Review – Late Night with the Devil (2024)

Late Night with the Devil sees the excellent David Dastmalchian as Jack Delroy, a 1970s

Censorship has consistently exerted a high level of control over what is and is not acceptable to be viewed. In particular, The British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) has made sure that horror has endured a string of scrutiny for decades, leaving a trail of irony, criticism, and controversy across horror history. The BBFC is the ruling authority that has been in power since 1912 due to the Cinematograph act 1909 which regulated what films were granted permission to be screened at the cinema.

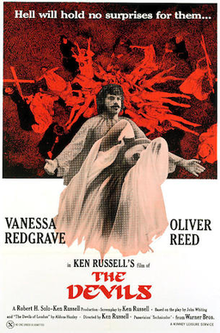

As time has progressed a series of changes has been made internally within the BBFC, with the primary alteration surrounding the changing role of the chief censor. At first, the BBFC was rather friendly with somewhat obscene material, as Chief John Trevelyan had a more open view of acceptability, take for example Ken Russel’s The Devils (1971). Trevelyan passed this film which was not shy about exposing sacrilegious imagery with an X rating. This soon transpired a series of outrage from the British Public. However, this brief enlightening of liberalization was harshly interrupted by the arrival of home video.

In 1979 video players were first released in all high street shops, available to anyone. Regardless of one’s age you could view any material no matter the content as film’s did not have to go through the rigmarole of censoring. In retrospect the introduction of this marvellous invention is ground breaking, yet many mainstream distributors were more than reluctant to release any films, as they saw it as a threat to cinema and piracy infringements. This reluctance aided an influx of low budget horror films to dominate the market. TV was no longer solely there to appease family values, instead it was a chance to watch lurid and explicit content without numerous cuts and interferences. The accessibility was viewed as a major threat to the “youth of Britain’s mental health”, as supposedly these graphic horrors could literally possess children and force them to repeat the acts that they saw on screen.

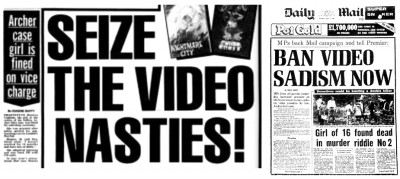

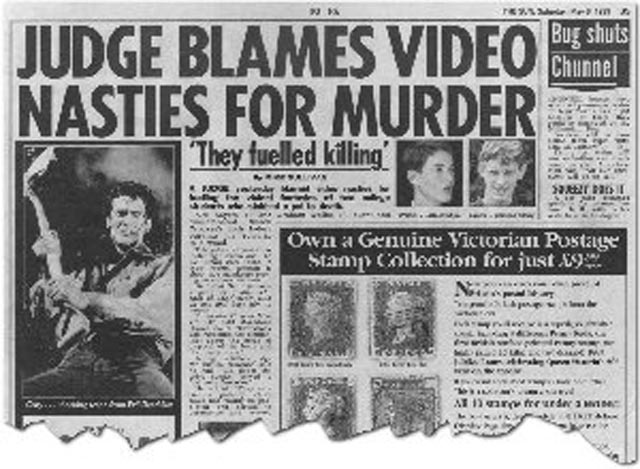

Quite understandably, this new territory could have been minutely intimidating, but the painstakingly long journey that horror went through to gain integration into the mainstream was beyond dramatically treacherous. The nation, bargained by the media, believed that these films were serious enough to be considered a moral panic, meaning that a general feeling of fear was felt across society mainly due to scaremongering and falsely constructed information. The barrage of terror was helmed by the one and only Mary Whitehouse, who for those who may not know is horror’s worst enemy.

Whitehouse alongside the National Viewers and Listeners Association (now Mediawatch-UK) launched the Clean-up TV campaign which garnered over 500,000 signatures. The crusade gained both government and media attention very quickly, resulting in mass vexation. Soon titles such as “How High Street Horror is Invading the Home’‘ (The Sunday Times, 1982) dominated newspapers, with The Daily Mail jumpstarting their own campaign literally called “Ban the Sadist Video”. The most ludicrous statement of them all can be seen in an interview with MP Graham Bright who states that the video nasties will even affect your family pets! Whilst every outlet was busy fabricating how these films were corrupting the youth of Britain, the actual films themselves were basking in the attention, their sales had gone through the roof. Supposedly the saying of ‘all publicity is good publicity’ is true after all.

