Top Ten Must-See Troma Movies

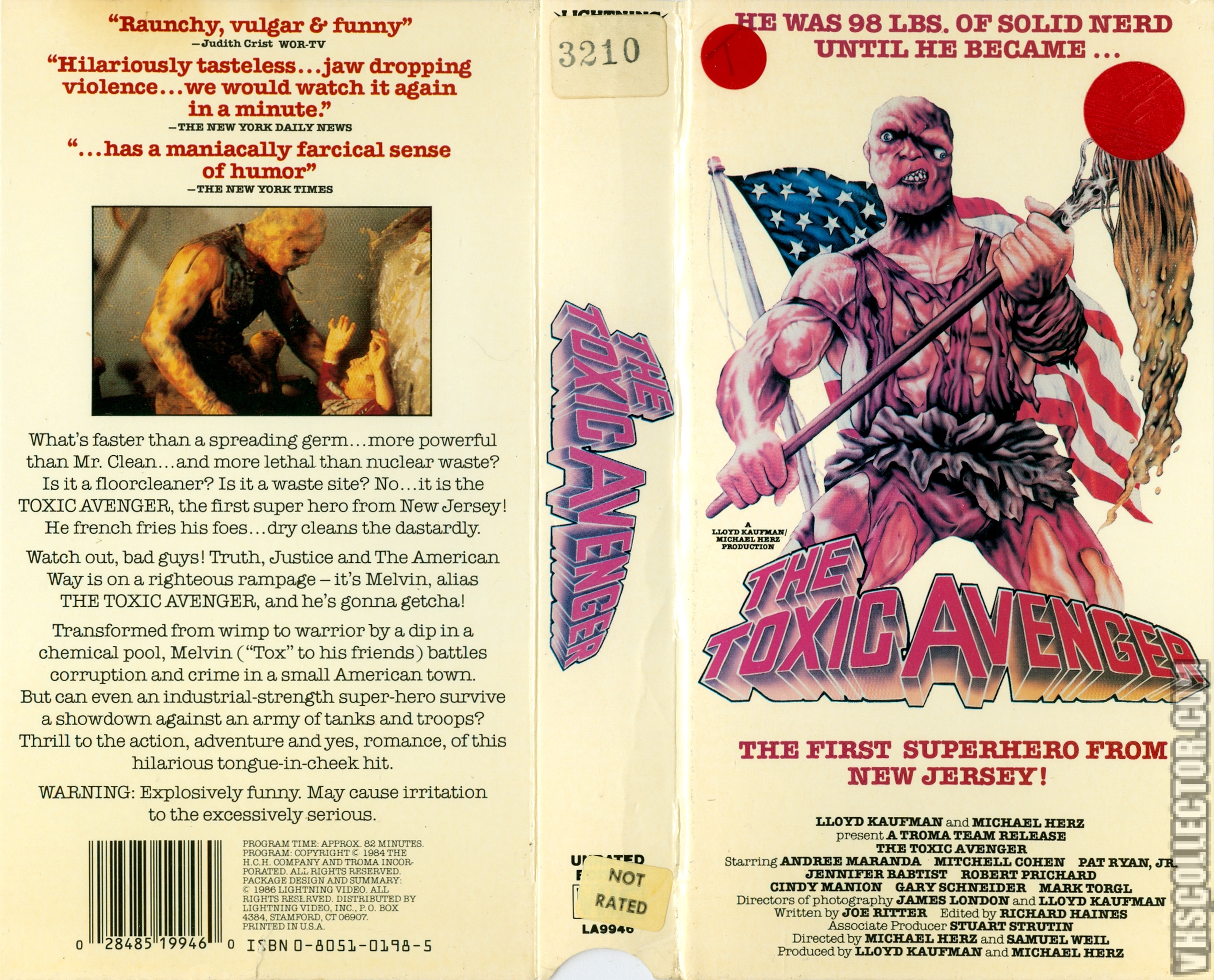

1- The Toxic Avenger (Directed by Michael Herz & Lloyd Kaufman, 1984)

A measly nerd (Mark Torgl) residing in New Jersey finds himself transforming into a ginormous monster after falling into a barrel of toxic waste.

