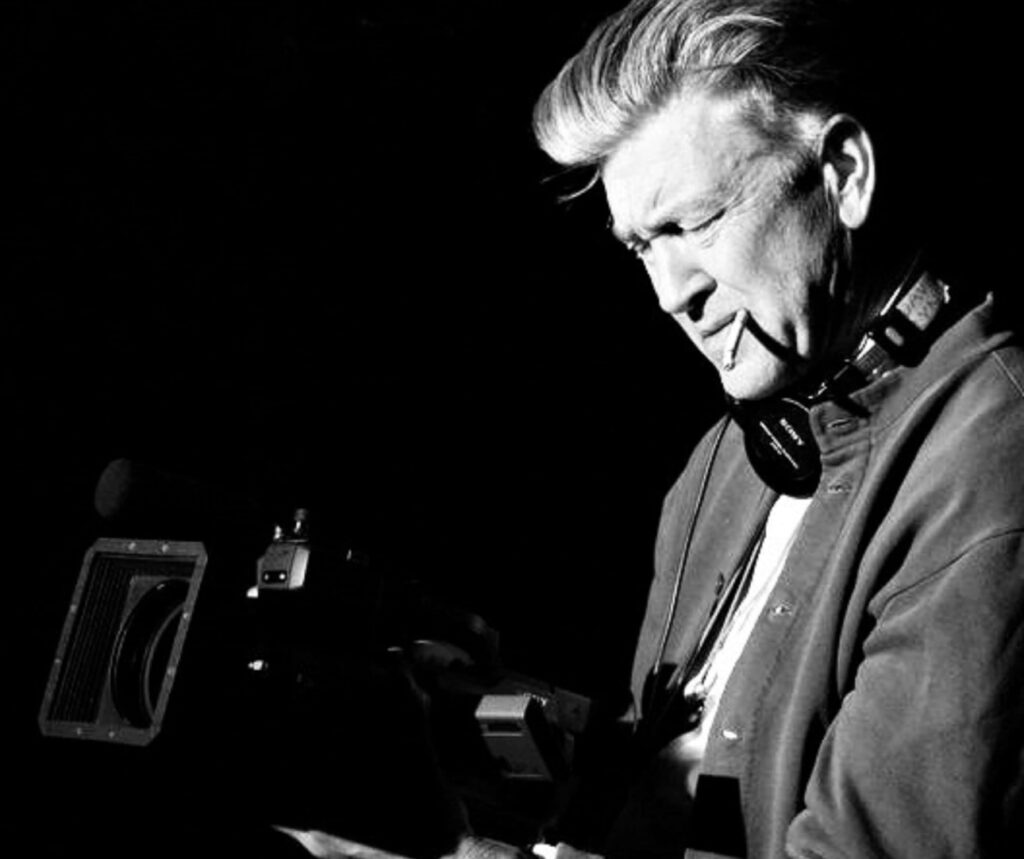

A Tribute to David Lynch

The great David Lynch, filmmaker, musician, artist and actor, recently passed away on the 15th January, 2025, leaving behind an extensive legacy as one of cinema’s finest auteurs.

Over the years, Lynch had become a forger for all things strange, dark and fantastical, with even his surname become synonymous with surrealism within the arts. His eclectic views of the world are often shown throughout his work like a beacon, with each of his efforts, whether that be in film or various other strains of media, exuding tremendous amounts of creativity and emotion, harbouring a unique sense of absurdity and magical realism throughout every piece.

The roots of his art formed from his youth where he grew up in quite a middle class environment, the picture-perfect idea of the ‘American Dream’. However, it was during this period where he noticed that behind the veiled harmony was a darkness in everything and everybody, with Lynch often using a nature-themed metaphor to describe his analogies. Although he was surrounded by lush greens, trees with ripe fruit and sunny rays reflecting onto the scraping paths of grass, the ground underneath was still littered with biting red ants, the dropped fruit would often rot and the cruelness of life still wormed its way into the quaint territory.

This harsh and deep method of thought would follow his career, spanning countless short films, features, music videos and more.

The Shorts: Part I

Having harnessed his admiration for a career in the arts, Lynch enrolled at the ‘Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts’. It was here where the soon-to-be director would make his first short film titled ‘Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times)’ (1967). The short was just as esoteric as the name suggests, with the film showcasing six distorted figures kinetically regurgitating on screen to the sound of high-pitched visceral noises. The film screened at his art school’s annual exhibition, where he won joint first place. In attendance at the exhibit was H. Barton Wasserman, a wealthier student who offered him a sum to direct another film to be screened at Wasserman’s home. Lynch proceeded to spend half the fee on a camera in hopes of progressing from amateur to a semi-professional level of practise, however, the end result of his project was essentially a blurred mess.