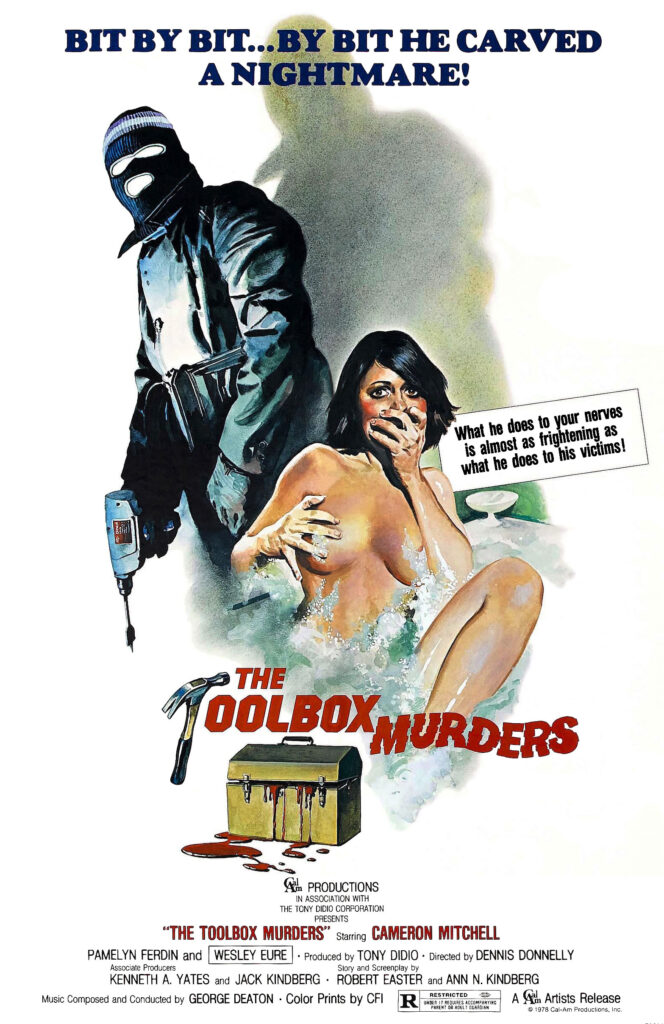

With the hatred was this arrival of attention which made people crave the gore even more. The fantastical cover artwork was purposefully daring, alluring audiences in with the promise of salacious material. Half of the time the covers and titles were far more smutty than the films could ever be. For example, The Toolbox Murders (Dennis Donnelly, 1978) vividly presents a nude woman crouched in front of a masked man wielding a phallically held drill. But the moral campaigners decided to forgo actually watching the content to decipher the actual material, apparently the cover was enough alone to ban this film.

This judgemental notion was truly enforced once Whitehouse, alongside PM Margaret Thatcher, and MP Gareth Wardell had briefly introduced a harsher version of the already implicated Obscene Publication Act 1959 (OPA act), which saw the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) create a list of films that breached the OPA act, the list was modified monthly and at one point featured 72 titles including the now classics Cannibal Holocuast (Ruggero Deodato, 1980), I Spit on Your Grave (Meir Zarchi, 1978), and The Last House on the Left (Wes Craven, 1972). The list proved faulty, but instead of rationalising the seriousness of the ‘issue’ the panic continued to surge, resulting in The Videos Recording Act 1984 (VRA Act) being introduced. From this point on copious films were illegal to sell, with video shops selling such material even facing jail time alongside a hefty fine and license stripping.

