Friday the 13th – genre-defining, monumental, and dare it be said, ‘totally iconic’. These are just some of the descriptors denoted to this mammoth of a horror franchise. With 12 entries to the series name, it can be challenging to define all of the films; however, amongst all of the slasherific and certainly unique films, there does seem to be an entry that repeatedly stands out. Joseph Zito’s Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter (1984).

A group of teens travel to Camp Crystal Lake for a weekend of debaucheries, but things soon go array when Jason Voorhees shows up to his stomping grounds to cause chaos. With this traditional storyline comes a shed of archetypal bloodshed where graphic kills and splatter-filled jumpscares dominate the screen. The Final Chapter is a bonafide classic, but it very nearly ceased to exist as Friday the 13th Part III (1982) was due to complete the Jason trilogy. That was until producer Frank Mancuso, Jr. became hellbent on killing off Jason once and for all. Mancuso worked on both Friday the 13th Part 2 (1981) and Part III, where it was widely reported that he felt his complex and crucial inputs as a production assistant and then producer were not taken seriously enough. In response to this, he recruited Zito, director of the 1981 slasher The Prowler to end the series under his terms. With this, Zito along with Manuso’s backing ended up conjuring one of Friday the 13th’s best films.

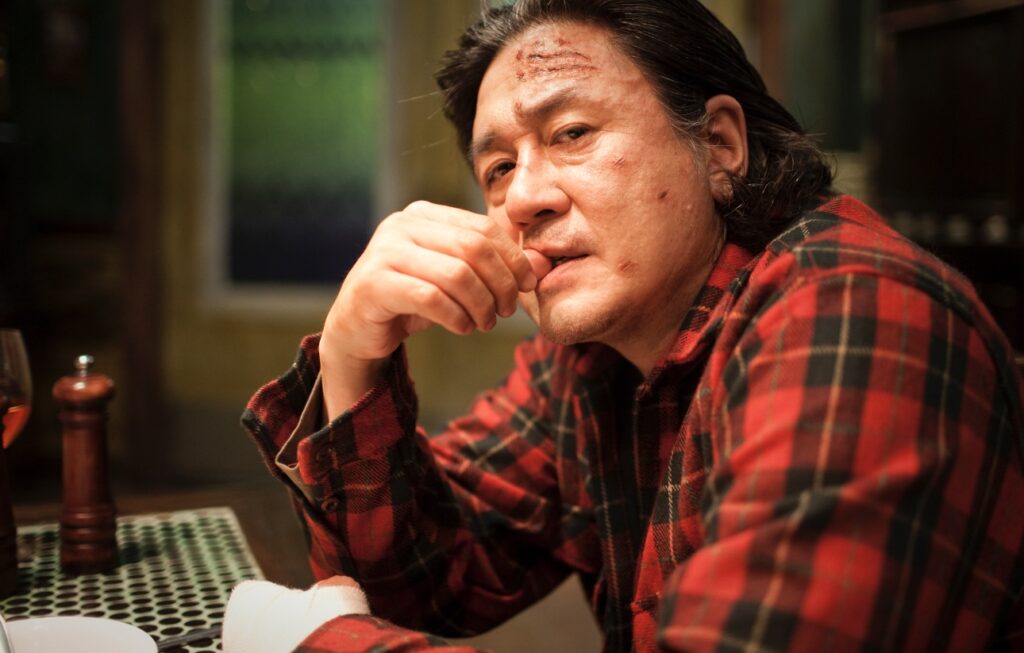

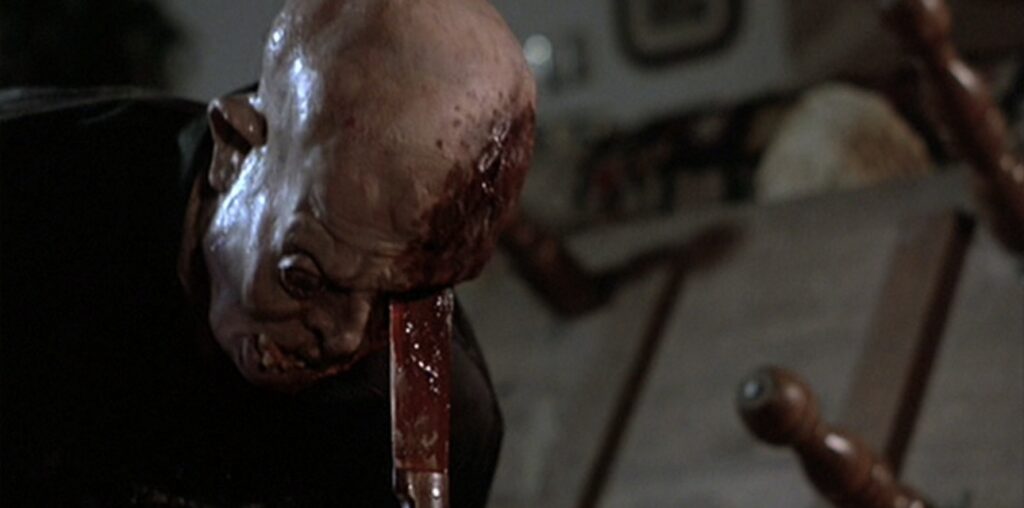

Complicit in this reputation is the film’s exceptional imagery that was made at the hands of legendary effects artist, Tom Savini. In The Final Chapter, Savini (known within the Friday the 13th universe for his visceral creation of Jason in the first film), tackled the likes of macheted necks, head twisting, pitchfork stabbings, crucifixion, meat-cleaver hackings and smashed faces. All of these were done with such vivid brutality that elevates the chaotic wildness of it all into genuinely intense, skin-crawling displays of pure depravity that show the brutish capabilities of Jason. Interestingly enough, the film’s evidential flare for the creativity of these depictions goes far beyond the surface, with the film’s primary protagonist having a spiritual tie to Savini.

