Abigail (Directed by Matt Bettinelli-Olpin and Tyler Gillett)

Abigail is part heist movie, part monstrous horror. A film of two halves. The first half plays on its own genre stereotypes and known ploys, lulling us into a sense of familiarity, before ripping the curtain back and unveiling an exhilarating ride that ceases to calm right until the credits roll. The film thrives in its fantastic performances by Melissa Barrera and Alisha Weir, who together add a depth of performativity that elevates the entire project. Abigail brings unprecedented levels of bloodied mischievous and anarchy to the screen, making Carrie’s prom meltdown (1976) or the blood elevator scene in The Shining (1980) seem like a papercut worth of gore. Abigail’s bountiful twists and turns, alongside the impressive scoring and unmissable performances, make this one of the best films of the year.

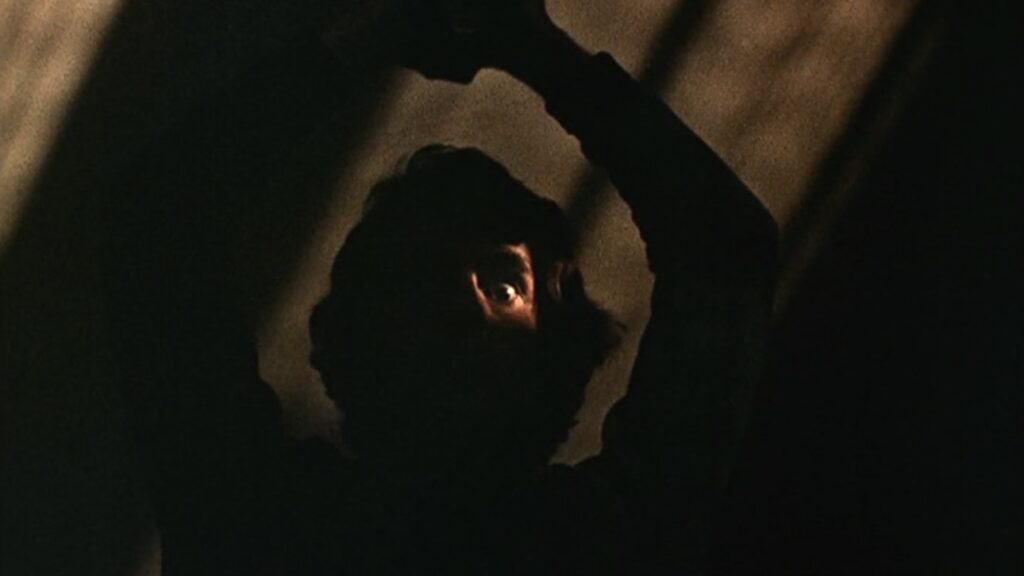

Longlegs (Directed by Os Perkins)

Longlegs epitomises fear, with the film exhibiting some of horror’s most frightening imagery to date, mainly in the form of the titular villain himself ‘Longlegs’ – a devil-worshipping man whose energy and appearance are nothing less than nightmare fuel. The enigmatic Longlegs is portrayed by the one and only Nicholas Cage, who enters into the uncanny role with a disturbed naturalness. Despite Longlegs’ strange appearance, the costumery of his garb, personhood and appearance is not entirely alien, with his expressions still resembling some form of a person. It is this precise aura of realism entwined with absurdity that makes Longlegs a film steeped in an uncanny atmosphere. Fantasticality combines with the monotonous every day to create a horror that lingers with the viewer long after watching.

Kill Your Lover (Directed by Alix Austin and Keir Siewert)

Kill Your Lover portrays deeply seeded toxicity within tainted relationships with a level of understanding and richness that is rare to come by. Exemplifying the portrayal of poisonous dynamics is the film’s stellar effects that take the form of body horror, combined with a touch of sci-fi-like venom and a hint of uncanny viscerality that is both gripping and distressing.

