Review- X (2022) – Ti West

Wayne (Martin Henderson) is a hopeful producer who casts his younger girlfriend Maxine (Mia Goth), and fellow actress Bobby-Lynne (Brittany Snow) to star alongside former marine Jackson (Scott Mescudi) in Wayne’s upcoming “dirty movie”, The Farmer’s Daughter. Joining them is director RJ (Owen Campbell) and his girlfriend Lorraine (Jenna Ortega). The group head to a rural farm in Texas owned by the elderly couple Howard (Stephen Ure) and Pearl (Mia Goth), who are kept in the dark about what the crew is shooting. Although Howard and Pearl’s unwelcoming reception proves to be tense, events soon turn much more sinister…

Ti West’s long awaited return to the genre is a stinging melody of psychosexual dread, fleshy fearfulness and enough tension to make those with nerves of steel clench their jaws. The A24 produced film fuses together multi-dimensional acting and a flawless sound arrangement to harness a bold take on modern-retro cinema and the intertwined wiring between horror and venereal subtexts.

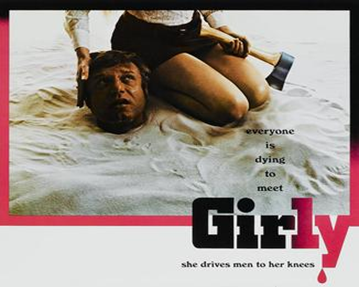

X thrives on a meta-commentative spectrum where West clearly pours out his devotion to the art of filmmaking itself. There’s the external level of self-referentiality via the characters being part of a production crew, going out to make a film in hopes of taking advantage of the upcoming home video market. Accompanying the obvious and very direct nods to the audience is the group’s discussion of elevating a niche genre movie to be a product of quality and the potential that independent cinema holds. Rather than just rely on overt dialogue to marry the borders between screen and reality and how the 1970s setting advanced a creative surge for exploitation across all media is the reintroduction of split screen, wide zooms, and swiping transitional cuts. These factors are reminiscent of seventies classics such as Black Christmas (1974) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1994) and still maintain a level of rarity amongst modern cinema, making these small touches noticeable, yet vital in bringing the viewer back in time.

The pastiche ode to a bygone culture makes the film the love letter to cinema that it is. West has long infused a certain level of passion into his films, with The House of the Devil (2009) and The Innkeepers (2011) lingering success being down to their unique portrayal of the nefarious horror that lurks amongst isolating souls and settings. Whilst the crystal clear loyalty to filmmaking is a crucial plot device, one of the more direct double-entendre strands is birthed from the film’s most ferocious element.

Hardcore porn is treated with an air of respect in X. West adds in the quintessential argument of morals thanks to a tense conversation between the holier-than-thou Lorraine and the rest of the crew, but overall the art of erotica serves as more than a cheap trick to lure in movie-goers and appease to the cliche that horror is just gory smut. It’s not a secret that horror has a long history of being taboo. Whilst heavy genre cinema still gets its premieres and mainstream releases, expressing a passion for horror still raises a few eyebrows to this day. X amalgamates the stereotypical lowbrow elements of horror and sex to conjure an artful expression of lust for life, bloodshed, and downright grizzly violence.

The weighty symbolism is both subliminal and full throttle mainly down to the absolutely riveting performances from every single cast member. Brittany Snow rips off that Pitch Perfect (2012) reputation to deliver a totally surprising parade, Scott Mescudi unveils his best performance yet, Jenna Ortega cemented her role as a future scream queen, Martin Henderson excels at the whole ‘everything is bigger in Texas’ vibe, Owen Campbell perfects the ‘awkward’ fish out of water role, and last but not least is Mia Goth in this career defining performance. X provides a stage to exhibit Goth’s immense talent and versatility as an actor. The entire aesthetic of Maxine is reminiscent of Linda Lovelace, another sex symbol from the decade. More significantly Maxine possesses this usually unattainable confidence that spares no prisoners and dares to be tested, fashioning a level of allure that makes the viewer both unsure and undoubtedly mesmerized by her assertiveness.

Whilst mimicking sleazy skin flicks holds a majority share in X’s growth, the cinematography is far from amateur. The brooding shots sweeping over the rural setting, as well as the slow motion scenes flourish stunningly within the slowburn narrative that allocates time specifically for director of photography, Eliot Rockett, to flesh out an eerie atmosphere that purposefully subverts our gaze and amplifies our curiosity. One particular scene masterfully raises the tension level through a bold overhead shot of Maxine taking a dip into a seemingly vacant lake. However, amongst the stillness in the swampy frame is a scaly alligator lurking right next to the unknowing Maxine. Whilst this reveal isn’t a spoiler, it does shed light on how West continuously diverts our attention and misdirects where the presumed violence is going to come from. The segment is a straight cut lesson on how to build a potent scare with no dialogue and soap opera dramatics.

Indeed, X has ample amounts of foreboding cinematography, bountiful performances, and unmissable set design, but one area that really rips into the visceral nature of the story is the hard hitting soundtrack. Audiences will definitely find themselves bopping along to well known tunes and the not so subtle “bow chicka wow wow” music that accompanies The Farmer’s Daughter scenes. Welding the score to the more grounded texture of X is the cover of ‘Oui Oui Marie’ by Chelsea Wolfe, whose rendition of the dainty cabaret-esque 1918 song saturates the film with a gritty, dusty tonal expression. It’s just another one of the countless ways West dovetails the film’s neo-grindhouse influences throughout every single vessel.

X has already achieved a warm welcome from frequent horror watchers and hard to please critics. And it seems that the film’s legacy has only just reached the surface as West is already in the editing phases of ‘Pearl’, X’s prequel, which will follow Howard’s disheveled wife and how the cabin was occupied as a boarding house during the first war. As if this wasn’t already a surprise to fans, West has also revealed that he has begun writing the third film which will chronologically follow the events unfolding after X’s ending. Whilst this is pretty big news considering X was released less than weeks ago, the slasher sub-genre does adore adding a string of sequels.

X truly is the full package! Whether it’s the narrative arcs descending into touchy allegories surrounding death, or if it’s the sheer gory pandemonium X has it all, making it not only one of West’s most impressive films to date but also an unmissable soon to be classic.

Looking for more top horror lists and reviews? Check out our blog here..