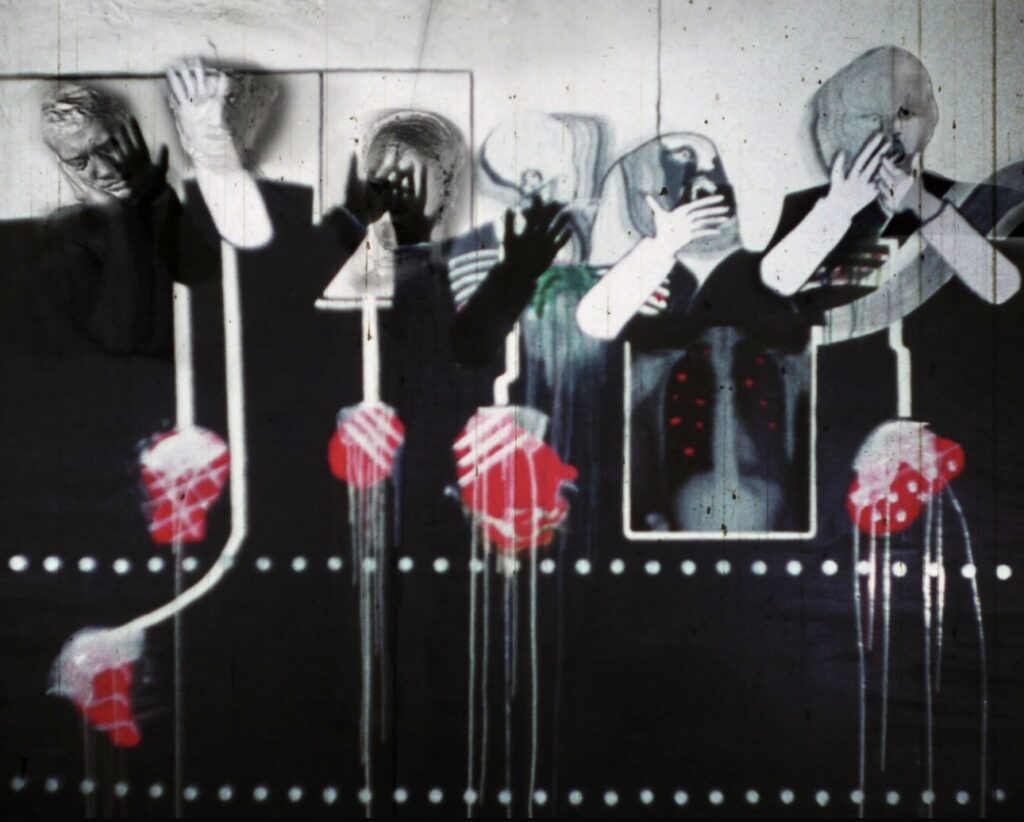

Despite the initial result, Wasserman waived the project and let Lynch use the remaining money to create whatever the budding creator wished, leading to the short horror film, ‘The Alphabet’ (1968). This mixed media project used both animation and live action, following a young woman singing ‘The Alphabet’, complete with a visual rendition of what can only be described as the wretched confused messes one experiences in the most horrid of night terrors.

At the time, the now infamous ‘American Film Institute’ (AFI) was still finding its feet, offering small grants to filmmakers, in turn helping the organisation grow. As such, Lynch submitted The Alphabet, along with a script for his future short ‘The Grandmother’(1970), his longest project at the time, spanning 33 minutes of runtime. Successful in his application, Lynch began production on The Grandmother, which would follow a young child who plants a seed, eventually growing a grandmother as an escape from his parents abuse. Once again combining a mix of live action and animation, the short baffles, with even the AFI openly informing Lynch, that although brilliant, the short cannot be categorised and defines the idea of ‘form’ itself.

Prompted by his mentors at the AFI, Lynch was urged to apply to the organisation’s ‘Center for Adavnced Film Studies‘, to which Lynch would once again successfully gain a place at the prestigious conservatory. Now in L.A at the conservatory, he wrote the script for ‘Gardenback’, another short based on a painting of his, but due to continuous interference by the school over the outcome of the film, Lynch would make a defiant step and leave his scholarship behind. In a bid to save who they believed was their best student, the AFI dean pleaded with Lynch to stay, to which he agreed, but only if he could make a film that was his and his alone, no interfering or shenanigans. This project would be ‘Eraserhead’.