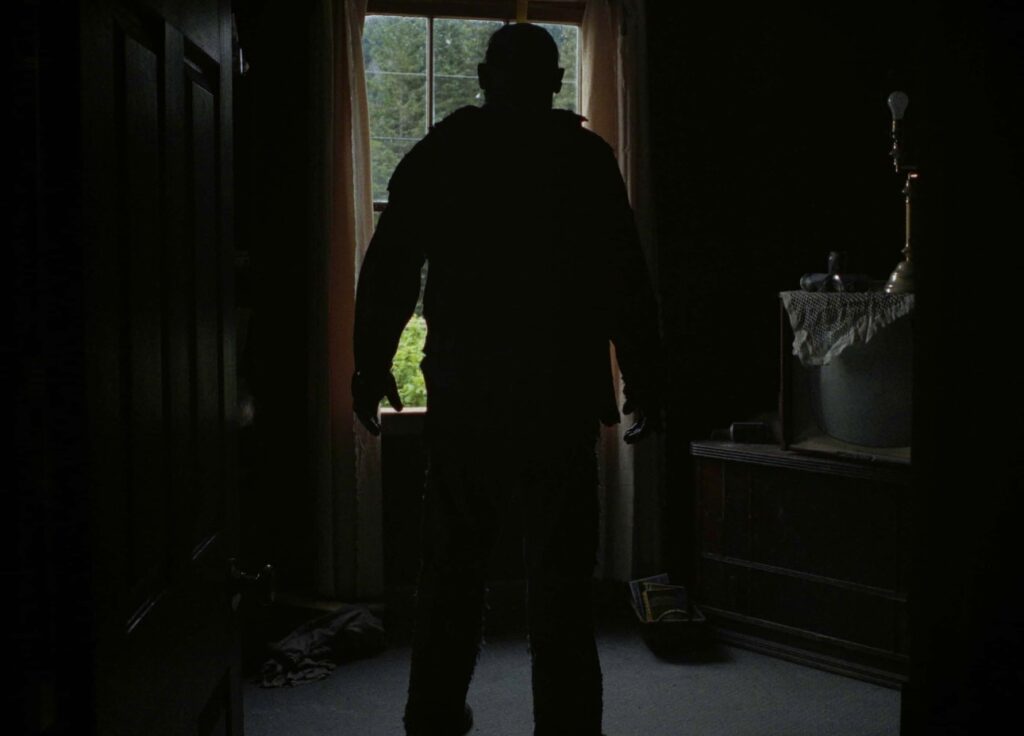

In a Violent Nature (Directed by Chris Nash)

Many reviews for Chris Nash’s feature debut commented upon the film’s slowness and its supposed style-over-substance approach. Perhaps the film is ambient-heavy and leisurely in its pacing, yet it is this precise unhurried, tender sense of built-up dread that makes the film the atmospheric, almost hypnotic slasher that it is. The switching of typical slasher perspectives and toning is both refreshing and satisfying, particularly when a plethora of truly gnarly kills are thrown into the mix.

Oddity (Directed by Damian McCarthy)

Damian McCarthy’s Caveat (2020) has one of horror’s most terrifying scares, which was so intense, freaky and suspenseful that it seemed the director had peaked. In no way could he top his own debut. However, not only did Oddity go above and beyond, it blew nearly every horror film out of the park with its shuddery, pulse-pounding frights that will have even the strongest of horror fans watching with the lights on (not that I am speaking from experience…). With the combination of an excellently spooky location, mysterious lore and a whodunit-like backbone, Oddity is bound to provoke one hell of a reaction.

You’ll Never Find Me (Directed by Josiah Allen and Indianna Bell)

This Australian horror brings new meaning to the word ‘tension’ as we are fed the plot bit by bit, with directors Indianna Bell and Josiah Allen opting for a painstakingly disconcerting breadcrumb approach. The entire film is one whole build-up to a disturbing conclusion, provoking an array of dreaded thoughts as we play detective in getting to the bottom of the film’s devastating conundrum. The drip-feed-esque terror is exacerbated by the film’s single location of a rural low-lit caravan, where the confined, desolate environment allows for the unnerving tension to be heightened to new extremes.

