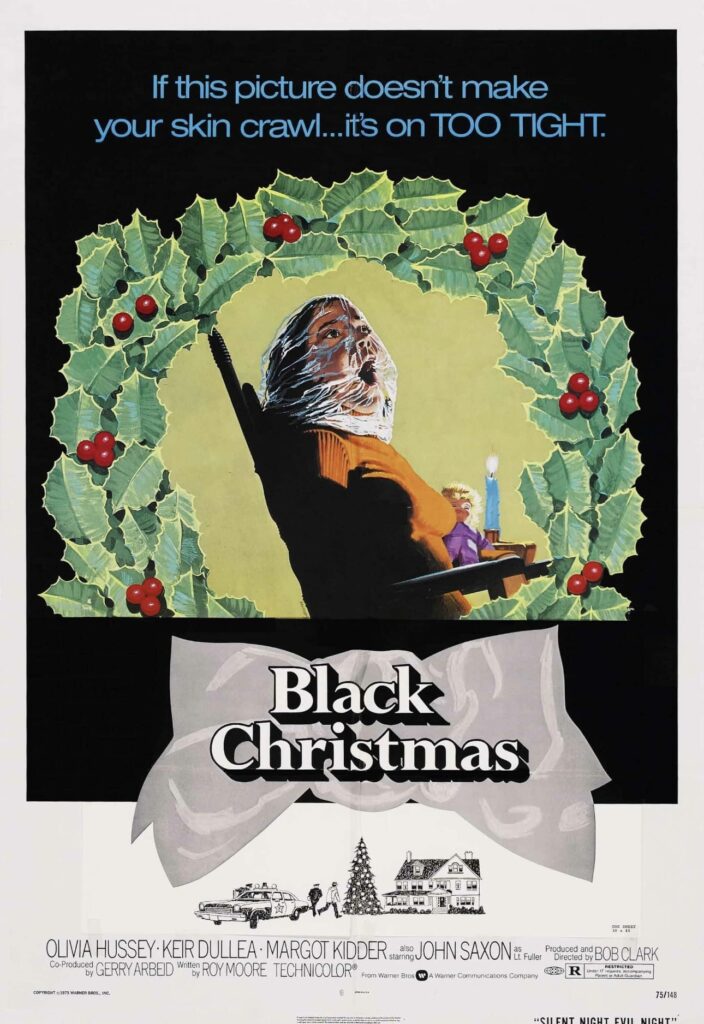

Bob Clark’s 1974 classic, Black Christmas is undoubtedly one of the most beloved Christmas horrors, a bonafide slasher must-see and more often than not hailed as a true genre forefather, cementing the tropes we all know and love today. To phrase it simply, Black Christmas is an exceptional feat.

