The figure of the werewolf habitually ignites a viscerally violent vision of one’s own inner self; bestial, carnalous and rage filled. The werewolf is a staple in the long list of monsters that has been constructed throughout time, with its counterparts being vampires, ghouls, witches, and zombies (all continuously appearing in the Halloween costume aisles for years).

The significant prevalence of the creature of the wolf has lied within mythology dating back to ancient paganist times. This rurality and earthliness that the werewolf obtains in defying against systematic patriarchalism only contributes to the enhancement of the monster.

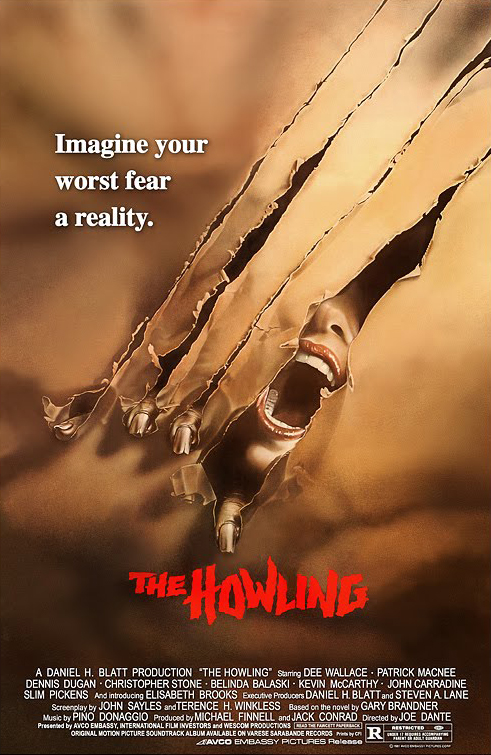

The generalized mythology of werewolves is one that has injected itself into horror for decades now, with Universal Pictures releasing Werewolf of London (Stuart Walker, 1935), followed by The Wolf Man (George Waggner, 1941). Through early cinema acknowledging the transgressive nature of werewolves, the monster has adapted and has become rather indispensable within horror. One film that entirely embraces the creature’s violation of societal norms is Joe Dante’s The Howling (1981).

The Howling follows Karen (Dee Wallace), a television news anchor who travels to a secluded resort (known as the ‘Colony’) with her husband Bill (Christopher Stone) to treat her amnesia after a brutal attack. At first glance the Colony is a scenic place of calmful bliss, where Karen can heal from her trauma. However, little do they know the resort is inhabited by bloodthirsty werewolves. Dante’s reputation for ‘over the top’, comedy filled horror’s began in 1978 with Piranha.

Although many audiences at the time were slightly dissatisfied with the aim of creating a purpose built b-movie, retrospectively Piranha is beloved as a cult classic. The Howling which was adapted from a 1977 poem written by Gary Brandner deters almost entirely from its source material, but the drifting certainly works in its favour. Rather than sticking to the basis of the poem, Dante along with writer John Sayles concocted a self-aware script brimming with a heavy satirical attitude.

Forty years after its release the film still has a good bite. The lashing’s of referential nods to cinema is a delight to watch, as many characters are named after directors who dipped into lycanthropic films including The Curse of the Werewolf (1961) creator Terence Fisher. Besides those more obvious inner jokes is a series of ‘blink and you’ll miss it’ moments such as Dante’s inclusion of the book Howl (Allen Ginsberg) on the counter, as well as wolf based artwork featuring throughout the Colony. Matching the witty gags is the overt exposition of dramatic themes such as assault, trauma, adultery, violence, and perversion. But instead of presenting the film as a crucifying tale of sorrow and cruelty, Dante paints the scene in an entertaining yet aware tone.

The Howling stays true to 1980s horror, as the above mentioned pinnacle points are enveloped in spontaneously fun scenes. The iconic scene featuring Bill and the nymphomaniac werewolf Marsha (Elisabeth Brooks) ‘making the beasts with two backs’ exudes a prominent animalistic energy that werewolves are known for. Their joint transfiguration into their true wolf form symbolically stands for the breaking of bodily barriers that mere humans are physically incapable of performing. The Howling focuses on glamorizing the viciousness of werewolves; they can transgress further than any other being ever could. To a certain extent they allow their darkest urges to take over, through baring their fur and erecting their claws.

Although The Howling embraces this Freudian concept of inner identity, Dante refuses to succumb to pure psychology. We do not feel as if we are watching a harrowing tale of bestial passion, but instead a zealous exploration into horror’s most entertaining creature.

The Howling creates this amusing aesthetic through its quick pacing and energy that certainly packs a punch. Each scene bounces to the next in a successful attempt to avoid a moment of dullness. Accompanying the lively stride that Dante infuses throughout is the noteworthy practical effects that still hold up to this day. Despite the marvellous technology that allows for filmmakers to have great freedom in their films, there is something very special about old school practical makeup effects that take centre stage.

The character design of the werewolves focuses on exaggerating their hunched backs, long tails, matted fur and signature facial features. The creatures of the Colony were made at the hands of Rob Bottin. Across his career Bottin has worked with John Carpenter on The Fog (1980) and The Thing (1982), and has received a Special Achievement Award at the 1991 Academy Awards. Bottin had to take over from Rick Baker after he left production to work on An American Werewolf in London (John Landis, 1981), despite this brief setback Bottin excelled in creating graphically gruesome beasts. One particular look that remains acclaimed to this day is the transformation of Eddie Quist (Robert Picardo). His metamorphosis into a werewolf avoided the use of camera tricks and relied upon creative ploys such as employing the use of ‘air bladder’ effects to give the illusion of flesh swelling and bursting.

The Howling went on to produce a further seven films, all following a similar basis. The future of the franchise is still being developed as Netflix has joined forces with Andy Muschietti (It) to create a direct remake of the 1981 film. Not much can be said for the various sequels as they are all missing that certain spark that Dante so perfectly captured in the original. It is difficult to pinpoint what allows The Howling to still hold onto its success a whole forty years later, perhaps it was Dante’s unique take on creating a bizarre land of misfit scenarios, or even the film’s moving storyline that is still relevant. But one thing is for sure, it’s hard to come across a werewolf film so embellished in meaning, whilst also relishing in pure bloodshed and chaos!