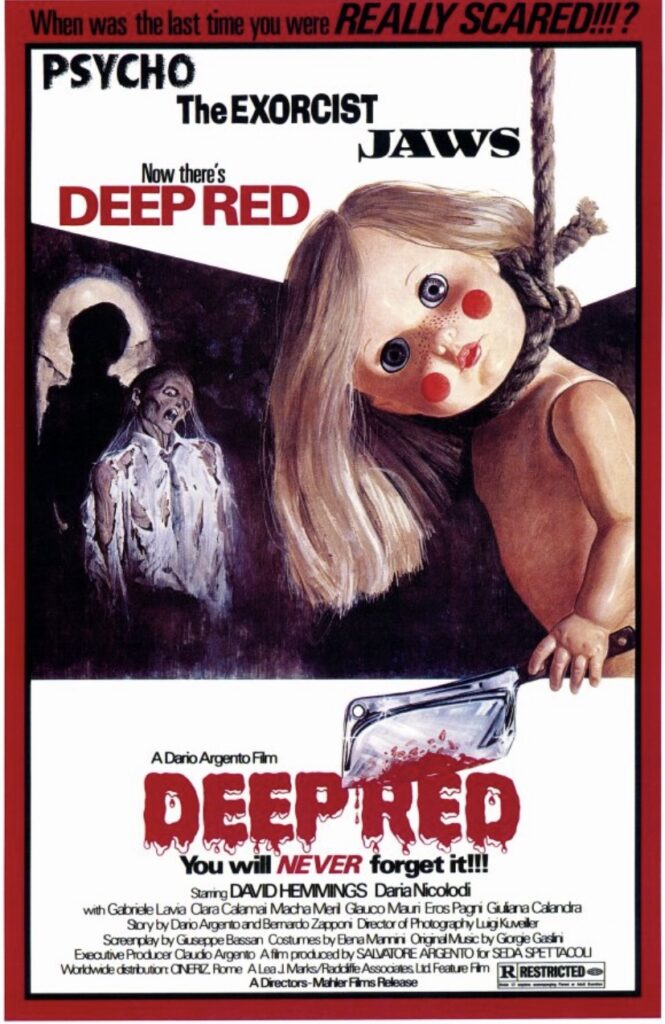

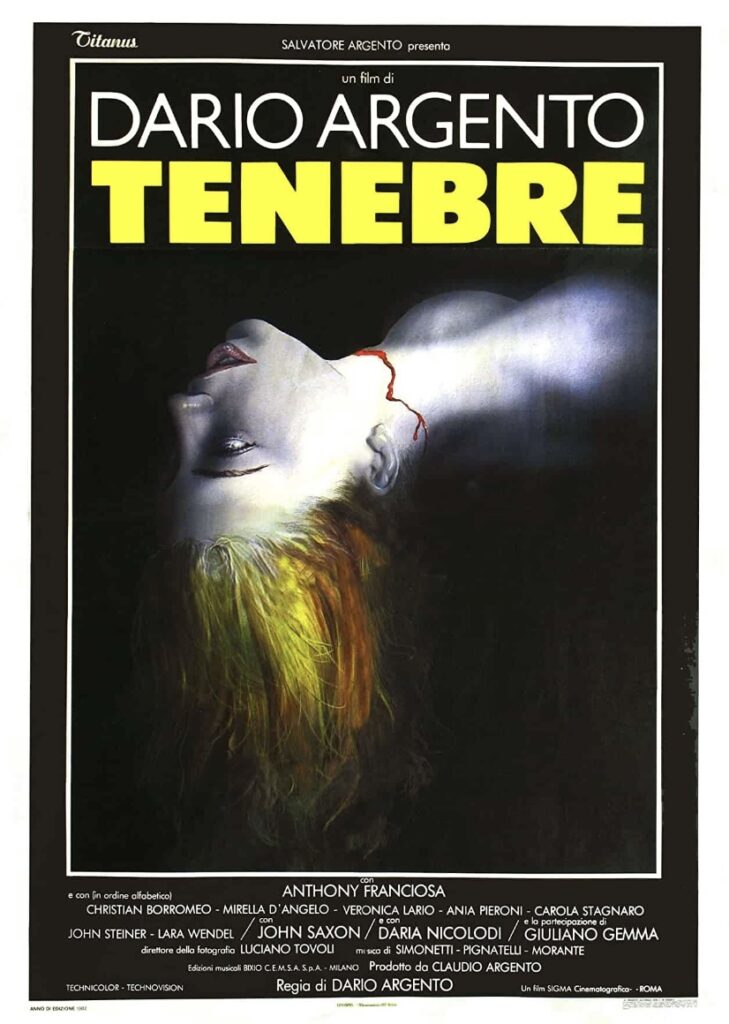

Deep Red (Directed by Dario Argento, 1975)

Dario Argento’s work for horror cinema is nearly unmatched, with the director being the brains behind the likes of The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970), The Cat o’ Nine Tails (1971), Suspiria (1977), Tenebrae (1982), Phenomena (1985), and Deep Red. The film exercises a genuinely terrific compositional structure where the labyrinth of a plot is powered by the camera’s incessant need to be constantly moving, floating and dancing around as it captures the brutal antics that unravel before us.

The flexible nature of the action is further enhanced by its content, which has some truly alarming moments of panic and dread, particularly in regards to the smorgasbord of violent scenes, alongside the inclusion of an awfully creepy puppet. Deep Red acts as one of the giallo subgenre’s most definitive films, with the visual outcome of Argento’s work here being comparable to a visual opera, as the film stirs in elements of murder mystery with sleek stylisations and countless dramatic effects.

The Skull (Directed by Freddie Francis, 1965)

Joining Hammer Film Productions in the run of 1960s British horror was fellow Brit-based company, Amicus Productions, whose credits include The House That Dripped Blood (1971) and Tales from the Crypt (1972). One other film that kickstarted Amicus’ fairly successful run in cinema during the sixties and seventies was The Skull, a horror made in colour to challenge the competitive horror market. The film follows the hauntings, hallucinations and possessions that surround the stolen skull of the French libertine and controversial figure, Marquis de Sade. Starring both the iconic Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee is this rather zestful feature that boasts an applaudable assemblage of visionary cinematography that has not aged a day since its release sixty years ago.

Les Diaboliques (Directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot, 1955)