Eraserhead (1977)

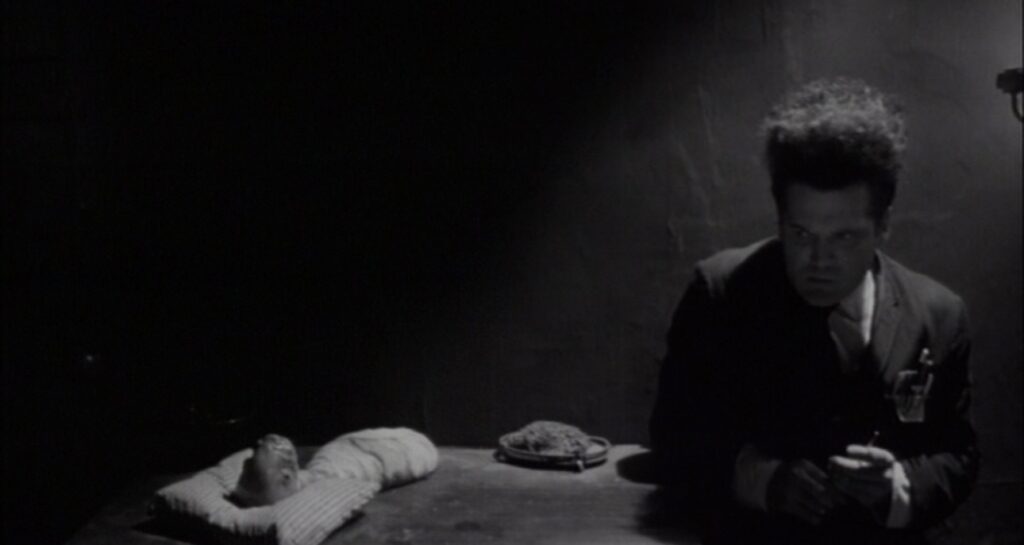

Just as any viewer of the classic hit would expect, Lynch’s feature debut was based on a daydream that he once had. Further influenced by Franz Kafka’s daring insect novella, The Metamorphosis (1915) and Nikolai Gogol’s short piece ‘The Nose’ (1836), this daydream turned feature would become Lynch’s ‘big break’ that would forever put him on the map.

The film follows factory worker Henry (Jack Nance), whose bleak life in an industrialised barren land spirals after he discovers that his depressive girlfriend Mary (Charlotte Stewart), has given birth to a dysmorphic being. Eraserhead is torturous in its ways of unsettling, as the film refuses to comply with any form of normality, opting to defy logic at every corner. The extremely surreal landscape and turn of events is met with some of Lynch’s most disturbed imagery, particularly in the sequence where Henry decides to ‘unswaddle’ his newborn, revealing an array of visuals that can only be described as a hybrid between mashed roadkill and alien-like substances.

The torrid displays are met with a layered emotive texture that figuratively captures the anxieties of fatherhood in a time of disarray. Although difficult to confirm, it is rumoured that the film’s central thesis concerns Lynch’s own anxieties about being a young father to his daughter, Jennifer, particularly whilst residing in a squalid neighbourhood. Lynch took inspiration from his time living in downtown Philadelphia with a young family when writing Eraserhead. Lynch has often commented on that time as being genuinely scary, with the high crime and drug rates making time outside, or sometimes even in, his apartment a dangerous environment. This idea of unneasy atmospheres combined with a unique tinge of body horror/anxieties towards otherness is a premise that continued long after Eraserhead into the rest of Lynch’s career, particularly in his following feature ‘The Elephant Man’.

The Elephant Man (1980)

Before reaching mainstream success, Eraserhead soared in the underground circuit, generating masses of attention, leading to a screening at the BFI London Film Festival (1978). Having seen the trippy exploration into madness, Stuart Cornfeld, an executive associate for the legendary actor, director and writer Mel Brooks, urged Lynch to collaborate on his next project. Lynch originally put forth the idea for the unfinished film ‘Ronnie Rocket’, but after realising that the film was not financially viable, he opted to directly ‘The Elephant Man’, a film written by Chris de Vore and Eric Bergen, telling the true story of Joseph Merrick. The study of Merrick proved to be an emotional one, with the man’s story being one of utter heartache and injustice.

