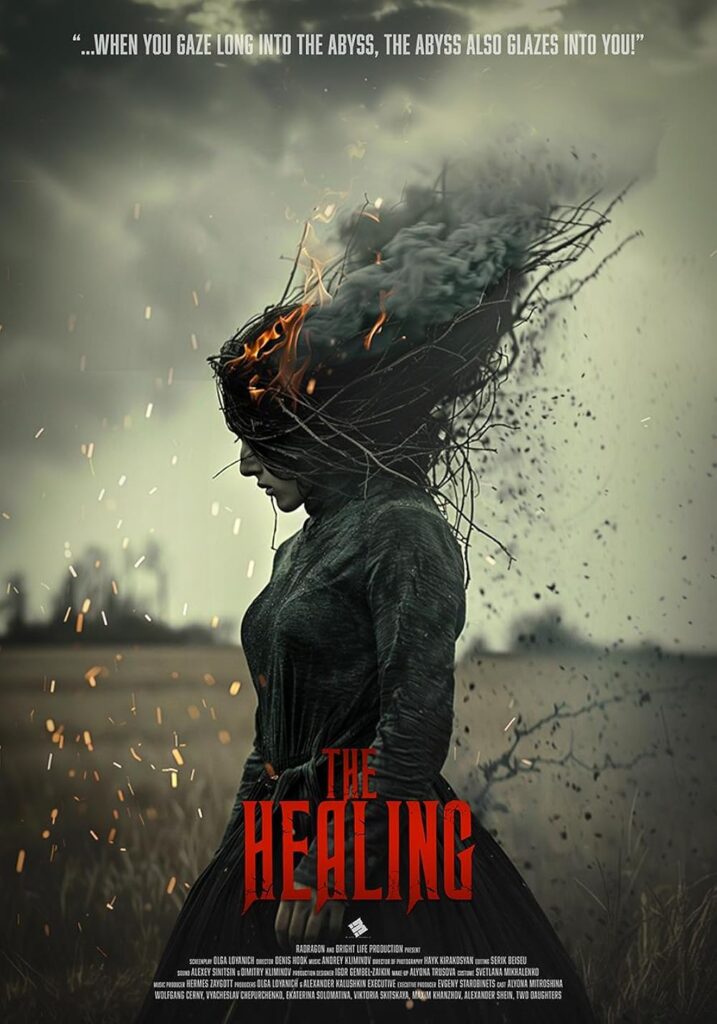

The Healing makes two things clear: be careful who you trust, and be careful of what you trust. This tense and unnerving descent into chaos is an exercise into the dark underbelly that seedily lies amidst seemingly tranquil and ‘healing’ situations…

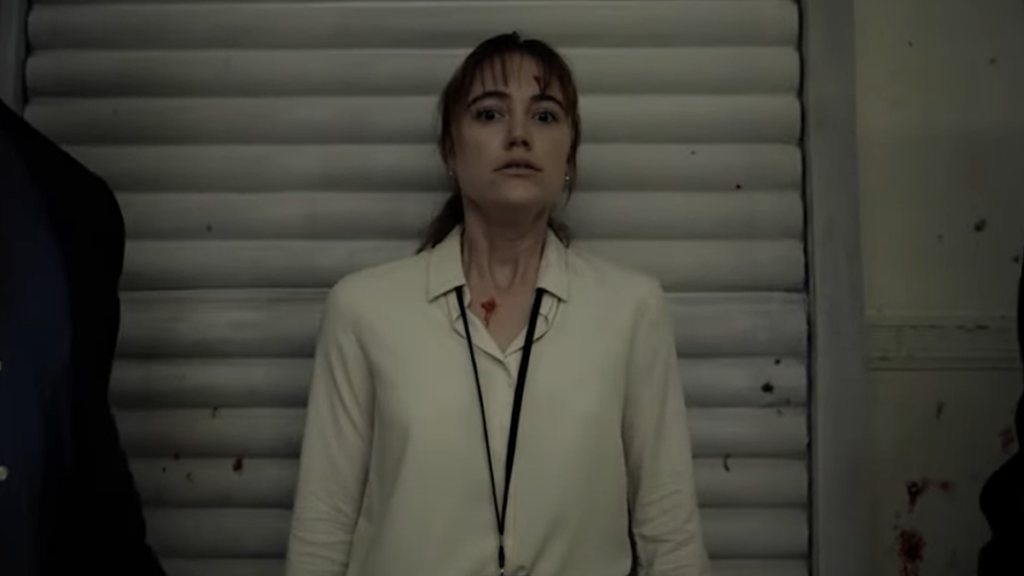

The film follows Lyuba (Alyona Mitroshina), who, in a bid to escape from her abusive relationship to Sergey (Vyacheslav Chepurchenko), heads off to a weekend retreat with her friends Sveta (Victoria Skitskaya) and Zoya (Ekaterina Solomatina). The retreat seems warm and welcoming at first, a chance for Lyuba to distance herself from her troubles; however, when she becomes anxious and starts hallucinating and wants to leave the increasingly strange retreat, Lyuba fears that what’s waiting on the outside is far worse.