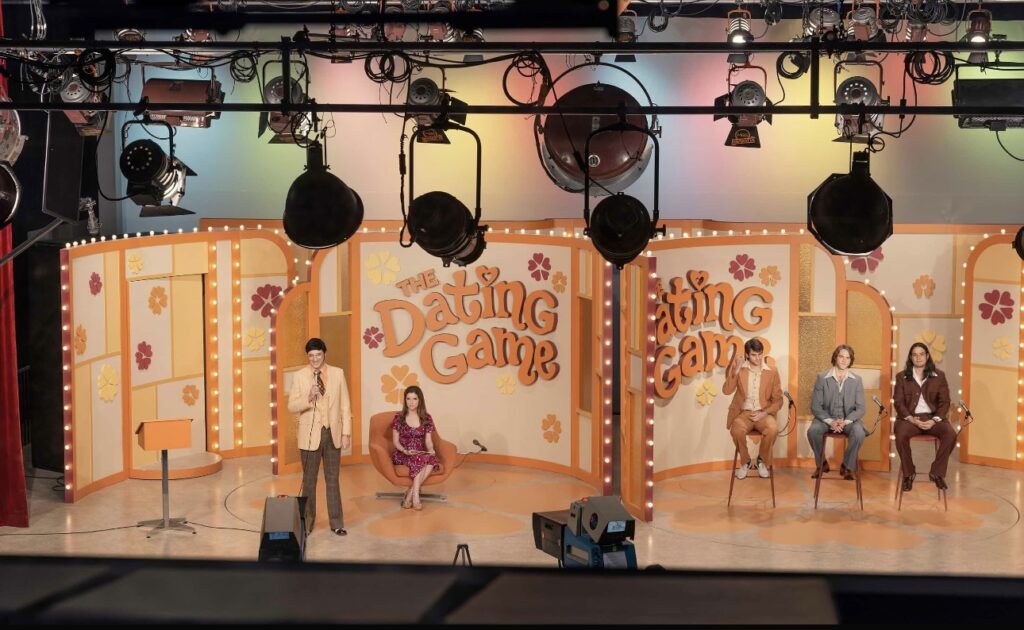

Woman of the Hour (Directed by Anna Kendrick)

Regarding the context of genre capacities, Woman of the Hour does not cast itself as a horror film, however, anyone who has bared the ‘parking lot’ scene knows that this anxiety-inducing story is a lesson in dark cinema. Actress Anna Kendrick is both in front of and behind the camera in this retelling of serial killer ‘Rodney Alcala’ (also known as ‘the dating game killer’ due to his winning appearance on a dating show). Despite the sensitive origins of the narrative, the film is not exploitative of the heinous acts of Alcala, with the film instead showing the true barbarism of his crimes. Kendrick is joined by actor Daniel Zovatto who portrays the slimy, wretched killer in all of his evil ways, which gives credence to him being a perpetrator, not an idol. Woman of the Hour is a crime adaptation done respectfully and rightfully.