With this, the video nasties were officially born. The arrival of the VRA act was damning for future productions, but what truly cast their baptism as dreadful films tainting the scoundrels who dared to watch them was the comedic irony of the whole situation. The papers who blasted the nasties were so strict and constant in their abuse that naturally, the public conformed to what they were being told. In the 1980s there was no social media to get a second opinion, the views were majorly swayed. The moral panic was gradually slowed due to the VRA, with the nasties becoming old news. It wasn’t until years later when these films began to emerge from the pits of darkness (where they supposedly belong), and although horror is home to some pretty grim material some films have still never been released uncut.

The nasties are gone but not forgotten. Villainizing a film is effective to a degree if you are sat on the opposite side, but eventually, the opposition will fall. Brainwashing the public to see the nasties as detrimental undoubtedly worked, yet it is widely known that the peddle pushing did not revolve entirely around the content; the threat of the unknown stayed close within the BBFC’s peripheral, these people were comfortable with their right lifestyle, and the nasties that had injected themselves into Britain’s mainstream were mainly Italian and American produced, showing a whole new set of cultural values. The conformity of the ‘known’ was breaking down, thus forcing traditional British values to be malleable and no longer set in stone. The fear did not solely surround the content of the nasties, but instead the alarm was rung due to the uncharted territory that the films invited in.

Within the current climate, one can view whatever material they wish at the click of a keypad. The iceberg system of disturbing horror would have genuinely caused an entire breakdown across the country if films such as A Serbian Film (Srdjan Spasojevic, 2010) had been released in Britain back then. Even in this day and age, Spasojevic’s exploration into exploitation cinema had major issues with censorship from the BBFC, with multiple cuts being necessary for a release. Audiences are still being tested to this day, many films including A Serbian Film are not overly controversial in comparison to some of horror’s most daring ventures, take for example The Bunny Game (Adam Rehmeier, 2010). Rehmeier is the creator of one of the most harrowing tales legal cinema has ever seen.

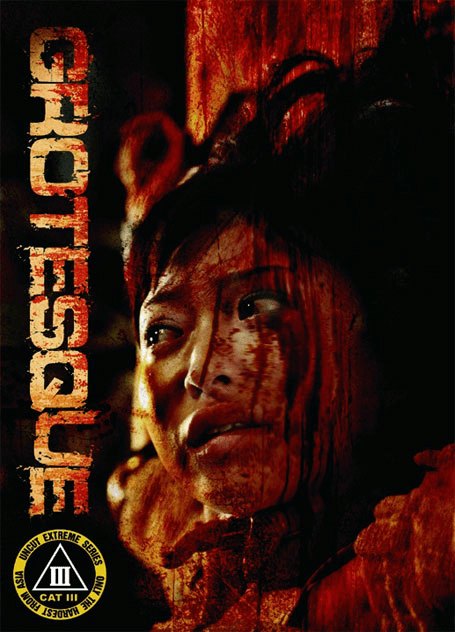

The Bunny Game has been rejected for release in multiple countries including the UK and America, with its strong emphasis on violence against women and unstimulated scenes being too much for censors to handle. Matching this level of violence is Grotesque (Koji Shiraishi, 2009), which gives Takasi Miike’s reputation as Japan’s most controversial director a run for its money. Over time the craving for particularly gruesome horror has soared with many directors battling it out to try and test the boundaries as much as possible.

What can be taken away from the video nasty era is the sense of miscontrol that the genre really has. Although profits have soared and popularity has grown there will always be a stigma against the content. The nasties are a reminder that liberalization within cinema is still a touchy subject.

The days of the nasties seem so long ago, but instead of that section of history being dead and buried it seems that censorship lives on, not necessarily through the BBFC but through public attitudes to the weird and wonderful world of horror.

Late Night with the Devil sees the excellent David Dastmalchian as Jack Delroy, a 1970s

In the world of remakes and sequels, few franchises (if any) have escaped their fair

Believe it or not, it was a whole twenty moons ago that one of the

(Deadline, 2024) Spring’s new psychological horror feature ‘Immaculate’ sees Sydney Sweeney star as Sister Cecelia,