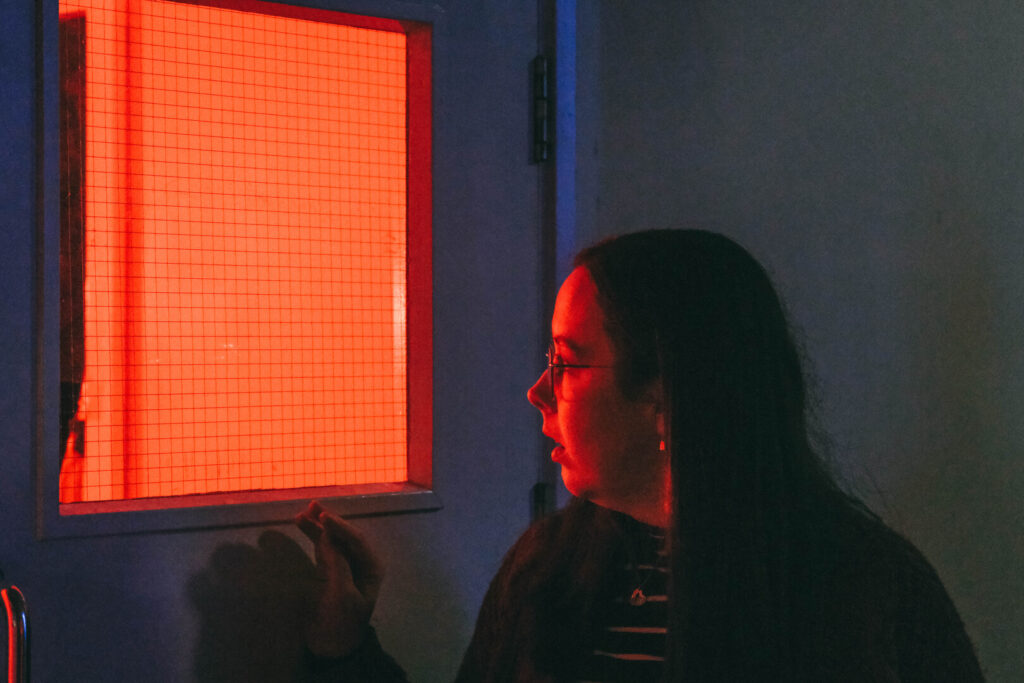

Troublesome woes of domesticity are trickled through The Healing with an appropriateness that gives credence to the gravity of the situation. As Lyuba’s experiences with Sergey are revealed, it becomes clear that matters such as unsettling manipulation and loss of autonomy are central to the film’s effectiveness. The Healing joins the likes of Silent House (2011), Midsommar (2019) and The Invisible Man (2020), where scenes showcasing the erosion of reality speak to underlying concepts that arise from traumatic relationships. Whilst the magnetisation of horror and terror play prominent roles in keeping The Healing entertaining, what director Den Hook ensures is a level of sincerity and solemnity in showcasing such an emotionally deep and courageous film.