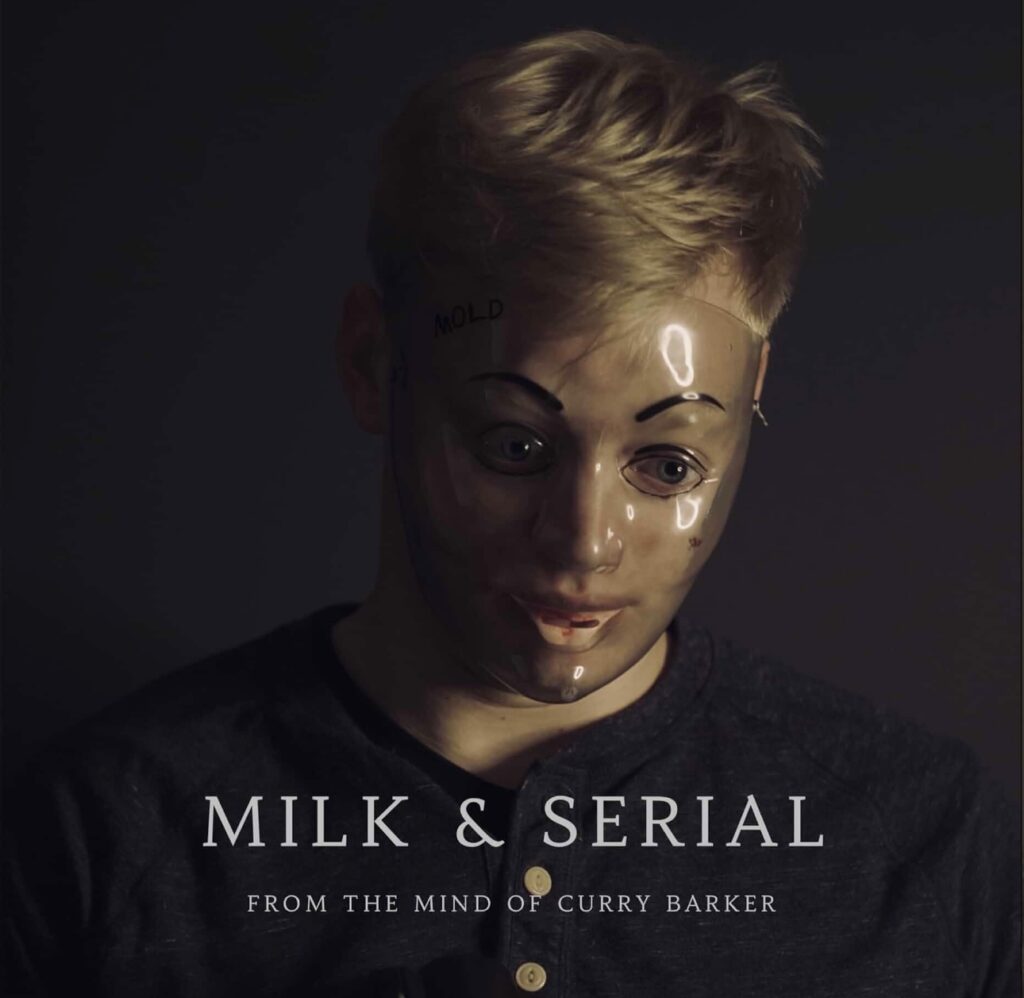

Milk and Serial (Directed by Curry Barker)

Milk and Serial is independent cinema at its finest, showing the capabilities of just an idea and a camera, forging large budgets, additional crew, expensive studio equipment and top locations. The film stars Curry Barker, who also serves as the writer, director, producer, composer, cinematographer and editor. This straight-to-YouTube horror appeared on the streaming platform via Barker and co-creator Cooper Tomlinson’s channel ‘That’s a Bad Idea’, which typically posts sketch comedy skits and short films. Part of the film’s effectiveness stems from its sporadic release. The only marketing was self-promotional posts on social media platforms from the likes of Barker, yet the film, which is essentially a long YouTube video, has amassed over one million views, alongside glowing reviews from major media outlets. Milk and Serial is a film replicating the new age of filmmaking that thrives in the grassroots approach to creating cinema that stands alongside wide releases.

The Substance (Directed by Coralie Fargeat)

Body horror has never looked so good in Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance, starring Demi Moore and Margaret Qualley. The Substance is powerfully symbolic in its thematics, with the film reflecting on the consequences of obsession and addiction over beauty, particularly the evolution of one’s beauty over time. These dramatic, figurative elements are unveiled slowly as the film unravels, with the conclusion piecing together all of the gruesome tidbits portrayed throughout the film, leading to a ghastly, heinous ending that is shocking, unsettling and marvellously sick.

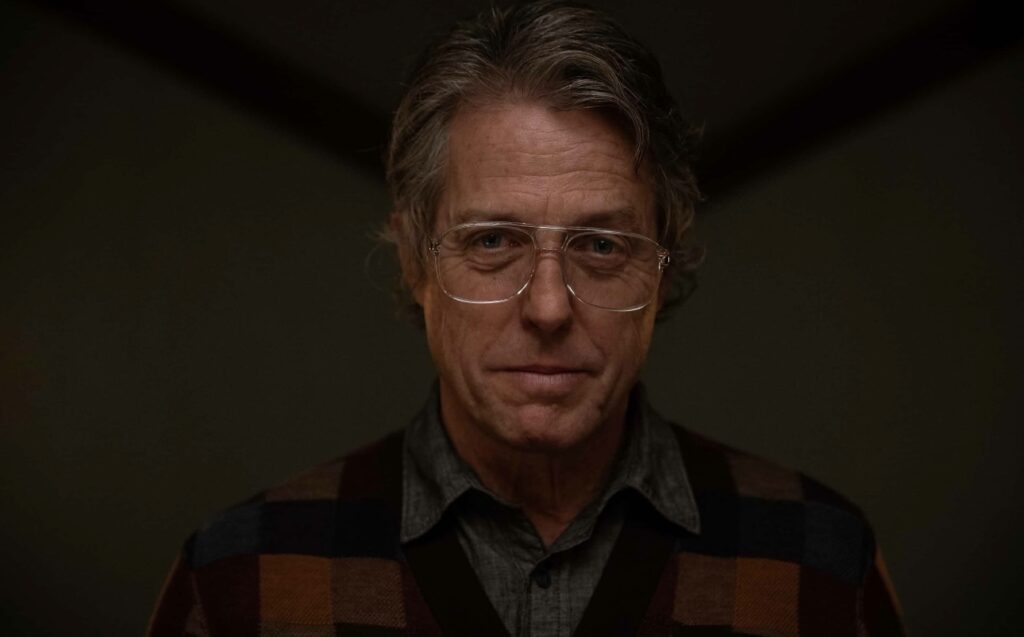

Heretic (Directed by Scott Beck and Bryan Woods)