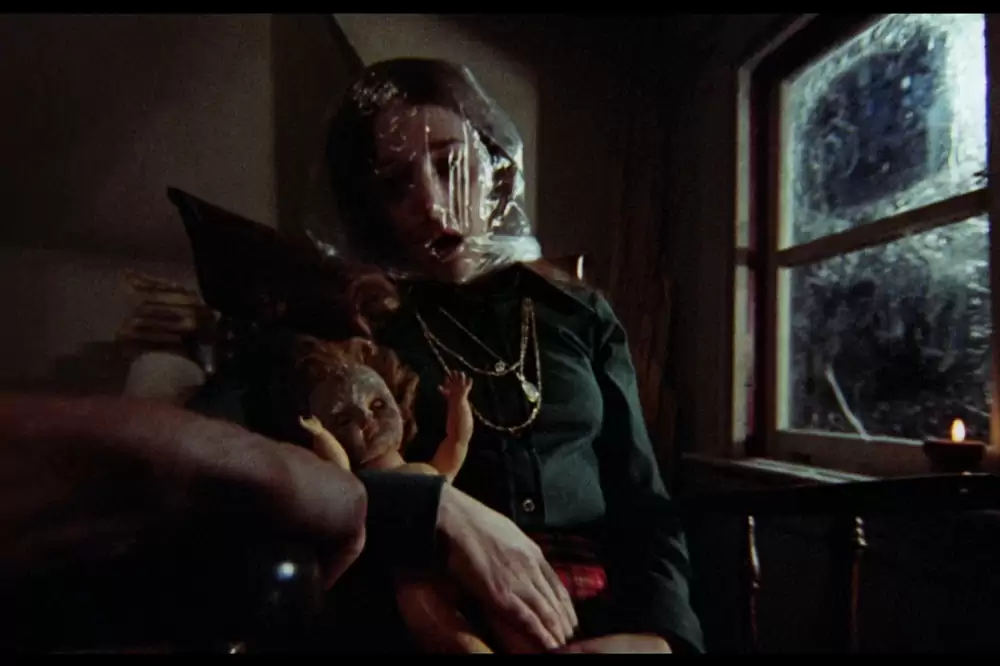

The chilling urban legend, often coined as “The Babysitter” or the more plot-revealing “The Babysitter and the Man Upstairs” is a campfire essential, the kind where a torch is held under the chin, creating ghostly shadows as the terrifying story bleeds out from the speaker. Its gravity is palpable, which Clark so impactfully captures within the plot of Black Christmas, based upon this iconic tale. Black Christmas opens with a Sorority house hosting a small soiree before the night is interrupted when Jess Bradford (Olivia Hussey) answers the phone to a disturbing caller, grunting obscenities. This is not the first time the unwelcomed caller has rung, earning himself the sorority-granted nickname “The Moaner”. Distressed by ‘The Moaner’s’ continuous threatening mumblings, student Clare (Lynne Griffin), retreats upstairs to pack for the upcoming holidays, however, she is soon suffocated to death by an unseen man lurking in her wardrobe. This first domino of Clare’s murder sets off a chain reaction of pure mayhem as the killer strikes again and again.

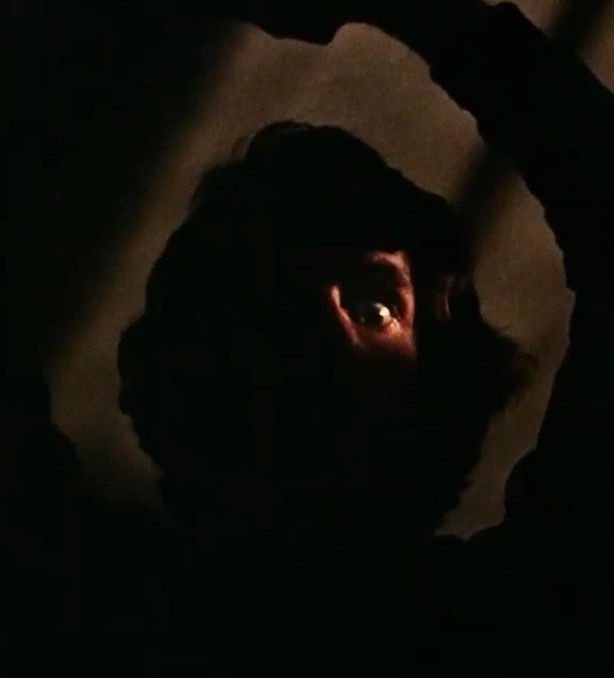

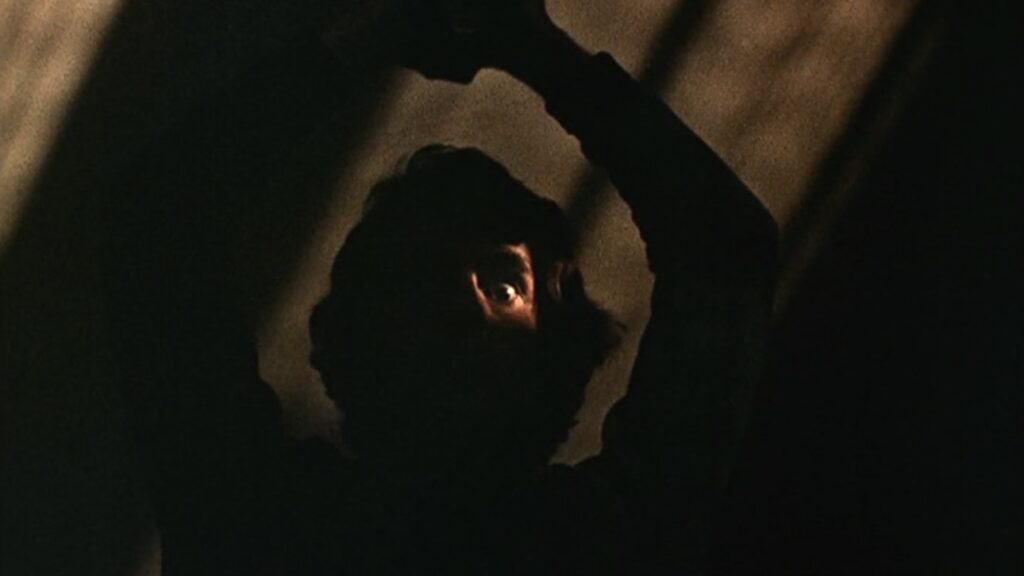

Black Christmas’ prototype-like properties for horror cinema vary from the intimate cinematography, all the way through to the ‘final girl’ theory. Beginning with the visuals, cinematographer, Reginald Morris continuously plays with the film’s voyeuristic tones, whether that be through the recurring point of view shots, or the positioning of the camera to show the characters from the perspective of ‘the other’; think of long drawn out shots of the camera peering at the characters through a window, or static scenes of a character going about their business, with the camera lurking from behind an object, replicating a prying, hiding gaze from an antagonistic force.

