The lens of folk cinema captures the evil beneath the soil that haunts the land and infects those who rebel against it. Those unfortunate souls who dare taint the grounds suffer greatly, leaving devastation in its wake and causing hysteria and havoc amongst worried souls, simultaneously cultivating rich growth for the horror in lore, myth, and legends. It is an alarming yet alluring ethos that propagates the success of folk horror.

Over the years, folk horror has seen a significant boom in popular horror cinema, with the likes of The VVitch (2015) and Midsommar (2019) and the equally successful but far more underrated Kill List (2011) and The Ritual (2017). With these films holding supreme status in modern horror, a deep dive into the origins of the folk horror subgenre has never been more pertinent.

Where to begin…

Folk horror holds its roots in nearly every country. It isn’t easy to pinpoint a specific religion that holds the key to folk cinema, with the genre belonging to many cultures. Folk derives from folklore, translating to individualised mythology from various societies. What has become known in mainstream media as ‘folk horror’ with all of its iconography and archetypal symbolism is, at the crux, derivative from British lore. For example, the bones of folk horror that audiences have come to know and love today are birthed from Pagan rituals; it’s the profound meaning of life and death, the cycles of nature, and the importance of worshipping a higher power that amalgamates with the genres eerie rhetoric that provides such influential works.

The Unholy Trinity

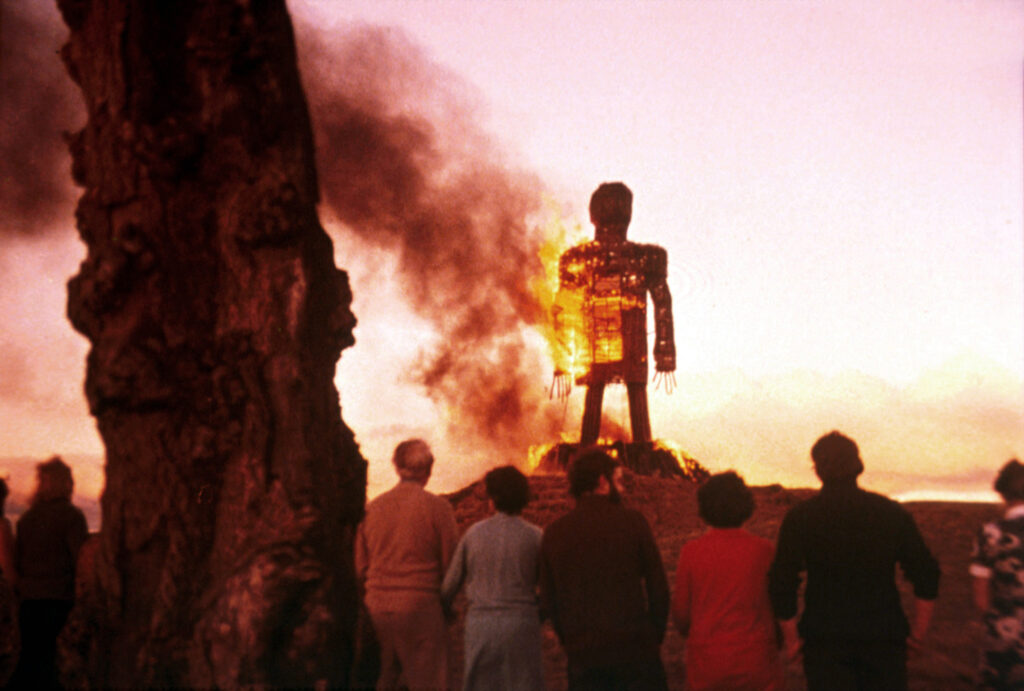

Every reign of horror has its champions. Folk horror’s genre-defining entries can be found in The Unholy Trinity, consisting of Witchfinder General (1968), The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) and The Wicker Man (1973). Mark Gattis first coined the term in the BBC docu-series A History of Horror in 2010, which was soon adopted as the official definition of folk horror’s primary instigators. Each entry into the Trinity is entirely unique and somewhat different from one other despite their blanketing together (which can be quite the metaphor for how broad the scope is on folk cinema).