Although The Final Chapter chronicles the aforementioned quintessential motley crew of youngsters dying at the hands of slasher’s favourite boogeyman, the film has an interwoven secondary line of narrative following the Jarvis family. Residing next door to the teens is Tommy Jarvis (Corey Feldman), his sister Trish (Kimberly Beck), and their mother (Joan Freeman), all of whom must face the wrath of Jason. Tommy’s ability to think on the spot and get inside the mind of Jason has allowed him to become somewhat of a staple member of the franchise, with his character starring in a total of three Friday the 13th films. Throughout his first appearance, Tommy makes quite the impression thanks to his eclectic personality. Tommy has an affinity for all things practical effects, making masks and prosthetics out of anything he could get his hands on, just as it is documented Savini did during his younger years.

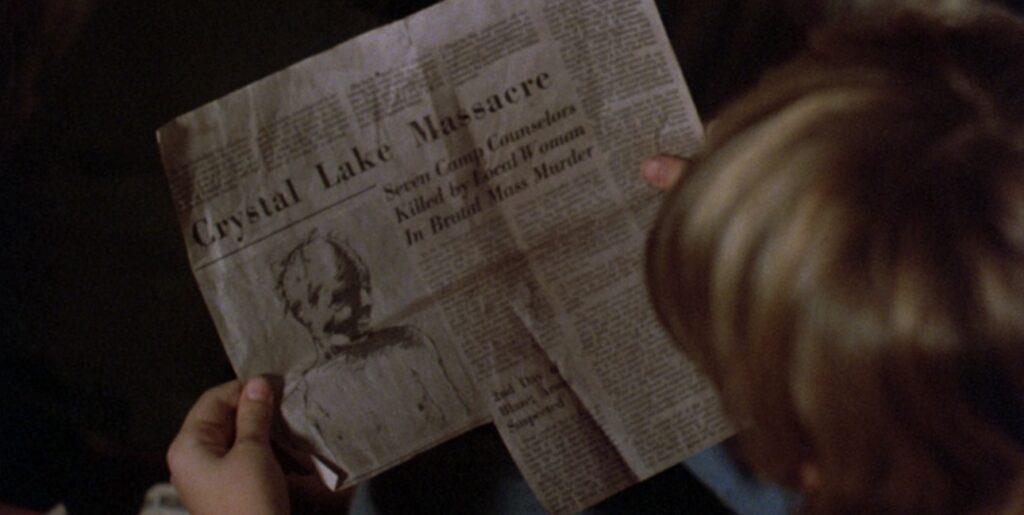

Tommy’s blossoming artistry and innovation is what beckons the film’s applauded conclusion. After copious events unfold, a hammer wielding Jason breaks into the Jarvis’, but just as he’s about to land a fatal blow on the terrified Trish, Tommy saves the day. It transpires that Tommy has found old newspaper clippings detailing Jason’s disfigured face and the horrid past that led to his vengeance. In a quick attempt to stir the psyche of the beast, Tommy hastily shaves his head, resembling a young Jason. Despite the grave risk, his plan roars triumphantly as Jason is captured and almost immediately gravitates with a childlike innocence towards Tommy, seeing his younger self alive and well. However, Jason’s fever dream is quickly interrupted as Trish brings down the machete to his head, knocking off his infamous hockey mask to reveal a horribly warped face before he stumbles to the ground as Tommy seemingly reaches madness and further pummels him into oblivion.

Tommy undergoes a terribly traumatic transformation to save the day. Essentially, he becomes one with the monster, which is only exaggerated by his rampant attack, overkill even, on Jason after the villain’s lifeless body flops to the floor. Prior to this scene Tommy discovers the tragic backstory that catalysed Jason’s descent; seeing this paired with his transformation of embodying the monster and then relishing in the demise all unleashes a beast hidden deep within Tommy that may have otherwise remained locked up.

The film’s finale sees Tommy stare blankly into the camera with a chilling coldness that mirrors Jason’s exact dispassion for human existence. The figurative expression towards Jason and Tommy’s symbiosis opens the film up to a world of possibilities that rings familiar to the first Friday the 13th’s retrospective analysis with all of its discussion about the horrors of maternal devotion. The Final Chapter is steeped in a seriousness that is not easy to craft as efficiently and naturally Zito has. The film still has that primitive nastiness to it that has horror hounds howling at the screen, yet the film is not one long novelty act that aims to solely appease the senses. It does not over extend its analytical gravity to the point of pretentiousness, but it is not afraid of baring its teeth and taking a bite into the critical details.

Even from a retrospective point of view, the film exercises a balance that is notoriously difficult to achieve; it creates a world of lore and backstory without over complicating and propelling the film away from its slasher roots that everyone has come to know and love. As of this year, The Final Chapter completes its 40th year around the sun, and yet, the film seems to have only gotten better. It has been a solid 15 years since the last Friday the 13th film was released. Considering that the next entry would be the ‘13th’ number, a possibly brilliant jumping step would be taking inspiration from the absolute fan favourite classic that is Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter…

Want more top horror lists and reviews? Check out our blog here..