It is these sinister, foreboding visuals that were replicated in the likes of ‘Deep Red’ (1975) ‘Halloween’ (1978), and ‘Friday the 13th Part II’ (1981). Peeping into the privacy of others and watching in wait are common tropes that were not ‘invented’ from Clark and Morris’ work in Black Christmas, but it was one of the kickstarter’s that forged an unforgettable flame that remains to this day the initiator of some of cinema’s most terrifying scares.

Further elements that don Black Christmas as an iconic exhibition of genre cinema are its genuinely thought-provoking and intriguing politics that extradite the horror of reality and place it against an unnerving, tinsel-decorated background. Whilst the dramatic undertones have always been present within the reception that the film received, it is noticeable that over the fifty years (!) since its release, Black Christmas has been acknowledged as quite the feminist piece.

Professor Carol Clover cemented the idea of a ‘final girl’ in her 1992 book ‘Men, Women and Chainsaws’, with her work examining this idea of the surviving female in slasher films, a character that she describes as the one “who is chased, cornered, wounded; whom we see scream, stagger, fall, rise and scream again”. She is the one who lives to tell the tale, and in the case of Jess Bradford (alongside all the other established final girls), she is the catalyst that blurs the screen and the viewer personifies a sense of contagious empowerment and enforces a sense of active agency.

Latching onto this string of agency is the film’s exploration of bodily autonomy. A subplot of the film concerns Jess’ pregnancy and her possessive boyfriend Peter’s (Keir Dullea) reaction. Whilst Peter sings the positives of the situation and how the pair should settle down and start a family, Jess expresses her anxieties over the citation, leading to a receptive conversation about autonomy that is still ignited as a topic towards the film to this day. As such, Black Christmas is infused with an autonomy-tinged undercurrent that speaks to the entirety of the narrative.

To digress, the film was released one year after the landmark event ‘Roe v. Wade’ (1973), which by a Supreme Court decision dictated abortion should be legalised across the United States, formed upon the basis of the constitutional right to privacy. Incorporating a current subject into a narrative structure, only to forgo its significance is a disservice to the weight of whatever situation is at hand.

What makes Black Christmas still significant to this day is that Jess and Peter’s subplot did not fade into the midst, the story properly took hold of the matter and saturated its gravity into the film. For instance, Jess’ internal conflict is voiced with a maturity that does not deem her ‘irresponsible’ for wanting to terminate her pregnancy, nor bound to the patriarchy for wanting to keep the child. Black Christmas allows Jess room to breathe as a character, and to be morally multifaceted. The nuanced exploration adds a certain depth to the film that aids its transcendence as a true classic.

The slasher genre is ballooned with an array of treasured films including but not limited to: ‘Scream’(1996), ‘Friday the 13th’ (1980), and ‘A Nightmare on Elm Street’ (1984). Alongside this is a barrage of slashers that do not hold a flame to the key players, the ones that slipped through the cracks, and for good reasons why. To create a meaningful slasher there need to be the obvious, blanket positives across all films – a soundtrack with a dramatic flair that adds buoyancy to the tension, interesting story hooks that drop intriguing twists and turns, and a form of memorability that typically manifests within the main villain, often a masked, cunning and nefarious being. Black Christmas, ticks all of these boxes whilst still maintaining a unique, savviness that allows it to be a jolt to the expected elements, even on a contemporary watch.

Unlike the famed cloak-shrouded, claw-gloved, hockey-masked monsters of slashers (with goodwill, we here at Dead Northern are massive admirers of the mentioned villains), the primary antagonist in Black Christmas, later known as ‘Billy’ (Nick Mancuso), is largely physically unidentifiable, with his motives, nature and complexities also being concealed. Billy’s anonymity is a large part of the film’s disturbing nature, with him not only naturally gaining an omnipresent aura of terror, but also an air of uncertainty as to how his reign of terror is resolved. There is no unfolding backstory over the whole course of the narrative where bread crumbs can be left for his capture, nor is there a resolute understanding of what he wants, the end goal, and what can make him stop. He is a force of chaotic and sporadic violence that can taunt anyone and everyone.

The film’s conclusion nods to Billy still being on the prowl, despite the incessant ploys, fights and will to put an end to his madness. Billy’s unrelenting pursuit is demonstrative of Black Christmas’ legacy in cinema. The film marks the top of many slasher “listicles”. Its structure catalysed the subgenre that we know and love today. Black Christmas has spawned a desirable endowment to horror, with the film even spawning two further entries with the quintessential 2000’s ‘Black Christmas’ (2006), and the not as popular ‘Black Christmas’ (2019). Fans even joined together to make a mini feature titled ‘’It’s Me, Billy: A Black Christmas Fan Film’ (2021), which was followed by the sequel ‘It’s Me, Billy Chapter 2’ (2024).

Bob Clark’s masterly composition of a Christmas-themed slasher is a seminal work that has stood the test of time for fifty years, with its impact surely lasting many more decades. The film is an emotionally complex touchstone of precisely what a festive, bloodied yule-tide bonanza should be – dark, mysterious, contemplative and a celebration of all things horror.

Want more top horror lists and reviews? Check out our blog here..