If there was one singular film totally synonymous with the entire Troma legacy, then the film at hand would be The Toxic Avenger, the key to the company’s legacy and long-lasting success. The basis of the film’s existence came about in quite a typical fashion for Troma; Kaufman got wind that horror movies were apparently ‘no longer popular’ after reading an article at the Cannes Film Festival. So, with a boost of gumption and an upcoming production company backing him up, Kaufman and Herz concocted the idea of a swampish monster who would take on a hero persona to tackle those up to no good. The 1980s mainstream media would constantly belittle the horror genre, but Kaufman and Herz’s efforts were still met with solid reviews, leading to flocking audiences desperate to see this weird and absurd creation. Over time, The Toxic Avenger has built an entire franchise running behind it, with comic books, sequels, tv-series, a range of merchandise, and an upcoming reboot directed by Macon Blair and starring Peter Dinklage, which is due to be released later next year.

2- Combat Shock (Directed by Buddy Giovinazzo, 1986)

Frankie Dunlan (Rick Giovinazzo), a war veteran who fought in Vietnam is living in despair with his argumentative wife and deformed baby. The gritty poverty that he lives in, along with his less-than-perfect home life forces him to lose touch with reality and descend into insanity.

During the golden age of Troma came Combat Shock, a wild, wacky, and enthusiastic exploitation flick directed by Buddy Giovinazzo. Even those completely unfamiliar with Troma will probably have heard of Combat Shock being thrown into filmic conversations every now and then, primarily thanks to its nihilistic, drastic take on wartime history, particularly the Vietnam War. Whilst, Giovinazzo is certainly not the first filmmaker to tackle this important world event, he is however one of the only creators who have depicted such events in a radically chaotic and torturous way.

3- Cannibal! The Musical (Directed by Trey Parker, 1993)

A man on trial for cannibalism tells his story of how his deeds all went down through songs, performances, and dramatic flashbacks.

This cannibalistic, flesh-frenzied, meat-eating musical is nothing short of completely trippy. It was slightly based on the true story surrounding the self-confessed ‘Colorado Cannibal’ Alfred Packer, the film boards gruesome, grizzly visuals, epic settings, and surprisingly uplifting songs to create a film, unlike anything anyone would ever expect. Director and writer duo Trey Parker and Matt Stone (Now known for creating South Park) originally came up with the film’s premise for a project for a film class where they had to compose a trailer. The short garnered a lot of attention, encouraging the pair to raise a tidy budget of $125,000 to shoot a full-length movie. After the project wrapped and editing was complete, Cannibal! The Musical did not get a general release. However, in 1996 Troma saw the grave potential in the darkly spirited musical and picked it up. Over the years, Troma considered the film to be one of its best releases, even including it in the 2008 launch of the ‘Tromasterpiece Collection’.

4- Father’s Day (Directed by Astron-6, 2011)

Ahab (Adam Brooks) becomes hellbent on seeking revenge on the man who murdered his father.

Although Troma has its ties with the 1980s slasher hit Mother’s Day, 2011’s aptly named Father’s Day holds no relation to the classic; instead, this extravaganza is much more obscure, depraved, and downright hilarious. Father’s Day is directed by the team known as Astron-6, composed of Adam Brooks, Jeremy Gillespie, Matthew Kennedy, Steven Kostanski, and Conor Sweeney. The collective is responsible for must-sees such as The Void (2016) and Psycho Goreman (2020). Similar to Cannibal! The Musical, the film was conceived as a short film, but demand would take over, with the eventual full-length feature premiering at the Toronto After Dark Film Festival where it would receive a whopping total of 8 awards, including Best Film, Best Director, and nearly every Fan’s Choice award going. It’s difficult to pinpoint just one of the many reasons why the film is both one of Troma’s best features and a standout Grindhouse-like film, but a starting point is how far Father’s Day is willing to go whilst still remaining quick-witted and comedic. Throughout the violent journey expect plenty of mutilation, decapitations, and incest.

5- Terror Firmer (Directed by Lloyd Kaufman, 1999)

A maniac killer is out on the prowl at the same time as a film crew is shooting a low-budget feature in New York. To stop the madman on his path of destruction the crew bands together, resulting in tons of bloodshed and chaotic mania.

Grimy b-movies including Peter Jackson’s Braindead (1992) and Michael Muro’s Street Trash (1987) are distinct setups for that niche subgenre of horror that often gets overlooked and downgraded as total schlock. Terror Firmer understands this critical reception and uses it as a blueprint to create the most gnarly and gross-out b-movie to ever grace Troma’s books. The film was birthed by Douglas Buck, Patrick Cassidy, Kaufman, and James Gunn, and was based on the autobiography book written by Kaufman and Gunn titled ‘All I Need to Know About Filmmaking I Learned from The Toxic Avenger’ (1998). This gory voyage utilises the meta trend that soared through cinema during the late 1990s, setting the perfect scene for gruesome kills and humorous quips throughout.