The Elephant Man follows Merrick, who as a child was injured and left with facial disfigurements. Twenty or so years on and in Victorian London, Merrick has been the central attraction in a circus called ‘The Elephant Man’, showcasing Merrick’s injuries as a cruel sideshow. What begins as a tale of shock becomes a heartfelt exploration into the depths of humanity, revealing Merrick’s merits that were stripped from him for so long. The film, whilst certainly being a classic tearjerker, is a marvellous experience that captures the oddity of human beings, not necessarily through Merrick, but through the actions of those around him. To no surprise, the film was an abundant success, winning the hearts of critics and viewers, even receiving a whopping eight Academy award nominations.

The Elephant Man continued the pattern that Lynch often earned himself. Upon the success of his direction, the film’s buzz caught the attention of studios who would offer him future projects. His potential next step could have been ‘Return of the Jedi’ (1983), which George Lucas urged Lynch to take. However, Lynch openly declared his lack of interest. The offers continued to role in, with one particular offer peaking his interest, an adaption of Frank Herbert’s sci-fi novel ‘Dune’ (1965).

Dune (1984)

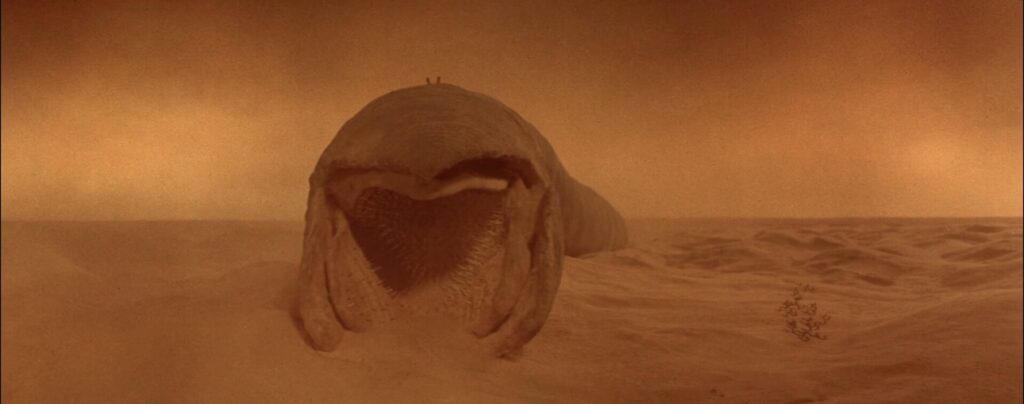

The 1965 novel had been in developmental hell for nine years, unable to reach production. Just as the film rights were about to expire, producer Dino De Laurentiis and his business partner/daughter Raffaella De Laurentiis had decided that they finally found who would bring Dune to the big screen. Upon contact, Lynch admitted to never having even hearing of the book, but after reading the novel, he admitted his new found adoration for the sci-fi story.

The film takes place in the late future, circa 10191 in the desert planet Arrakis, where the spice ‘Melange’ is the most treasured commodity. In a bid to prevent the forces who seek to control Dune’s resources, young heir Paul Atreides (Kyle MacLachlan) leads a treacherous rebellion to save the planet. Dune is a tricky film in the sense that it is baffling, which quite famously left many viewers downright confused as to what on earth they just watched. It seemed that despite the large budget of $42 million and the credentials of Lynch, Dune would be the first commercial downfall that Lynch experienced.

Prior to filming, the script had gone through several redrafts, with the reported number of final drafts being seven. Alongside this, the producers would also excise numerous scenes and add new sequences, leading to the final product being the convoluted project that audiences complained of. As with many rocklily received films, Dune did find itself with a small but strong cult fan base who have defended the film for years, keeping it in the spotlight all this time. Despite the niche status, Lynch has expressed his continued dislike for the film himself. In interviews over the years, he has commented that he felt that Dune was a ‘studio film’, one where his signature creative touch became lost. Admitting that he saw the film as a commercial opportunity to get his further ideas financed, Lynch has said that he ‘sold out’ on his intentions, letting the studio condense the plot into whatever they saw fit.

Although Dune could be viewed as the sore spot in Lynch’s otherwise stellar filmography, the film has seen a contemporary rise in interest, mostly due to the recent revival of the Dune world in the Denis Villeneuve directed adaptions.