Michael Reeves’s Witchfinder General chronicles the self-appointed witch-hunter Matthew Hopkins (Vincent Price), following his misdeeds throughout small rural villages across East Anglia. The cruel barbarism that follows in the wake of Hopkin’s actions creates a structure that can only be described as a mob-like ruling where sovereignty is not earned and equally placed but instead stolen by whoever holds the most power. Witchfinder General depicts Hopkins as he storms in and does not simply command authority but instead takes it from his victims.

British folk horror storylines thrive in the social divide seen in the likes of Witchfinder General; the films allude to how the most significant threat does not strictly adhere to paranormal entities and ghoulish ghosts; instead, it’s the same civilisation that one belongs to. This essence of fearing your fellow neighbour and evil lying within the home is further explored in Piers Haggard’s The Blood on Satan’s Claw.

The motivations behind much of the folk horror seen in the mid-1970s surrounded the hippie counterculture that dominated the landscape during that time. The decade saw a rise in young people declaring a belief system that went against the common consensus. They protested the war, dabbled in the increasingly popular substances arriving in the common market, and openly expressed the desire to change the system. The Blood on Satan’s Claw follows a group of young people in a small village being overcome and possessed by the devil himself after a skull is found underneath the town’s ground.

The cult of demon-worshipping children is shown infiltrating and recruiting other members to the group until eventually banding together to cause ultimate destruction. The film can be easily read as an on-screen recreation of the disharmony that was arising at the time, with the notion of sudden societal uproar being one of the critical themes of the film.

Out of the trinity and the entire catalogue of British folk horror, one of the most crucial, successful, and effective films has to be The Wicker Man. Robin Hardy’s classic follows the residents of Summerisle as they complete a ritualistic sacrifice for the land to ensure a fruitful harvest. The Wicker Man remains the most influential folk film and one of the most important horror films in general across British cinema. Throughout the film, the main character is Summerisle. It’s a symbolic living and breathing organism that devotes itself to the people, and in return, the residents nourish it with sacrificial flesh, blood and bones.

Beyond The Unholy Trinity

Amidst the horticulture of the well-renowned Trinity was a string of TV specials that have become ingrained in the thesis of British folk horror. Television, possibly more so than cinema, is entirely reflective of its audience. Britain is known for its blunt and bleak outlooks and humour, meaning that much of the fictitious media to come from the country relies on the nation’s unique nihilistic framings.