6- Tromeo and Juliet (Directed by Lloyd Kaufman, 1997)

Filmmaker Tromeo (Will Keenan), falls head over heels for Juliet (Jane Jensen), the daughter of his rival.

William Shakespeare’s tragedy, Romeo & Juliet is an embracing tale of forbidden love, battling families, and the tortured fate of life without romance. Troma’s Tromeo and Juliet is an ‘interesting’ adaptation of the said play, except it follows a much more alternative route, depicting violent bodily vandalization and explicit phallic fantasies. Across the board, Kaufman’s vision may not be to every individual’s taste, but it is certainly a feast for Troma fans, with James Gunn’s script steeping the film in nightmarish scenes that dare the viewer to keep watching throughout all of the madness.

7- Class of Nuke ‘Em High (Directed by Richard W. Haines, Michael Herz, Lloyd Kaufman, 1986)

A group of students from Tromaville High mutates into hideous freaks after toxic waste finds its way into their water supply.

In the same lines as The Toxic Avenger, Class of Nuke ‘Em High is one of Troma’s most defining hits, with four sequels following (one [Return to Return to Nuke ‘Em High AKA Volume 2– 2017] even premiering at Cannes Film Festival). And just like The Toxic Avenger, this film acts as a loose sequel, also being based in Tromaville and being soaked in visceral, green sludge that makes every violent act even more audacious. Adding to the genre-defying theme are the electric-like sci-fi elements including the threat of nuclear plants, radiation fears, bodily mutations, and dominating creatures–all commanding the screen, creating a lingering fandom that refuses to stop.

8- Citizen Toxie: The Toxic Avenger IV (Directed by Lloyd Kaufman, 2000)

The Toxic Avenger (David Mattey) arises once again to save Tromaville from his evil counterpart The Noxious Offender.

Troma is rife with sequels, prequels, trilogies, and entire franchises. And out of all of these continued films, one of the best has to be Citizen Toxie. Just like the original–The Toxic Avenger–Citizen Toxie has plenty of bold gravitas and a keen sense of what Troma fans adore, tons and tons of madness. Quite impressively, the fourth installment features some stellar cameos from the likes of Eli Roth, Stan Lee, Corey Feldman, and Lemmy from Motörhead. Similar to nearly every Toxic Avenger film, the lack of societal correctness is a deliberate strategy to both provoke the comfort that resides in mainstream cinema and to create a film that soars past what anyone could possibly expect.

9- Blood Sucking Freaks (Directed by Joel M. Reed, 1976)

Magician, Sardu (Seamus O’Brien), kidnaps a string of people to use for his magic show. Little does the audience know that the torturous tricks are actually real.

Blood Sucking Freaks is possibly one of Troma’s most controversial films, and that’s saying a lot considering some of their other titles include Chopper Chicks in Zombietown (1989) and Surf Nazis Must Die (1987). Joel M. Reed’s nightmarish extravaganza was picked up by Troma in 1981, where they would make certain cuts to the film to receive an R rating, however, the version they ended up releasing depicted extremely graphic content, leaving no stone unturned through every scene, even including visuals of botch amputations, head crushing, teeth-pulling, and healthy doses of general torture. Of course, the censor board was not happy with the release of such content, but like with any cult classic, this made Blood Sucking Freaks all the more fun.

10- Poultrygeist: Night of the Chicken Dead (Directed by LLyold Kaufman, 2006)

A fast-food restaurant is taken over by zombie chickens after the building was constructed over an ancient burial ground.

If the name of Kaufman’s 2006 feature doesn’t give you enough information already, Poultrygeist: Night of the Chicken Dead is a demented, unreal, and shockingly absurd descent into mayhem. In the essence of true independent filmmaking, the film was made possible by the pure devotion to the cinema, with Kaufman and Herz partially self-funding the film just to get it made. Along with this, most of the crew were volunteers who were fortunate enough to see the adverts on Craigslist and other messaging boards looking for a pair of extra hands to help out on a film set for a legendary production company. However, this hard work wasn’t in vain as the film was a rip-roaring success, with its reception making it a firm favorite for Troma fans.

Looking for more top horror lists and reviews? Check out our blog here..

![Tromeo & Juliet [Blu-ray] [1996] [US Import]: Amazon.co.uk: Lemmy: DVD & Blu-ray](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81Oc3wtimkL._AC_SL1500_.jpg)

![Friday the 13th Part III – [FILMGRAB]](https://film-grab.com/wp-content/uploads/photo-gallery/thumb/Friday_the_13th_Part_3_061.jpg?bwg=1569591410)