Blue Velvet (1986)

Frustrated by the result of Dune and feeling like his cinematic roots had become tied to the commodification of commercial filmmaking, Lynch wanted to make a story that was personal and tied to his passion of surrealist cinema. The result of this call back to his early days was Blue Velvet. Similarly strained by the financial loss of Dune, the De Laurentiis Entertainment grouped decided to go forth with Lynch once again and make a film styled to the art of cinema rather than the economy of it.

The production of Blue Velvet resembled a playground for Lynch where he was left unsupervised and was able to let his imagination soar, creating a film so entrenched in experimentalism and bold absurdity that the effects of its madness are still felt to this day. The writings on Blue Velvet are continuously evolving with the film spawning countless essays and books on the film’s stunning yet mysteriously horrific story. Much of the dialogue concerns how the film is akin to one large dream that Lynch manifested onto screen, with the thematics ranging from critiques over middle class America, the damage left behind from the ‘Oedipal’ family, and the treatment of mental illness.

At first, Blue Velvet received a mixed reception, with many reporting outrage over the film’s provocative manner of emotion, particularly in the visceral sense and how it got under the skin and triggered an unprecedented level of uncomfortability. Ironically, this is the precise statement that also made others love the maddening narrative of Blue Velvet. Regardless of what side audiences sat, the buzz about the film made Lynch and his cinematic style a household name.

Amongst all of its various readings, a sentiment that remains as important now as it was upon its initial release, is the film’s use of music. On various occasions, Blue Velvet uses diegetic music against the backdrop of particularly violent scenes, where the characters are shown almost experiencing a musical interlude in between the chaos. For example, one scene shows the sadistic Frank (Dennis Hopper), kidnapping nightclub singer Dorothy (Isabella Rossellini), and college student Jeffrey (Kyle MacLachian), taking them to Ben (Dean Stockwell), one of his criminal associates. However, before the violent hurrah ensued, Ben performs an impromptu lip-syncing rendition of ‘In Dreams’ by the great Roy Orbinson. The scene takes itself seriously, being careful to not interrupt the sporadic tension of it all by parodying the preposterousness of it all.

The general mixed reactions of either love or hatred over Blue Velvet’s theatricality was not what was important, what mattered was that Lynch’s frankly bonkers approach to cinematic life was now back!

Twin Peaks (1990-2017)

Television producer Mark Frost had met Lynch for coffee, meandering over ideas for potential projects. They discussed the premise of a body washing up on a lakeshore, comprising the very first stages of a project titled ‘Northwest Passage’, which would soon become Lynch’s arguably most famous piece, ‘Twin Peaks’.

Twin Peaks follows the investigation led by FBI agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) who is sent to Twin Peaks, a small Washington town to uncover who murdered local homecoming queen, Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee).

Although the central plot surrounds the mystery of Laura Palmer’s demise, Twin Peaks was conceived as a partial soap opera where once the lives of the Twin Peaks residents were unravelled, the story would evolve into exploring the troubles of the townsfolk, just as much as uncovering Laura’s death. It was this idea of the ominous surroundings of Twin Peaks itself that granted the series its successful pitching to ABC Network. In fact, in expressing their idea to the network, they ran the pitch with just an overt idea and an image, rather than a fully fleshed out dissection of the narrative. The almost whimsical hope placed onto a simple idea was enough to titillate the executives and aid the envision of this uncanny, niche, disturbed drama that is beyond haunting.

The pilot episode was almost a film within itself, totalling a runtime of ninety-four minutes. The rest of the series took a similar approach with each episode being on average forty-five minutes long, which proved enough time to develop a deep lore surrounding the inhabitants of Twin Peaks. The first season ran for eight episodes, which is a stark difference between the second season which ran for twenty-two episodes, followed by a full length feature that acted as a prequel ‘Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me’ (1992), and lastly a long-awaited third season that premiered in 2017 with eighteen episodes.

The legacy of Twin Peaks is just as potent now as it was thirty-five years ago, with the series part of the cultural framings for surrealist media. Although the practice is standard for most television series today, Twin Peaks was one of the first shows that presented itself as a cinematic piece akin to a feature film. Much of this is owed to Lynch, along with Frost‘s specialisation in exhibiting the inner turmoil of the characters in an outward, expressive and eccentric way. Throughout the series, Special Agent Cooper experiences surreal dreams which are displayed as part of the narrative, leading to some truly strange and unnerving sequences that can only be done with such efficacy thanks to Lynch’s talents.