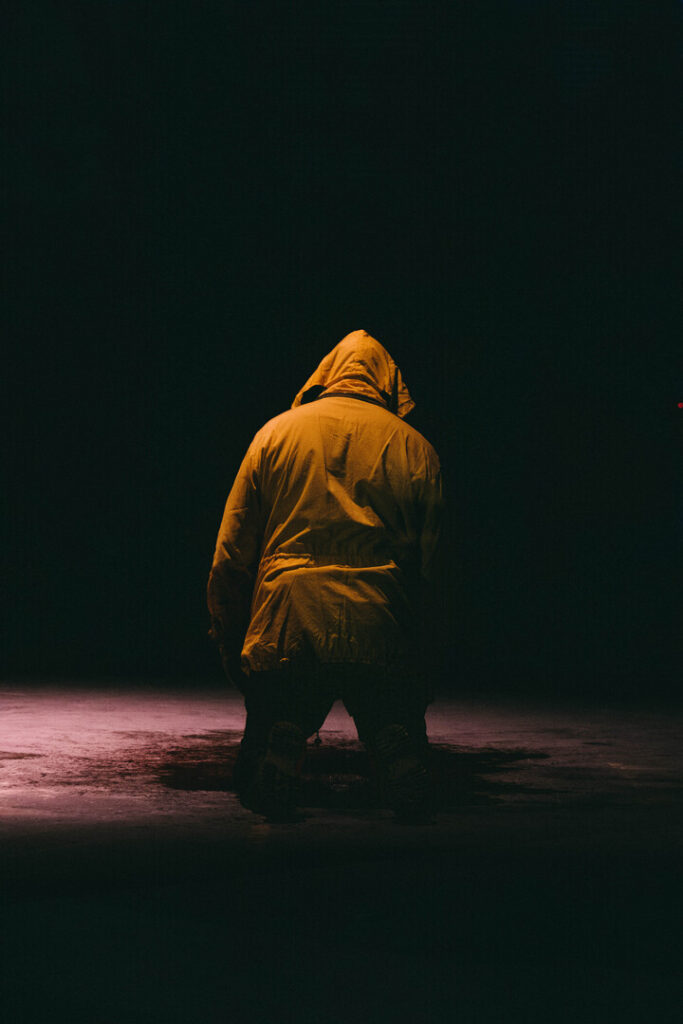

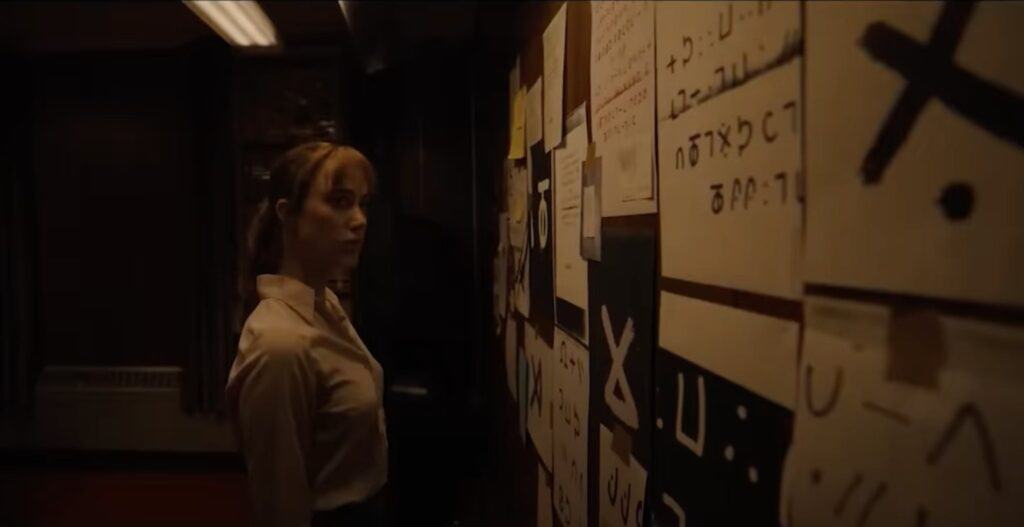

Adjacent to the intense core of The Healing is the film’s isolated setting, which is almost a character within itself. The remote destination of the retreat replicates an intense feeling of remoteness, which outwardly represents the serenity that such a supposed haven should have. Yet, the vast openness of untamed woodlands teeming with towering trees and sweeping landscapes exploits the psychological paradox of the film. The seemingly endless spaces of land harness a form of affective, emotional claustrophobia, where despite the purported freedom of the sanctum, there is an evocative sense of inescapable surveillance from both Lyuba’s introspective visions and the followers from the retreat.

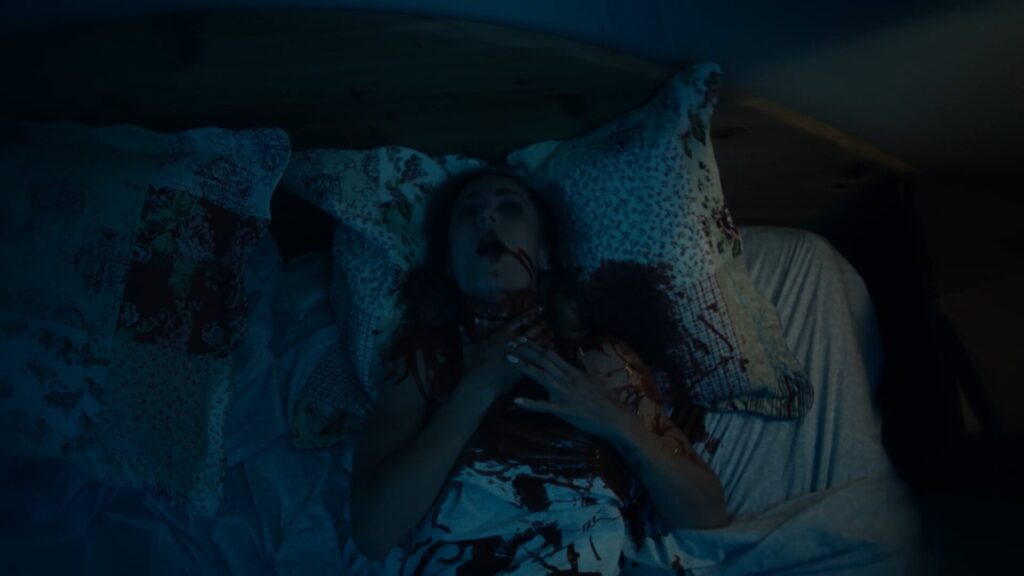

The Healing elevates the already powerful ambience through its parading of subjective reality with the assistance of Lyuba’s intense visions, which she experiences throughout the film. The film often wears a cognisant coat by virtue of Lyuba’s apparitions that embody both a sense of fantasia, alongside startling spells of disorienting horror. The amalgamation of surrealism and unsettling horror lines the film’s double edged sword, with the almost ethereal-like illusions drawing the viewer in, only to stun and disconcert when the reveries quickly become dark, crazed and twisted.

The combined powerful cerebral knowingness of the narrative and the aesthetically striking nature of The Healing works to create a richly detailed and rigorous end product in its means to engage, alert and disturb.

You can catch the film Saturday 28th September at this years festival, tickets here!