Heretic stirs many questions that range from the philosophy of belief systems and religion to the strange psyche of the human condition. Yet the most prominent thought to arise from this provocative film surrounds Hugh Grant’s previous missed opportunities as a horror performer. If religious horror seems overdone, simply watch Heretic just for Grant’s unbelievably macabre role! Heretic’s cryptic narrative and uneasy atmosphere melt together to form a horror steeped in layers upon layers of mystery, chaos and hectic emotions that make it one of this year’s most interesting pieces of cinema.

All This Time (Directed by Rob Worsey)

All This Time is a unique spin on a gothic tale that thrives on a groundhog-like cyclical nature where the consequences of time enforce a sinister sense of being trapped within the most devastating and haunting of nightmares. The dreaded emotions of confinement and anxiety fuse and create a film that is a testament to independent cinema. All This Time is an enigma in every way possible, with the film being a true slow-burn right down to the bone.

Speak No Evil (Directed by James Watkins)

Christian Tafdrup’s Danish horror Speak No Evil (2022) erupted onto the horror scene like a fireball, picking up accolades and nothing but positive reviews. However, there was a collective eye roll when only a year later it was confirmed that there would be an American remake. Yet, by some strange turn of events, the remake surpassed every expectation and ended up being an excellent recreation. Speak No Evil nailed the excruciating frustration felt in the original, alongside the grand reveals and scenes of disturbed unease, all with a sense of originality that gives hope to the future of contentiously received remakes.

Strange Darling (Directed by JT Mollner)

Strange Darling is a remix of linear filmmaking in the best way possible, subbing a coherent narrative for something much more surreal, twisted and utterly absorbing in all of its complexity. Joining the feverish assembly of events is the film’s stylish aesthetics and looks that resemble the lurid, boldness of giallo horror, but with a neon spin, emphasising the daringness of the entire movie.

Cuckoo (Directed by Tilman Singer)

Hunter Schafer excels in this mind-warping horror that is akin to that of a contorted circus of outlandish disarray. The film’s overall composition resembles a kaleidoscope of terror, with the villainy of the film being so far-fetched and ridiculous that it makes the entire premise absolutely bonkers. Cuckoo is 102 minutes of pure devilish fun that will certainly hold up for many rewatches.

Late Night with the Devil (Directed by Cameron Cairnes and Colin Cairnes)

David Dastmalchian excels as late-night television host Jack Delroy, with the actor adding the necessary pizzazz and flair needed for such a forefront role. The film takes all of the best elements of occult cinema, from possessed youths through to religious cults, and dials them up to the max. Late Night with the Devil’s storytelling device is presented in the form of a lost broadcast from a fictional 1970s talk show, which makes for an immersive, gripping journey from start to finish.

Terrifier 3 (Directed by Damian Leone)

Everyone’s favourite clown returns in Damien Leone’s highly anticipated Terrifier 3, which is just as gory and stomach-churning as the rumour mill purported. The Terrifier films are brilliant because they do not know when to stop, they will just keep pushing the limit with each scene, with the third and latest entry being the most daring one yet. Complimenting the visceral experience is the equally as fleshed-out plot that continues with the lore developed in its predecessor, trickling a hint into the exciting future that Terrifier has to offer.

MadS (Directed by David Moreau)

MadS is nothing less than riveting, with the film being a single 90-minute long take with no breaks. The characters and events change and evolve, yet the camera does not take a single cut. Commenting from a technical point alone, MadS is a feat worthy of extensive praise, but director David Moreau refuses to rely solely on the sheer tactility of the one-shot approach, as the film is equally as wild through its tonality and plot points.

Red Rooms (Directed by Pascal Plante)

Quite possibly the most underrated gem of the year is Pascal Plante’s Red Rooms, a psychological horror that exposes the morality of obsession and the capacity of self-destruction to appease the curious mind. Where Red Rooms reaches its pinnacle of effectiveness is within its intelligent displays of the film’s central spectacle and how it handles a rich, broad issue surrounding the dark side of media.

Want more top horror lists and reviews? Check out our blog here..