Wild at Heart (1990)

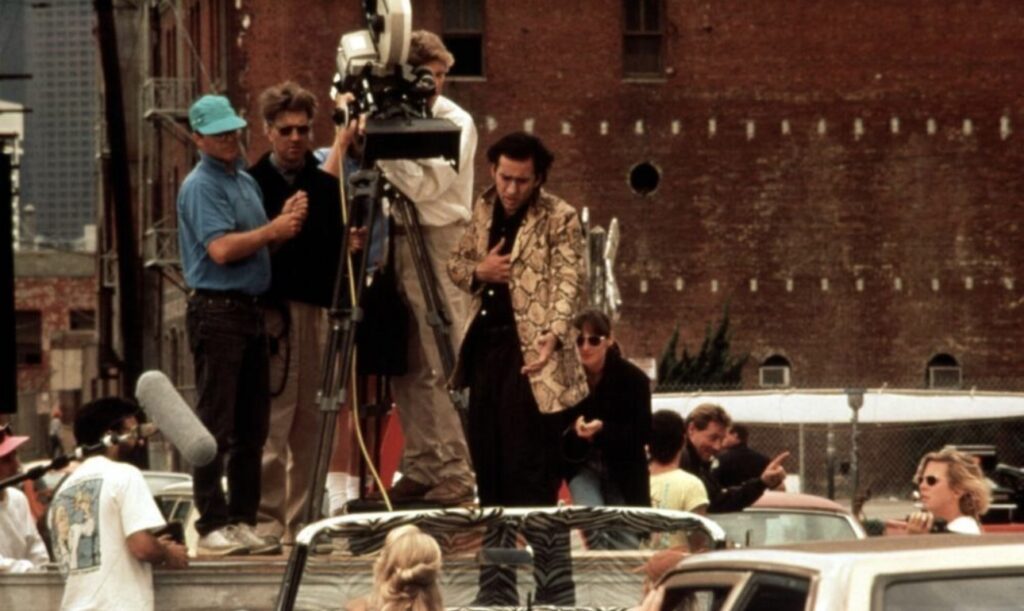

Whilst working on the first season of Twin Peaks, Lynch was gifted a copy of Barry Gifford’s Wild at Heart: The Story of Sailor and Lula (1990) by Monty Montgomery, a producer who wanted Lynch involved in his adaption of the book. However, rather than Montgomery behind the camera and Lynch producing, the roles were reversed, with Lynch once again being inspired to create something dark, passioned and zealous with life.

Wild at Heart follows Sailor (Nicolas Cage) and Lula (Laura Dern), a pair of star-crossed lovers who set out on a journey of violence and lust in an attempt to escape those who fight to keep them apart. Dingy motels, a 1965 Ford Thunderbird convertible and a killer soundtrack complete with Cage singing Elvis Presley songs is what makes Wild at Heart the beloved road movie that it is. There is a feverish zest to the film that is certainly in clear ode to Lynch’s ability to create the most dimensional of characters. Whilst the audience understand the ludicrousness of the love between Sailor and Lula, there is a quality so vigorous and infectious to their sprightly nature that it is impossible not to get lost in the wild journey they find themselves on.

The maddening hour or so we spent with the pair is one of the film’s most award worthy factors, with the jurors at the 1990 Cannes Film Festival also falling for Sailor and Lula, with the film receiving the prestigious Palme d’Or. Wild at Heart marked the first collaboration between Lynch and novelist Gifford, with the pair later creating ’Lost Highway’.

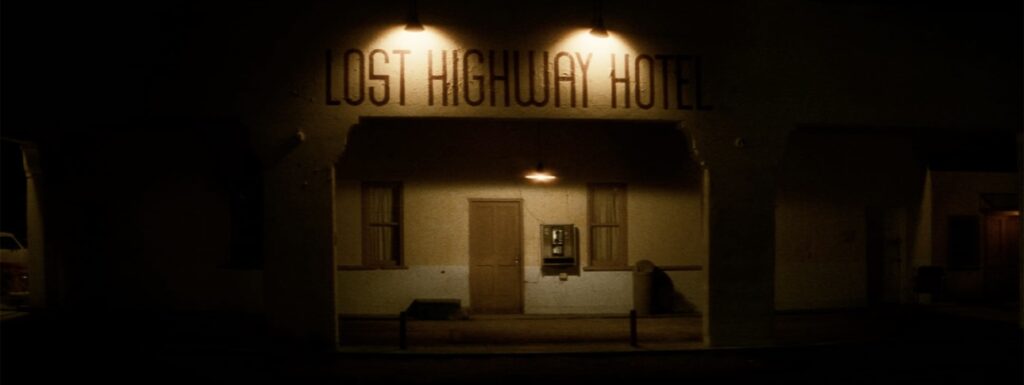

Lost Highway (1997)

Lost Highway, although not originally a Gifford novel itself, the writer used the intriguing term in his book ‘Night People‘ (1992). This phrase sparked something in Lynch, a feeling strong enough for him to contact Gifford and suggest that they write a screenplay together for a film titled ‘Lost Highway’.