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s French horror Les Diaboliques is coined as one of the true greats, obtaining a stellar reputation over the seventy years since its release, gaining Criterion Collection status and helping cement the tropes that have formed the horror genre. The film is also said to have helped inspire the basis for the legendary Hitchcockian thriller, Psycho (1960). The film follows a conspiracy to murder Michael Delasalle (Paul Meurisse), a cruel headmaster at a boarding school.

The mastermind pair behind the elaborate plan are Michael’s wife, Christina (Vera Clouzot), and his mistress Nicole (Simone Signoret), who merge to create the ‘perfect plan’, however, matters soon turn sour as their scheme unravels. Time has graced this film, with the various twists and turns becoming even finer over the years, as the clever narrative still holds such impact due to its melodramatic, nightmarish and solemn tone that is both haunting and alluring.

Dead of Night (Directed by Alberto Cavalcanti, Charles Crichton, Basil Dearden and Robert Hamer, 1945)

The British horror Dead of Night has become a quintessential piece of cinema that holds gravity in the anthology portmanteau reign of films, the horror genre and the extensive selection from Blighties’ own film market. Dead of Night’s anthology structure captures five sequences, all rounded up by the framing story of a team of guests who join together at a rural country house, retelling their own horrific stories. The impressive line-up includes Sally Ann Howes, Googie Withers, Mervyn Johns and Michael Redgrave, who all bring their own special zing to each segment, taking heed of the elaborate lore, fables and legends from the individual stories.

Although Dead of Night will see its eightieth birthday in September of this year, the film is very much alive. There are countless memorable snippets that still stand out from the film, but one particularly notable example surrounds the seriously unnerving ventriloquist dummy that stars in one of the segments. The unhinged puppet is nothing less than sinister and more unsettling than many contemporary attempts at capturing possessed puppets.

Want more top horror lists and reviews? Check out our blog here..