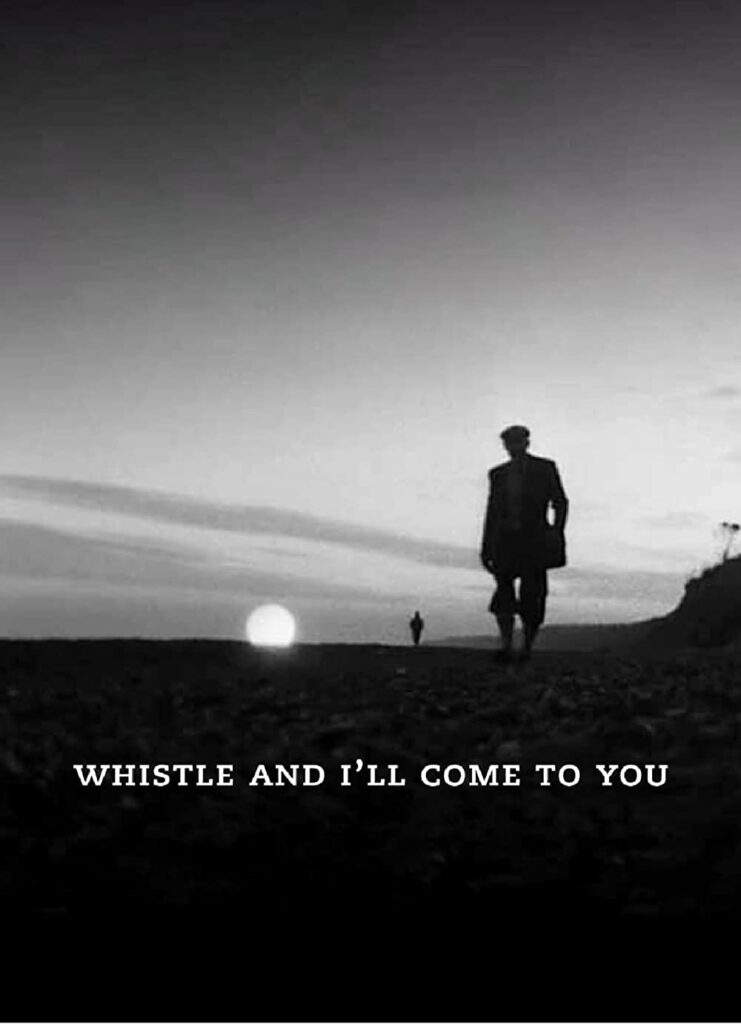

Whistle and I’ll Come to You (1968), Penda’s Fen (1974) and Red Shift (1978) are just some of the many television specials that captured Britain’s gloomy atmosphere with the traditional folkloric spirit. With these television specials also came a form of notoriety that allowed folk horror to be available to a broader audience than film allowed. When speaking of the times, not everyone had the time or ability to go to the cinema and view these fantastical folk films. However, many had access to a television set where these spooky entries would interrupt the standard Saturday night entertainment specials to display the most tempered and sinister of frights.

It was a time of paranoia, with the events in the news being scarier than any film or book anyone could have ever witnessed. With this, a level of immunity was stripped back, children would walk past paper stalls with the sinister headlines in full sight, and the daily news report would blare on the radio over breakfast. The presence of these shows was momentous. It was a chance for ghastly stories to enter the home and invade the keep calm and carry on attitude. Folk horror uses the presence of rural locations, familiar faces, and supposedly ‘quaint’ bonds as a vessel for actual, brutal disharmony to break through. The prettiest village harboured the most terrible secrets; ancient curses lay underneath the silent fields, and the longheld family unit could be disrupted anytime.

Today’s context

Folk horror has never been more alive. The messages and symbolism seen in the likes of the Trinity still resonate from a contemporary perspective. For example, The Wicker Man is celebrating its 50-year anniversary this year, yet its connotations are more significant now than ever. With every harvest, the Summerisle residents must offer a human sacrifice to appease the ground’s thirst. In its rawest form, the film’s discourse surrounds how society’s actions profoundly affect earthly structures; the soil beneath us is not forgiving and requires care. Similarly, if we take a look at the whole Trinity, the entire pathology of every film can be sourced back to how the ecological landscape holds great power, and with great power comes a right to respect.

This aspect of the Anthropocene is and will always be a landmark in understanding folk horror. The relationship between land and human intervention is at the heart of many folk entries. As The Wicker Man implies, the people no longer live on Summerisle as simple occupants. They are intrinsically connected to the land. They must offer a sacrifice; otherwise, their well-being will wither with the ground beneath them.

Legacy

Folk horror has birthed an entire subset of movies. Even films that do not necessarily fall into the lines of folk horror weaponise the standard folk format to convey its harrowing message. Take, for example, In the Tall Grass, the 2019 horror based on Joe Hill and Stephen King’s 2012 novella. The film implies that crops hold some form of supernatural power over those who dare to step foot on the land. Even The Blair WItch Project (1999) has a folkloric undertone, with the group of explorers being purposefully misled in a forest due to a presence that controls the woodland. Akin to nature itself, folk horror is everywhere, it’s inescapable and has never been more potent.

Want more top horror lists and reviews? Check out our blog here..