The film chronicles a saxophonist (Bill Pullman) who begins receiving anonymous videotapes on his porch of him and his wife (Patricia Arquette). Soon after the strange occurrences, he is convicted of murder. Whilst incarcerated he goes missing and is replaced by a younger man (Balthazar Getty).

Describing the film as anything less than totally wacky, weird and quite creepy would be a disservice to the truly outlandish plot, with the film weighing heavy on the almost psychedelic side of filmmaking. The at times unexplainable plot has been advanced many times in scholarly literature, however, in accordance to Lynch’s statements about the film’s interpretation, Lost Highway is slightly void of full explanation. Lynch has expressed the film’s connections to themes of identity, but has ultimately commented that the film is flexible, abstract, a media installation that can be consumed without analysis.

The Straight Story (1999)

Unlike any other Lynch project is The Straight Story, a tale of determination and strength in light of hardship. It is not uncommon for even strong Lynch fans to not realise that this G-rated, Walt Disney Pictures film comes from the same mind as Eraserhead. Nevertheless, The Straight Story remains a testament to Lynch’s ability to create a complex, gripping and compelling film.

Written, edited and produced by Mary Sweeney, a longtime collaborator and once wife to Lynch. The film was based on Alvin Straight’s two hundred and forty mile journey from Iowa to Wisconsin in 1994, which was completed all on a lawnmower. Whilst the film is alien-like in Lynch’s filmography, this element becomes null and void when considering the beauty of The Straight Story. Every shot is akin to a dedicated photograph, with the heartiness of the story being permeated into each scene, whether that’s due to the exceptionally written characters or the stunning visuals that exemplify the beauty of the open road. The Straight Story really is a one of a kind.

Mulholland Drive (2001)

In the same year that The Straight Story was released to overwhelmingly positive reviews, Lynch’s idea for a new drama series for ABC titled ‘Mulholland Drive’ was rejected after disputes over the runtime. However, StudioCanal saw the potential that the show’s two-and-a-half hour pilot had, investing $7 million for Lynch to turn his television idea into a feature length film.

Similarly to Lost Highway, Lynch has expressed his willingness for the film to be interpreted as whatever the viewer sees, a rare suggestion from filmmakers who are usually seriously passioned regarding the meaning of their films. Yet, in typical Lynch fashion, anything is possible.

This open-ended film follows a newbie actress (Naomi Watts), who jets to L.A., where she befriends a peculiar woman who is suffering from memory loss after a car collision. What follows is a long string of vignettes involving a director (Justin Theroux) in the height of an industry conspiracy and a nightclub where seemingly nothing is as it seems. The most memorable aspect of the film, and possibly one of the most startling frights from all of Lynch’s work is the famous ‘Winkie’s Diner’ scene, where a man tells an acquaintance an urban-legend-like tale of a recurring nightmare where a sinister figure lurks in an alley waiting to kill. The pair decide to investigate and debunk the dream by venturing out into the alley, only to find that this frightening being really does exist.

The sequence is seemingly completely out of place and random, yet this startling moment encapsulates the entire motives of Mulholland Drive – nothing is as it seems.

The Shorts: Part II

Intent on creating, Lynch decided to return to his roots and create a series of short films on his own website davidlynch.com, one of the first entries being a mini animated series titled Dumbland (2002), complete with eight episodes all animated using a computer mouse and the basic Microsoft Paint package. Dumbland has a deliberately amateurish design, with the narrative following the monotonous routines of a dim witted man going about his daily rituals.

In the same year Lynch released Rabbits, another short that premiered on his website. Rabbits is one of Lynch’s more studied short series, with the eight episode web films showcasing a group of humanoid rabbits in their home. Rabbits takes the shape of a sitcom, but with an unbelievably horrifying twist.

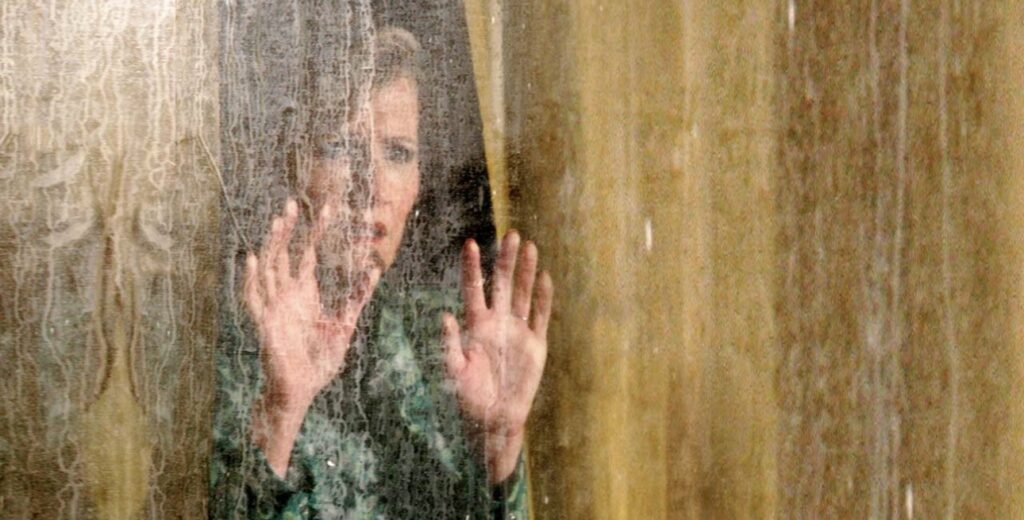

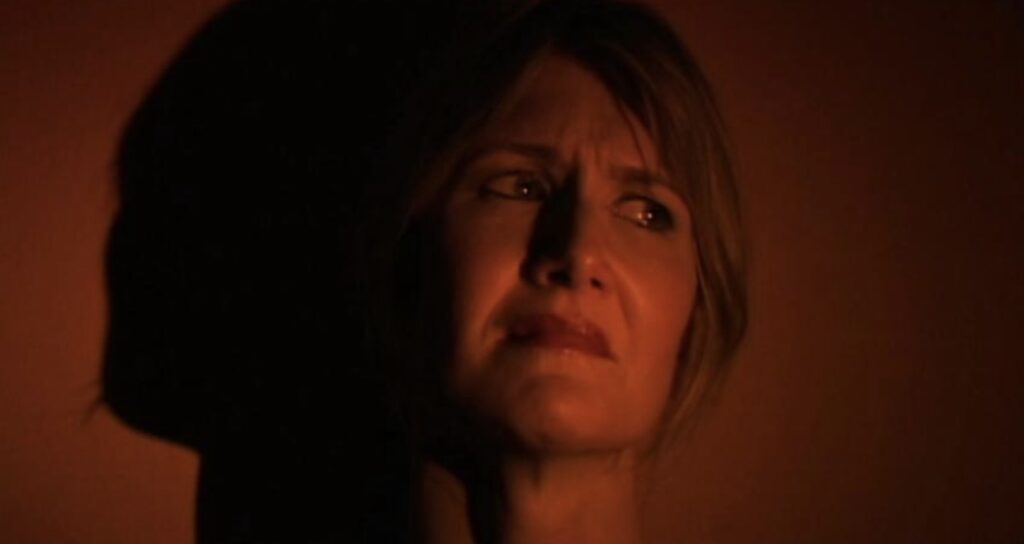

Inland Empire (2006)

The three-hour-long Inland Empire would be Lynch’s last feature film. The retrospectively acclaimed film follows the transformation that a Hollywood actress (Laura Dern) undergoes for a role.

Inland Empire has all of the traditonalities of a Lynch film, from the dreamlike story to a familiar cast, however, the film marks a series of firsts for the director. Rather than being filmed on Lynch’s preferred mode of film stock, Inland Empire was filmed using a handheld camcorder. The film also underwent production before the script had even been completed, let alone finalised and signed off, alongside this, the scenes were shot in chronological order. As a result, the film exercises its own motivations on the strangeness and ritualistic-like quality of filmmaking.

Much of the film explores the meta-like quality that performers go through in portraying a role, particularly the process of having to experience a fictional character, but nonetheless still having to express the character with an air of realism and authenticity. Although now nineteen-years old, Lynch’s final feature is an exemplary feat that is still as prominent today as it was years ago.

Want more top horror lists and reviews? Check out our blog here..